Related Research Articles

A trade union or labor union, often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers whose purpose is to maintain or improve the conditions of their employment, such as attaining better wages and benefits, improving working conditions, improving safety standards, establishing complaint procedures, developing rules governing status of employees and protecting and increasing the bargaining power of workers.

Labour economics, or labor economics, seeks to understand the functioning and dynamics of the markets for wage labour. Labour is a commodity that is supplied by labourers, usually in exchange for a wage paid by demanding firms. Because these labourers exist as parts of a social, institutional, or political system, labour economics must also account for social, cultural and political variables.

Labour laws, labour code or employment laws are those that mediate the relationship between workers, employing entities, trade unions, and the government. Collective labour law relates to the tripartite relationship between employee, employer, and union.

A minimum wage is the lowest remuneration that employers can legally pay their employees—the price floor below which employees may not sell their labor. Most countries had introduced minimum wage legislation by the end of the 20th century. Because minimum wages increase the cost of labor, companies often try to avoid minimum wage laws by using gig workers, by moving labor to locations with lower or nonexistent minimum wages, or by automating job functions. Minimum wage policies can vary significantly between countries or even within a country, with different regions, sectors, or age groups having their own minimum wage rates. These variations are often influenced by factors such as the cost of living, regional economic conditions, and industry-specific factors.

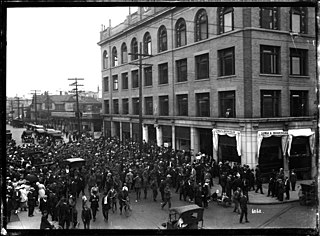

Strike action, also called labor strike, labour strike and industrial action in British English, or simply strike, is a work stoppage caused by the mass refusal of employees to work. A strike usually takes place in response to employee grievances. Strikes became common during the Industrial Revolution, when mass labor became important in factories and mines. As striking became a more common practice, governments were often pushed to act. When government intervention occurred, it was rarely neutral or amicable. Early strikes were often deemed unlawful conspiracies or anti-competitive cartel action and many were subject to massive legal repression by state police, federal military power, and federal courts. Many Western nations legalized striking under certain conditions in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Industrial relations or employment relations is the multidisciplinary academic field that studies the employment relationship; that is, the complex interrelations between employers and employees, labor/trade unions, employer organizations, and the state.

Collective bargaining is a process of negotiation between employers and a group of employees aimed at agreements to regulate working salaries, working conditions, benefits, and other aspects of workers' compensation and rights for workers. The interests of the employees are commonly presented by representatives of a trade union to which the employees belong. A collective agreement reached by these negotiations functions as a labour contract between an employer and one or more unions, and typically establishes terms regarding wage scales, working hours, training, health and safety, overtime, grievance mechanisms, and rights to participate in workplace or company affairs. Such agreements can also include 'productivity bargaining' in which workers agree to changes to working practices in return for higher pay or greater job security.

Employment is a relationship between two parties regulating the provision of paid labour services. Usually based on a contract, one party, the employer, which might be a corporation, a not-for-profit organization, a co-operative, or any other entity, pays the other, the employee, in return for carrying out assigned work. Employees work in return for wages, which can be paid on the basis of an hourly rate, by piecework or an annual salary, depending on the type of work an employee does, the prevailing conditions of the sector and the bargaining power between the parties. Employees in some sectors may receive gratuities, bonus payments or stock options. In some types of employment, employees may receive benefits in addition to payment. Benefits may include health insurance, housing, disability insurance. Employment is typically governed by employment laws, organisation or legal contracts.

A living wage is defined as the minimum income necessary for a worker to meet their basic needs. This is not the same as a subsistence wage, which refers to a biological minimum, or a solidarity wage, which refers to a minimum wage tracking labor productivity. Needs are defined to include food, housing, and other essential needs such as clothing. The goal of a living wage is to allow a worker to afford a basic but decent standard of living through employment without government subsidies. Due to the flexible nature of the term "needs", there is not one universally accepted measure of what a living wage is and as such it varies by location and household type. A related concept is that of a family wage – one sufficient to not only support oneself, but also to raise a family.

The term efficiency wages was introduced by Alfred Marshall to denote the wage per efficiency unit of labor. Marshallian efficiency wages are those calculated with efficiency or ability exerted being the unit of measure rather than time. That is, the more efficient worker will be paid more than a less efficient worker for the same amount of hours worked.

United States labor law sets the rights and duties for employees, labor unions, and employers in the US. Labor law's basic aim is to remedy the "inequality of bargaining power" between employees and employers, especially employers "organized in the corporate or other forms of ownership association". Over the 20th century, federal law created minimum social and economic rights, and encouraged state laws to go beyond the minimum to favor employees. The Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 requires a federal minimum wage, currently $7.25 but higher in 29 states and D.C., and discourages working weeks over 40 hours through time-and-a-half overtime pay. There are no federal laws, and few state laws, requiring paid holidays or paid family leave. The Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993 creates a limited right to 12 weeks of unpaid leave in larger employers. There is no automatic right to an occupational pension beyond federally guaranteed Social Security, but the Employee Retirement Income Security Act of 1974 requires standards of prudent management and good governance if employers agree to provide pensions, health plans or other benefits. The Occupational Safety and Health Act of 1970 requires employees have a safe system of work.

Labor rights or workers' rights are both legal rights and human rights relating to labor relations between workers and employers. These rights are codified in national and international labor and employment law. In general, these rights influence working conditions in the relations of employment. One of the most prominent is the right to freedom of association, otherwise known as the right to organize. Workers organized in trade unions exercise the right to collective bargaining to improve working conditions.

The degree of labour market flexibility is the speed with which labour markets adapt to fluctuations and changes in society, the economy or production. This entails enabling labour markets to reach a continuous equilibrium determined by the intersection of the demand and supply curves.

Labor relations or labor studies is a field of study that can have different meanings depending on the context in which it is used. In an international context, it is a subfield of labor history that studies the human relations with regard to work in its broadest sense and how this connects to questions of social inequality. It explicitly encompasses unregulated, historical, and non-Western forms of labor. Here, labor relations define "for or with whom one works and under what rules. These rules determine the type of work, type and amount of remuneration, working hours, degrees of physical and psychological strain, as well as the degree of freedom and autonomy associated with the work." More specifically in a North American and strictly modern context, labor relations is the study and practice of managing unionized employment situations. In academia, labor relations is frequently a sub-area within industrial relations, though scholars from many disciplines including economics, sociology, history, law, and political science also study labor unions and labor movements. In practice, labor relations is frequently a subarea within human resource management. Courses in labor relations typically cover labor history, labor law, union organizing, bargaining, contract administration, and important contemporary topics.

A collective agreement, collective labour agreement (CLA) or collective bargaining agreement (CBA) is a written contract negotiated through collective bargaining for employees by one or more trade unions with the management of a company that regulates the terms and conditions of employees at work. This includes regulating the wages, benefits, and duties of the employees and the duties and responsibilities of the employer or employers and often includes rules for a dispute resolution process.

Labour in India refers to employment in the economy of India. In 2020, there were around 476.67 million workers in India, the second largest after China. Out of which, agriculture industry consist of 41.19%, industry sector consist of 26.18% and service sector consist 32.33% of total labour force. Of these over 94 percent work in unincorporated, unorganised enterprises ranging from pushcart vendors to home-based diamond and gem polishing operations. The organised sector includes workers employed by the government, state-owned enterprises and private sector enterprises. In 2008, the organised sector employed 27.5 million workers, of which 17.3 million worked for government or government owned entities.

A whipsaw strike is a strike by a trade union against only one or a few employers in an industry or a multi-employer association at a time. The strike is often of a short duration, and usually recurs during the labor dispute or contract negotiations—hence the name "whipsaw".

In economics, a monopsony is a market structure in which a single buyer substantially controls the market as the major purchaser of goods and services offered by many would-be sellers. The microeconomic theory of monopsony assumes a single entity to have market power over all sellers as the only purchaser of a good or service. This is a similar power to that of a monopolist, which can influence the price for its buyers in a monopoly, where multiple buyers have only one seller of a good or service available to purchase from.

The Labor policy in the Philippines is specified mainly by the country's Labor Code of the Philippines and through other labor laws. They cover 38 million Filipinos who belong to the labor force and to some extent, as well as overseas workers. They aim to address Filipino workers’ legal rights and their limitations with regard to the hiring process, working conditions, benefits, policymaking on labor within the company, activities, and relations with employees.

Alan Manning is a British economist and professor of economics at the London School of Economics.

References

- ↑ The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy, 3rd ed., edited by E.D. Hirsch Jr., Joseph F. Kett, and James Trefil, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2002. ISBN 0-618-22647-8

- 1 2 William Gomberg, "Featherbedding: An Assertion of Property Rights," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 333:1 (1961).

- ↑ "Featherbedding Brass," Time, May 14, 1956; C.A. Myers, "Top Management Featherbedding?", Sloan Management Review, 24:4 (1983).

- ↑ Jarita Duasa and Paul Mosley, "Capital Controls Re-examined: The Case for 'Smart' Controls," The World Economy, 29:9 (September 2006).

- ↑ Merriam-Webster's Dictionary of Law, 1st ed., Merriam-Webster, Inc., 1996. ISBN 0-87779-604-1

- ↑ Featherbedding on the Railroads: by Law and by Agreement

- 1 2 Norman J. Simler, "The Economics of Featherbedding", in Featherbedding and Technological Change, ed. by Paul Weinstein, D.C. Heath and Co., 1965.

- ↑ American Newspaper Publishers Association v. National Labor Relations Board, 345 U.S. 100 (1953).

- 1 2 Paul A. Weinstein, "The Featherbedding Problem," American Economic Review, 54:3 (May, 1964).

- ↑ Adam Seth Litwin, "Not featherbedding, but feathering the nest: Human resource management and investments in information technology." Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society 52.1 (2013): 23. "However, from a labor economist’s perspective, employment relations structures and processes were simply spreading the cost associated with technological change by constraining the degree to and the speed with which capital-labor ratios could be adjusted."

- ↑ Lloyd Ulman, The Rise of the National Trade Union, Harvard University Press, 1955; Clarence C. Morrison and Herbert J. Kiesling, "Featherbedding—An Easy Second Best Problem," Atlantic Economic Journal, 4:3 (September 1976).

- ↑ Henry S. Farber, "The analysis of union behavior," Handbook of labor economics 2 (1986): 1039–89.

- ↑ George E. Johnson, "Work Rules, Featherbedding, and Pareto-Optimal Union Management Bargaining," Journal of Labor Economics, 8:1 (Part 2, 1990).

- ↑ Donald L. Martin, "Job Property Rights and Job Defections," Journal of Law and Economics, 15:2 (October 1972); P.J. White, "Unfair Dismissal Legislation and Property Rights: Some Reflections," Industrial Relations Journal, 16:4 (December 1985); Ellen Dannin, "Why At-Will Employment Is Bad For Employers and Just Cause Is Good For Them," Labor Law Journal, 58:5 (2007).

- ↑ Werner Sengenberger, The Role of Labour Standards in Industrial Restructuring: Participation, Protection and Promotion, International Institute for Labour Studies, International Labour Organization, 1990. ISBN 92-9014-482-3

- ↑ Charles Perrow, Complex Organizations: A Critical Essay, Scott, Foresman & Co., 1979. ISBN 0-673-15205-7

- ↑ Evert Reerink, "Defining Quality of Care: Mission Impossible?", International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 2 (1990); Rick L. Nevers, "Defining Quality Is Difficult, But Necessary," Healthcare Financial Management, February 1993; Philip Caper, "Defining Quality in Medical Care," Health Affairs, Spring 1988.

- ↑ Hans F. Crombag, "On Defining Quality of Education," Journal Higher Education, 7:4 (November 1978); Alisa Belzer, ed., Toward Defining and Improving Quality in Adult Basic Education: Issues and Challenges, 1st ed., Lawrence Erlbaum, 2007. ISBN 0-8058-5545-9; Eric A. Hanushek, John F. Kain, Daniel M. O'Brien, and Steven G. Rivkin, The Market for Teacher Quality, NBER Working Paper No. 11154, National Bureau of Economic Research, August 2005; Dan Goldhaber and Emily Anthony, Can Teacher Quality be Effectively Assessed?", The Urban Institute, April 2004; Jeannie Oakes, Megan Loef Franke, Karen Hunter Quartz, and John Rogers, "Research for High-Quality Urban Teaching: Defining It, Developing It, Assessing It," Journal of Teacher Education, 53:3 (2002).

- ↑ "Nurses and hospitals are increasingly agreeing that various departments have a minimum number of nurses, and teachers' contracts are specifying maximum class sizes, in effect guaranteeing that school districts have a minimum number of teachers for the student population." Steven Greenhouse, "Big Audience Guaranteed For This Labor Dispute," New York Times, March 9, 2003.

- ↑ Virginia Cleland, "The Professional Model," American Journal of Nursing, 75:2 (February 1975); David Lewin and Bruce Kaufman, eds., New Research on Labor Relations and the Performance of University HR/IR Programs, 1st ed., JAI Press, 2000. ISBN 0-7623-0750-1

- ↑ Jess B. Weiss, "Perspectives: An Anesthesiologist," Health Affairs, Fall 1988.

- ↑ M. Delal Baer, "Profiles in Transition in Latin America and the Caribbean," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 526 (March 1993); William F. Maloney, "Informality Revisited," World Development, 32:7 (July 2004).

- ↑ De Gramont, Sanche, The French, Portrait of a People, G. P. Putman's Sons, New York, 1969, p. 440

- ↑ Thomas J. DiLorenzo, "Japanese Labor Relations: Are There Lessons for the U.S.?", Journal of Labor Research, 11:3 (September, 1990).

- ↑ Reinhold Fahlbeck, Trade Unionism in Sweden, International Institute for Labour Studies, International Labour Organization, 1999. ISBN 92-9014-617-6

- ↑ George E. Johnson, "Work Rules, Featherbedding, and Pareto-Optimal Union-Management Bargaining," Journal of Labor Economics, 8:1 (Part 2; January 1990).

- ↑ "Featherbedding and Taft-Hartley," Columbia Law Review, 52:8 (December 1952).