In particle physics, a fermion is a particle that follows Fermi–Dirac statistics. Fermions have a half-odd-integer spin and obey the Pauli exclusion principle. These particles include all quarks and leptons and all composite particles made of an odd number of these, such as all baryons and many atoms and nuclei. Fermions differ from bosons, which obey Bose–Einstein statistics.

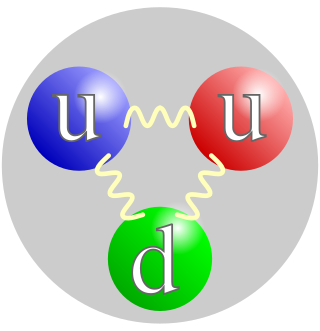

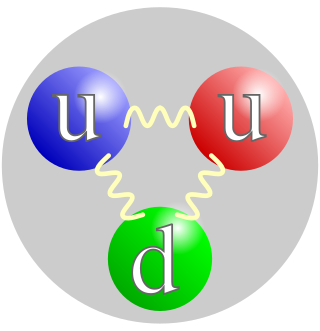

In particle physics, a hadron is a composite subatomic particle made of two or more quarks held together by the strong interaction. They are analogous to molecules, which are held together by the electric force. Most of the mass of ordinary matter comes from two hadrons: the proton and the neutron, while most of the mass of the protons and neutrons is in turn due to the binding energy of their constituent quarks, due to the strong force.

A muon is an elementary particle similar to the electron, with an electric charge of −1 e and a spin of 1/2, but with a much greater mass. It is classified as a lepton. As with other leptons, the muon is not thought to be composed of any simpler particles.

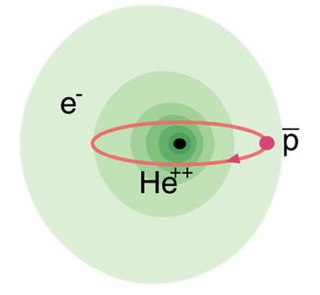

Muonium is an exotic atom made up of an antimuon and an electron, which was discovered in 1960 by Vernon W. Hughes and is given the chemical symbol Mu. During the muon's 2.2 µs lifetime, muonium can undergo chemical reactions. Because, like a proton, the antimuon's mass is vastly larger than that of the electron, muonium is more similar to atomic hydrogen than positronium. Its Bohr radius and ionization energy are within 0.5% of hydrogen, deuterium, and tritium, and thus it can usefully be considered as an exotic light isotope of hydrogen.

Particle physics or high-energy physics is the study of fundamental particles and forces that constitute matter and radiation. The field also studies combinations of elementary particles up to the scale of protons and neutrons, while the study of combination of protons and neutrons is called nuclear physics.

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol

p

, H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 e (elementary charge). Its mass is slightly less than the mass of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton-to-electron mass ratio). Protons and neutrons, each with masses of approximately one atomic mass unit, are jointly referred to as "nucleons" (particles present in atomic nuclei).

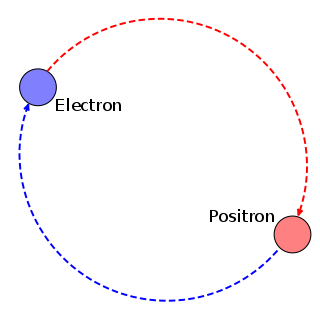

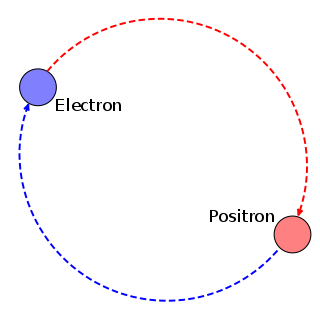

Positronium (Ps) is a system consisting of an electron and its anti-particle, a positron, bound together into an exotic atom, specifically an onium. Unlike hydrogen, the system has no protons. The system is unstable: the two particles annihilate each other to predominantly produce two or three gamma-rays, depending on the relative spin states. The energy levels of the two particles are similar to that of the hydrogen atom. However, because of the reduced mass, the frequencies of the spectral lines are less than half of those for the corresponding hydrogen lines.

A timeline of atomic and subatomic physics.

The Bohr radius is a physical constant, approximately equal to the most probable distance between the nucleus and the electron in a hydrogen atom in its ground state. It is named after Niels Bohr, due to its role in the Bohr model of an atom. Its value is 5.29177210544(82)×10−11 m.

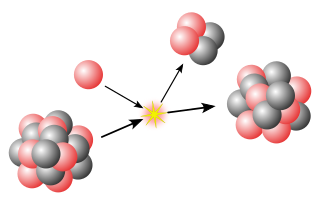

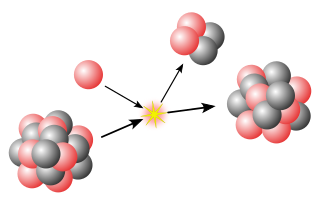

Muon-catalyzed fusion is a process allowing nuclear fusion to take place at temperatures significantly lower than the temperatures required for thermonuclear fusion, even at room temperature or lower. It is one of the few known ways of catalyzing nuclear fusion reactions.

The tau, also called the tau lepton, tau particle, tauon or tau electron, is an elementary particle similar to the electron, with negative electric charge and a spin of 1/2. Like the electron, the muon, and the three neutrinos, the tau is a lepton, and like all elementary particles with half-integer spin, the tau has a corresponding antiparticle of opposite charge but equal mass and spin. In the tau's case, this is the "antitau". Tau particles are denoted by the symbol

τ−

and the antitaus by

τ+

.

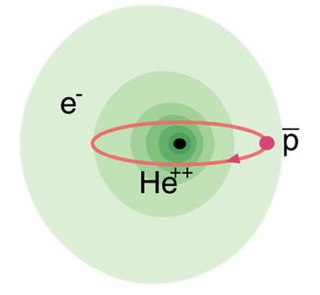

Antiprotonic helium is a three-body atom composed of an antiproton and an electron orbiting around a helium nucleus. It is thus made partly of matter, and partly of antimatter. The atom is electrically neutral, since both electrons and antiprotons each have a charge of −1, whereas helium nuclei have a charge of +2. It has the longest lifetime of any experimentally producible matter-antimatter bound state.

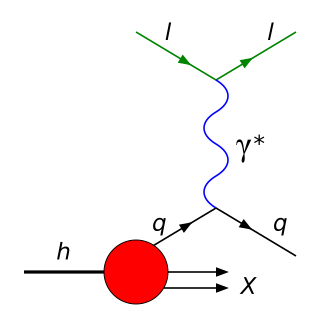

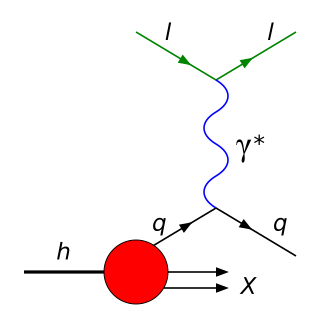

In particle physics, deep inelastic scattering is the name given to a process used to probe the insides of hadrons, using electrons, muons and neutrinos. It was first attempted in the 1960s and 1970s and provided the first convincing evidence of the reality of quarks, which up until that point had been considered by many to be a purely mathematical phenomenon. It is an extension of Rutherford scattering to much higher energies of the scattering particle and thus to much finer resolution of the components of the nuclei.

In quantum electrodynamics, the anomalous magnetic moment of a particle is a contribution of effects of quantum mechanics, expressed by Feynman diagrams with loops, to the magnetic moment of that particle. The magnetic moment, also called magnetic dipole moment, is a measure of the strength of a magnetic source.

Nuclear binding energy in experimental physics is the minimum energy that is required to disassemble the nucleus of an atom into its constituent protons and neutrons, known collectively as nucleons. The binding energy for stable nuclei is always a positive number, as the nucleus must gain energy for the nucleons to move apart from each other. Nucleons are attracted to each other by the strong nuclear force. In theoretical nuclear physics, the nuclear binding energy is considered a negative number. In this context it represents the energy of the nucleus relative to the energy of the constituent nucleons when they are infinitely far apart. Both the experimental and theoretical views are equivalent, with slightly different emphasis on what the binding energy means.

Quantum electrodynamics (QED), a relativistic quantum field theory of electrodynamics, is among the most stringently tested theories in physics. The most precise and specific tests of QED consist of measurements of the electromagnetic fine-structure constant, α, in various physical systems. Checking the consistency of such measurements tests the theory.

An onium is a bound state of a particle and its antiparticle. These states are usually named by adding the suffix -onium to the name of one of the constituent particles, with one exception for "muonium"; a muon–antimuon bound pair is called "true muonium" to avoid confusion with old nomenclature.

The atomic nucleus is the small, dense region consisting of protons and neutrons at the center of an atom, discovered in 1911 by Ernest Rutherford based on the 1909 Geiger–Marsden gold foil experiment. After the discovery of the neutron in 1932, models for a nucleus composed of protons and neutrons were quickly developed by Dmitri Ivanenko and Werner Heisenberg. An atom is composed of a positively charged nucleus, with a cloud of negatively charged electrons surrounding it, bound together by electrostatic force. Almost all of the mass of an atom is located in the nucleus, with a very small contribution from the electron cloud. Protons and neutrons are bound together to form a nucleus by the nuclear force.

For atoms where muons have replaced one or more electrons, see Muonic atom. For the onium of an electron and an antimuon, see muonium.