Related Research Articles

Fear is an emotion induced by perceived danger or threat, which causes physiological changes and ultimately behavioral changes, such as fleeing, hiding, or freezing from perceived traumatic events. Fear in human beings may occur in response to a certain stimulus occurring in the present, or in anticipation or expectation of a future threat perceived as a risk to oneself. The fear response arises from the perception of danger leading to confrontation with or escape from/avoiding the threat, which in extreme cases of fear can be a freeze response or paralysis.

A phobia is a type of anxiety disorder defined by a persistent and excessive fear of an object or situation. Phobias typically result in a rapid onset of fear and are present for more than six months. Those affected will go to great lengths to avoid the situation or object, to a degree greater than the actual danger posed. If the object or situation cannot be avoided, they experience significant distress. Other symptoms can include fainting, which may occur in blood or injury phobia, and panic attacks, which are often found in agoraphobia. Around 75% of those with phobias have multiple phobias.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental disorder that can develop after a person is exposed to a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, or other threats on a person's life. Symptoms may include disturbing thoughts, feelings, or dreams related to the events, mental or physical distress to trauma-related cues, attempts to avoid trauma-related cues, alterations in how a person thinks and feels, and an increase in the fight-or-flight response. These symptoms last for more than a month after the event. Young children are less likely to show distress, but instead may express their memories through play. A person with PTSD is at a higher risk of suicide and intentional self-harm.

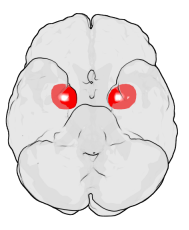

The amygdala is one of two almond-shaped clusters of nuclei located deep and medially within the temporal lobes of the brain in complex vertebrates, including humans. Shown to perform a primary role in the processing of memory, decision-making and emotional responses, the amygdalae are considered part of the limbic system. The term amygdala was first introduced by Karl Friedrich Burdach in 1822.

Classical conditioning refers to a learning procedure in which a biologically potent stimulus is paired with a previously neutral stimulus. It also refers to the learning process that results from this pairing, through which the neutral stimulus comes to elicit a response that is usually similar to the one elicited by the potent stimulus. It was first studied by Ivan Pavlov in 1897.

Pavlovian fear conditioning is a behavioral paradigm in which organisms learn to predict aversive events. It is a form of learning in which an aversive stimulus is associated with a particular neutral context or neutral stimulus, resulting in the expression of fear responses to the originally neutral stimulus or context. This can be done by pairing the neutral stimulus with an aversive stimulus. Eventually, the neutral stimulus alone can elicit the state of fear. In the vocabulary of classical conditioning, the neutral stimulus or context is the "conditional stimulus" (CS), the aversive stimulus is the "unconditional stimulus" (US), and the fear is the "conditional response" (CR).

Acute stress disorder is a psychological response to a terrifying, traumatic, or surprising experience. Acute stress disorder is not fatal, but it may bring about delayed stress reactions if not correctly addressed.

In animals, including humans, the startle response is a largely unconscious defensive response to sudden or threatening stimuli, such as sudden noise or sharp movement, and is associated with negative affect. Usually the onset of the startle response is a startle reflex reaction. The startle reflex is a brainstem reflectory reaction (reflex) that serves to protect vulnerable parts, such as the back of the neck and the eyes (eyeblink) and facilitates escape from sudden stimuli. It is found across the lifespan of many species. A variety of responses may occur because of individual's emotional state, body posture, preparation for execution of a motor task, or other activities. The startle response is implicated in the formation of specific phobias.

Affective neuroscience is the study of the neural mechanisms of emotion. This interdisciplinary field combines neuroscience with the psychological study of personality, emotion, and mood. The putative existence of 'basic emotions' and their defining attributes represents a long lasting and yet unsettled issue in psychology.

Extinction is a behavioral phenomenon observed in both operantly conditioned and classically conditioned behavior, which manifests itself by fading of non-reinforced conditioned response over time. When operant behavior that has been previously reinforced no longer produces reinforcing consequences the behavior gradually stops occurring. In classical conditioning, when a conditioned stimulus is presented alone, so that it no longer predicts the coming of the unconditioned stimulus, conditioned responding gradually stops. For example, after Pavlov's dog was conditioned to salivate at the sound of a metronome, it eventually stopped salivating to the metronome after the metronome had been sounded repeatedly but no food came. Many anxiety disorders such as post traumatic stress disorder are believed to reflect, at least in part, a failure to extinguish conditioned fear.

Reduced affect display, sometimes referred to as emotional blunting, is a condition of reduced emotional reactivity in an individual. It manifests as a failure to express feelings either verbally or nonverbally, especially when talking about issues that would normally be expected to engage the emotions. Expressive gestures are rare and there is little animation in facial expression or vocal inflection. Reduced affect can be symptomatic of autism, schizophrenia, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, depersonalization disorder, schizoid personality disorder or brain damage. It may also be a side effect of certain medications.

Exposure therapy is a technique in behavior therapy to treat anxiety disorders. Exposure therapy involves exposing the target patient to the anxiety source or its context without the intention to cause any danger. Doing so is thought to help them overcome their anxiety or distress. Procedurally, it is similar to the fear extinction paradigm developed studying laboratory rodents. Numerous studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in the treatment of disorders such as generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, PTSD, and specific phobias.

Memory is described by psychology as the ability of an organism to store, retain, and subsequently retrieve information. When an individual experiences a traumatic event, whether physical or psychological, their memory can be affected in many ways. For example, trauma might affect their memory for that event, memory of previous or subsequent events, or thoughts in general.

Incident stress is a condition caused by acute stress which overwhelms a staff person trained to deal with critical incidents such as within the line of duty for first responders, EMTs, and other similar personnel. If not recognized and treated at onset, incident stress can lead to more serious effects of posttraumatic stress disorder.

The management of traumatic memories is important when treating mental health disorders such as post traumatic stress disorder. Traumatic memories can cause life problems even to individuals who do not meet the diagnostic criteria for a mental health disorder. They result from traumatic experiences, including natural disasters such as earthquakes and tsunamis; violent events such as kidnapping, terrorist attacks, war, domestic abuse and rape. Traumatic memories are naturally stressful in nature and emotionally overwhelm people's existing coping mechanisms.

The effects of stress on memory include interference with a person's capacity to encode memory and the ability to retrieve information. During times of stress, the body reacts by secreting stress hormones into the bloodstream. Stress can cause acute and chronic changes in certain brain areas which can cause long-term damage. Over-secretion of stress hormones most frequently impairs long-term delayed recall memory, but can enhance short-term, immediate recall memory. This enhancement is particularly relative in emotional memory. In particular, the hippocampus, prefrontal cortex and the amygdala are affected. One class of stress hormone responsible for negatively affecting long-term, delayed recall memory is the glucocorticoids (GCs), the most notable of which is cortisol. Glucocorticoids facilitate and impair the actions of stress in the brain memory process. Cortisol is a known biomarker for stress. Under normal circumstances, the hippocampus regulates the production of cortisol through negative feedback because it has many receptors that are sensitive to these stress hormones. However, an excess of cortisol can impair the ability of the hippocampus to both encode and recall memories. These stress hormones are also hindering the hippocampus from receiving enough energy by diverting glucose levels to surrounding muscles.

Psychic numbing is a tendency for individuals or societies to withdraw attention from past experiences that were traumatic, or from future threats that are perceived to have massive consequences but low probability. Psychic numbing can be a response to threats as diverse as financial and economic collapse, the risk of nuclear weapon detonations, pandemics, and global warming. It is also important to consider the neuroscience behind the phenomenon, which gives validation to the observable human behavior. The term has evolved to include both societies as well as individuals, so psychic numbing can be viewed from either a collectivist or an individualist standpoint. Individualist psychic numbing is found in victims of rape and people who suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder.

Many experiments have been done to find out how the brain interprets stimuli and how animals develop fear responses. The emotion, fear, has been hard-wired into almost every individual, due to its vital role in the survival of the individual. Researchers have found that fear is established unconsciously and that the amygdala is involved with fear conditioning.

Emotion perception refers to the capacities and abilities of recognizing and identifying emotions in others, in addition to biological and physiological processes involved. Emotions are typically viewed as having three components: subjective experience, physical changes, and cognitive appraisal; emotion perception is the ability to make accurate decisions about another's subjective experience by interpreting their physical changes through sensory systems responsible for converting these observed changes into mental representations. The ability to perceive emotion is believed to be both innate and subject to environmental influence and is also a critical component in social interactions. How emotion is experienced and interpreted depends on how it is perceived. Likewise, how emotion is perceived is dependent on past experiences and interpretations. Emotion can be accurately perceived in humans. Emotions can be perceived visually, audibly, through smell and also through bodily sensations and this process is believed to be different from the perception of non-emotional material.

The potential Genetic influences of post-traumatic stress disorder are ill understood due to the limitations of any genetic study of mental illness; in that it cannot be ethically induced in selected groups. So all studies must use naturally occurring groups with genetic similarities and difference, thus the amount of data is limited. However, Genetics play some role in the development of PTSD. Approximately 30% of the variance in PTSD is caused from genetics alone. For twin pairs exposed to combat in Vietnam, having a monozygotic (identical) twin with PTSD was associated with an increased risk of the co-twin's having PTSD compared to twins that were dizygotic.

References

- ↑ Grillon, C. & Davis, M. (1997). "Fear-potentiated startle conditioning in humans: Explicit and contextual cue conditioning following paired versus unpaired training". Psychophysiology. 34 (4): 451–458. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8986.1997.tb02389.x. PMID 9260498.

- 1 2 Davis, M.; Falls, W. A.; Campeau, S. & Kim, M. (1993). "Fear-Potentiated Startle: A Neural and Pharmacological Analysis". Behavioural Brain Research. 58 (1–2): 175–198. doi:10.1016/0166-4328(93)90102-v. PMID 8136044.

- ↑ Lissek, S.; Biggs, A. L.; Rabin, S. J.; Cornwell, B. R.; Alvarez, R. P.; Pine, D. S. & Grillon, C. (2008). "Generalization of Conditioned Fear-Potentiated Startle in Humans: Experimental Validation and Clinical Relevance". Behaviour Research and Therapy. 46 (5): 678–687. doi:10.1016/j.brat.2008.02.005. PMC 2435484 . PMID 18394587.

- 1 2 Lang, P. J.; Davis, M. & Ohman, A. (2000). "Fear and Anxiety: Animal Models and Human Cognitive Psychophysiology". Journal of Affective Disorders. 61 (3): 137–159. doi:10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00343-8. PMID 11163418.

- 1 2 3 4 Vaidyanathan, U.; Patrick, C. J. & Cuthbert, B. N. (2009). "Linking Dimensional Models of Internalizing Psychopathology to Neurobiological Systems: Affect-Modulated Startle as an Indicator of Fear and Distress Disorders and Affiliated Traits". Psychological Bulletin. 135 (6): 909–942. doi:10.1037/a0017222. PMC 2776729 . PMID 19883142.

- ↑ Grillon, C. (2008). "Models and Mechanisms of Anxiety: Evidence From Startle Studies". Psychopharmacology. 199 (3): 421–437. doi:10.1007/s00213-007-1019-1. PMC 2711770 . PMID 18058089.

- ↑ Bremner, J. D.; Vermetten, E.; Schmahl, C.; Vaccarino, V.; Vythilingam, M.; Afzal, N.; Grillon, C. & Charney, D. S. (2005). "Positron Emission Tomographic Imaging of Neural Correlates of a Fear Acquisition and Extinction Paradigm in Women With Childhood Sexual-Abuse-Related Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder". Psychological Medicine. 35 (6): 791–806. doi:10.1017/s0033291704003290. PMC 3233760 . PMID 15997600.

- ↑ Blumenthal, T. D.; Cuthbert, B. N.; Filion, D. L.; Hackley, S.; Lipp, O. V. & Van Boxtel, A. (2005). "Committee report: Guidelines for Human Startle Eyeblink Electromyographic Studies". Psychophysiology. 42 (1): 1–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00271.x . PMID 15720576.

- ↑ Filion, D. L.; Dawson, M. E. & Schell, A. M. (1998). "The Psychological Significance of Human Startle Eyeblink Modification: A Review". Biological Psychology. 47 (1): 1–43. doi:10.1016/s0301-0511(97)00020-3. PMID 9505132.

- ↑ Pole, N.; Neylan, T. C.; Best, S. R.; Orr, S. P. & Marmar, C. R. (2003). "Fear-Potentiated Startle and Posttraumatic Stress Symptoms in Urban Police Officers". Journal of Traumatic Stress . 16 (5): 471–479. doi:10.1023/a:1025758411370.

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- 1 2 Jovanovic, T.; Norrholm, S. D.; Blanding, N. Q.; Phifer, J. E.; Weiss, T.; Davis, M.; Duncan, E.; Bradley, B. & Ressler, K. (2010). "Fear Potentiation is Associated With Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis Function in PTSD". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 35 (6): 846–857. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.11.009. PMC 2875386 . PMID 20036466.

- ↑ Grillon, C. & Morgan, C. A. (1999). "Fear-Potentiated Startle Conditioning to Explicit and Contextual Cues in Gulf War Veterans With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 108: 134–142. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.108.1.134.

- ↑ Jovanovic, T.; Norrholm, S. D.; Fennell, J. E.; Keyes, M.; Fiallos, A. M.; Myers, K. M.; Davis, M. & Duncan, E. J. (2009). "Posttraumatic Stress Disorder May Be Associated With Impaired Fear Inhibition: Relation to Symptom Severity". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 167 (1–2): 151–160. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2007.12.014. PMC 2713500 . PMID 19345420.

- ↑ Milad, M. R.; Orr, S. P.; Lasko, N. B.; Chang, Y.; Rauch, S. L. & Pitman, R. K. (2008). "Presence and Acquired Origin of Reduced Recall for Fear Extinction in PTSD: Results of a Twin Study". Journal of Psychiatric Research. 42 (7): 515–520. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychires.2008.01.017. PMC 2377011 . PMID 18313695.