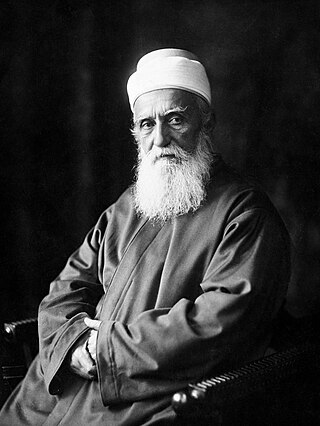

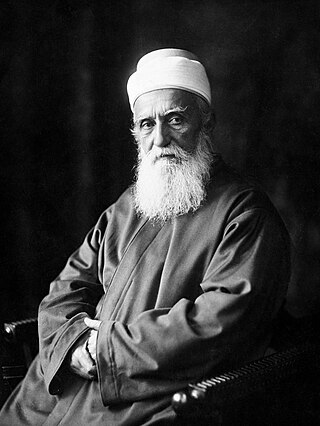

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, born ʻAbbás, was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh and served as head of the Baháʼí Faith from 1892 until 1921. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was later canonized as the last of three "central figures" of the religion, along with Baháʼu'lláh and the Báb, and his writings and authenticated talks are regarded as sources of Baháʼí sacred literature.

The Baháʼí Faith is a religion founded in the 19th century that teaches the essential worth of all religions and the unity of all people. Established by Baháʼu'lláh, it initially developed in Qajar Iran and parts of the Middle East, where it has faced ongoing persecution since its inception. The religion is estimated to have 5 to 8 million adherents, known as Baháʼís, spread throughout most of the world's countries and territories.

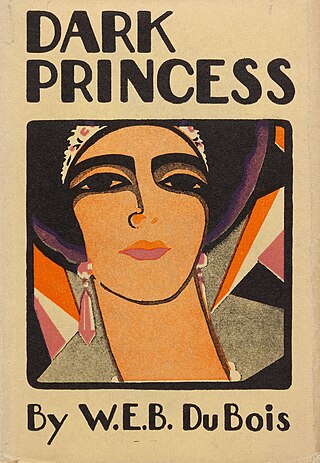

William Edward Burghardt Du Bois was an American sociologist, socialist, historian, and Pan-Africanist civil rights activist.

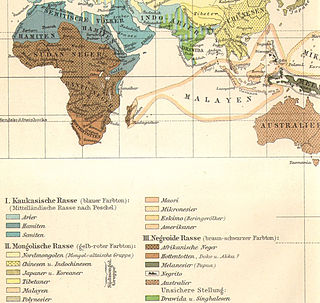

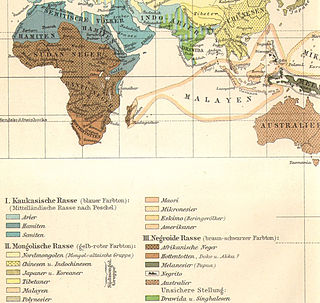

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscientific belief that the human species can be subdivided into biologically distinct taxa called "races", and that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism, racial inferiority, or racial superiority. Before the mid-20th century, scientific racism was accepted throughout the scientific community, but it is no longer considered scientific. The division of humankind into biologically separate groups, along with the assignment of particular physical and mental characteristics to these groups through constructing and applying corresponding explanatory models, is referred to as racialism, race realism, or race science by those who support these ideas. Modern scientific consensus rejects this view as being irreconcilable with modern genetic research.

Carter Godwin Woodson was an American historian, author, journalist, and the founder of the Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH). He was one of the first scholars to study the history of the African diaspora, including African-American history. A founder of The Journal of Negro History in 1916, Woodson has been called the "father of black history." In February 1926, he launched the celebration of "Negro History Week," the precursor of Black History Month. Woodson was an important figure to the movement of Afrocentrism, due to his perspective of placing people of African descent at the center of the study of history and the human experience.

The Baháʼí teachings represent a considerable number of theological, ethical, social, and spiritual ideas that were established in the Baháʼí Faith by Baháʼu'lláh, the founder of the religion, and clarified by its successive leaders: ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, Baháʼu'lláh's son, and Shoghi Effendi, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's grandson. The teachings were written in various Baháʼí writings. The teachings of the Baháʼí Faith, combined with the authentic teachings of several past religions, are regarded by Baháʼís as revealed by God.

The Baháʼí Faith teaches that the world should adopt an international auxiliary language, which people would use in addition to their mother tongue. The aim of this teaching is to improve communication and foster unity among peoples and nations. The Baháʼí teachings state, however, that the international auxiliary language should not suppress existing natural languages, and that the concept of unity in diversity must be applied to preserve cultural distinctions. The Baha'i principle of an International Auxiliary Language (IAL) represents a paradigm for establishing peaceful and reciprocal relations between the world's primary speech communities – while shielding them from undue linguistic pressures from the dominant speech community/communities.

Unity of humanity is one of the central teachings of the Baháʼí Faith. The Baháʼí teachings state that since all humans have been created in the image of God, God does not make any distinction between people regardless of race or colour. Thus, because all humans have been created equal, they all require equal opportunities and treatment. Thus the Baháʼí view promotes the unity of humanity, and that people's vision should be world-embracing and that people should love the whole world rather than just their nation. The teaching, however, does not equate unity with uniformity, but instead the Baháʼí writings advocate for the principle of unity in diversity where the variety in the human race is valued.

Louis George Gregory was a prominent American member of the Baháʼí Faith who was devoted to its expansion in the United States and elsewhere. He traveled especially in the South to spread his religion as well as advocating for racial unity.

Alain LeRoy Locke was an American writer, philosopher, and educator. Distinguished in 1907 as the first African-American Rhodes Scholar, Locke became known as the philosophical architect—the acknowledged "Dean"—of the Harlem Renaissance. He is frequently included in listings of influential African Americans. On March 19, 1968, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. proclaimed: "We're going to let our children know that the only philosophers that lived were not Plato and Aristotle, but W. E. B. Du Bois and Alain Locke came through the universe."

Hamites is the name formerly used for some Northern and Horn of Africa peoples in the context of a now-outdated model of dividing humanity into different races; this was developed originally by Europeans in support of colonialism and slavery. The term was originally borrowed from the Book of Genesis, in which it refers to the descendants of Ham, son of Noah.

Negroid is an obsolete racial grouping of various people indigenous to Africa south of the area which stretched from the southern Sahara desert in the west to the African Great Lakes in the southeast, but also to isolated parts of South and Southeast Asia (Negritos). The term is derived from now-disproven conceptions of race as a biological category.

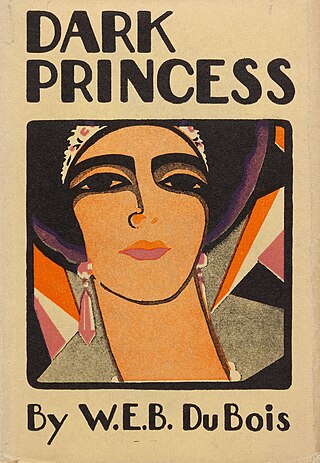

Dark Princess, written by sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois in 1928, is one of his five historical novels. One of Du Bois's favorite works, the novel explores the beauty of people of color around the world. This was part of Du Bois' use of fiction to explore his times in a way not possible in non-fiction history. He expressed fully imagined lives of his characters, using them to explore the richness and beauty of black culture. The novel was not well received when published. It was criticized for its expression of eroticism as well as for what some critics thought was a failed attempt at social realism.

ʻAbdu'l-Bahá's journeys to the West were a series of trips ʻAbdu'l-Bahá undertook starting at the age of 66, journeying continuously from Palestine to the West between 1910 and 1913. ʻAbdu'l-Bahá was the eldest son of Baháʼu'lláh, founder of the Baháʼí Faith, and suffered imprisonment with his father starting at the age of 8; he suffered various degrees of privation for almost 55 years, until the Young Turk Revolution in 1908 freed religious prisoners of the Ottoman Empire. Upon the death of his father in 1892, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá had been appointed as the successor, authorized interpreter of Bahá'u'lláh's teachings, and Center of the Covenant of the Baháʼí Faith.

The sociology of race and ethnic relations is the study of social, political, and economic relations between races and ethnicities at all levels of society. This area encompasses the study of systemic racism, like residential segregation and other complex social processes between different racial and ethnic groups.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to the Baháʼí Faith.

The First Pan-African Conference was held in London from 23 to 25 July 1900. Organized primarily by the Trinidadian barrister Henry Sylvester Williams, the conference took place in Westminster Town Hall and was attended by 37 delegates and about 10 other participants and observers from Africa, the West Indies, the US and the UK, including Samuel Coleridge-Taylor, John Alcindor, Benito Sylvain, Dadabhai Naoroji, John Archer, Henry Francis Downing, Anna H. Jones, Anna Julia Cooper, and W. E. B. Du Bois, with Bishop Alexander Walters of the AME Zion Church taking the chair.

Gustav Spiller was a Hungarian-born ethical and sociological writer who was active in Ethical Societies in the United Kingdom. He helped to organize the First Universal Races Congress in 1911.

The Baháʼí Faith was discussed in the writings of various Western intellectuals and scholars during the lifetime of Baháʼu'lláh. His son and successor, ʻAbdu'l-Bahá, travelled to France and Great Britain and gave talks to audiences there. There is a Baháʼí House of Worship in Langenhain, Germany, which was completed in 1964. The Association of Religion Data Archives reported national Baháʼí populations ranging from hundreds to over 35,000 in 2005. The European Union and several European countries have condemned the persecution of Baháʼís in Iran.

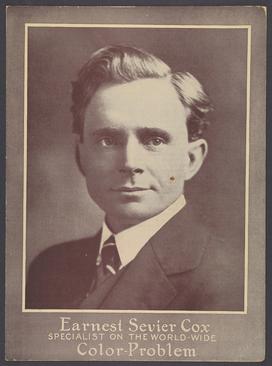

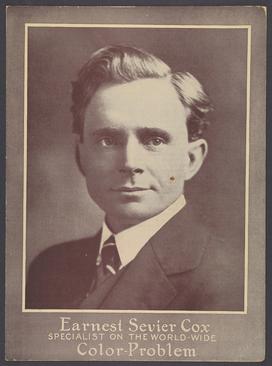

Earnest Sevier Cox was an American Methodist preacher, political activist and white supremacist. He is best known for his political campaigning for stricter segregation between blacks and whites in the United States through tougher anti-miscegenation laws, for his advocacy for "repatriation" of African Americans to Africa, and for his book White America. He is also noted for having mediated collaboration between white southern segregationists and African American separatist organizations such as UNIA and the Peace Movement of Ethiopia to advocate for repatriation legislation, and for having been a personal friend of black racial separatist Marcus Garvey.