Gluten is a structural protein naturally found in certain cereal grains. The term gluten usually refers to a wheat grain's prolamins, specifically glutelin proteins, that naturally occur in many cereal grains, and which can trigger celiac disease in some people. The types of grains that contain gluten include all species of wheat, and barley, rye, and some cultivars of oat; moreover, cross hybrids of any of these cereal grains also contain gluten, e.g. triticale. Gluten makes up 75–85% of the total protein in bread wheat.

Pasta is a type of food typically made from an unleavened dough of wheat flour mixed with water or eggs, and formed into sheets or other shapes, then cooked by boiling or baking. Pasta was traditionally only made with durum, although the definition has been expanded to include alternatives for a gluten-free diet, such as rice flour, or legumes such as beans or lentils. While Asian noodles are believed to have originated in China, pasta is believed to have independently originated in Italy and is a staple food of Italian cuisine, with evidence of Etruscans making pasta as early as 400 BCE in Italy.

Bread is a staple food prepared from a dough of flour and water, usually by baking. Throughout recorded history and around the world, it has been an important part of many cultures' diet. It is one of the oldest human-made foods, having been of significance since the dawn of agriculture, and plays an essential role in both religious rituals and secular culture.

Cornbread is a quick bread made with cornmeal, associated with the cuisine of the Southern United States, with origins in Native American cuisine. It is an example of batter bread. Dumplings and pancakes made with finely ground cornmeal are staple foods of the Hopi people in Arizona. The Hidatsa people of the Upper Midwest call baked cornbread naktsi. Cherokee and Seneca tribes enrich the basic batter, adding chestnuts, sunflower seeds, apples, or berries, and sometimes combine it with beans or potatoes. Modern versions of cornbread are usually leavened by baking powder.

Dough is a thick, malleable, sometimes elastic paste made from grains or from leguminous or chestnut crops. Dough is typically made by mixing flour with a small amount of water or other liquid and sometimes includes yeast or other leavening agents, as well as ingredients such as fats or flavorings.

Soda bread is a variety of quick bread made in many cuisines in which sodium bicarbonate is used as a leavening agent instead of yeast. The basic ingredients of soda bread are flour, baking soda, salt, and buttermilk. The buttermilk contains lactic acid, which reacts with the baking soda to form bubbles of carbon dioxide. Other ingredients can be added, such as butter, egg, raisins, or nuts. Quick breads can be prepared quickly and reliably, without requiring the time and labor needed for kneaded yeast breads.

Wheat flour is a powder made from the grinding of wheat used for human consumption. Wheat varieties are called "soft" or "weak" if gluten content is low, and are called "hard" or "strong" if they have high gluten content. Hard flour, or bread flour, is high in gluten, with 12% to 14% gluten content, and its dough has elastic toughness that holds its shape well once baked. Soft flour is comparatively low in gluten and thus results in a loaf with a finer, crumbly texture. Soft flour is usually divided into cake flour, which is the lowest in gluten, and pastry flour, which has slightly more gluten than cake flour.

Rugbrød is a very common form of rye bread from Denmark. Rugbrød usually resembles a long brown extruded rectangle, no more than 12 cm (4.7 in) high, and 30 to 35 cm long, depending on the bread pan in which it is baked. The basic ingredient is rye flour which will produce a plain or "old-fashioned" bread of uniform, somewhat heavy structure, but the most popular versions today contain whole grains and often other seeds such as sunflower seeds, linseeds or pumpkin seeds. Most Danes eat rugbrød every day.

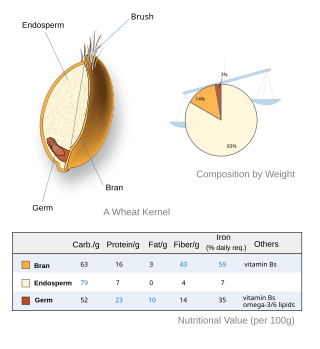

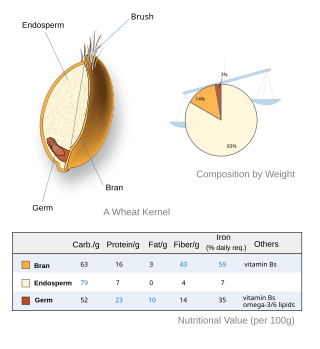

A whole grain is a grain of any cereal and pseudocereal that contains the endosperm, germ, and bran, in contrast to refined grains, which retain only the endosperm.

Rye bread is a type of bread made with various proportions of flour from rye grain. It can be light or dark in color, depending on the type of flour used and the addition of coloring agents, and is typically denser than bread made from wheat flour. Compared to white bread, it is higher in fiber, darker in color, and stronger in flavor. The world's largest exporter of rye bread is Poland.

Lahoh, is a spongy, flat pancake-like bread. It is a type of flat bread eaten regularly in Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia and Yemen. Yemenite Jewish immigrants popularized the dish in Israel. It is called Canjeero/Canjeelo in southern Somalia and Djibouti, and also called Laxoox/Lahoh in northern Somalia, respectively.

Maida, maida flour, or maida mavu is a type of wheat flour originated from the Indian subcontinent. It is a super-refined wheat flour used in Indian cuisine to make pastries and other bakery items like breads and biscuits. Some maida may have tapioca starch added.

Vienna bread is a type of bread that is produced from a process developed in Vienna, Austria, in the 19th century. The Vienna process used high milling of Hungarian grain, and cereal press-yeast for leavening.

Gluten is the seed storage protein in mature wheat seeds. It is the sticky substance in bread wheat which allows dough to rise and retain its shape during baking. The same, or very similar, proteins are also found in related grasses within the tribe Triticeae. Seed glutens of some non-Triticeae plants have similar properties, but none can perform on a par with those of the Triticeae taxa, particularly the Triticum species. What distinguishes bread wheat from these other grass seeds is the quantity of these proteins and the level of subcomponents, with bread wheat having the highest protein content and a complex mixture of proteins derived from three grass species.

A dough conditioner, flour treatment agent, improving agent or bread improver is any ingredient or chemical added to bread dough to strengthen its texture or otherwise improve it in some way. Dough conditioners may include enzymes, yeast nutrients, mineral salts, oxidants and reductants, bleaching agents and emulsifiers. They are food additives combined with flour to improve baking functionality. Flour treatment agents are used to increase the speed of dough rising and to improve the strength and workability of the dough.

Nordic bread culture has existed in Denmark, Finland, Norway, and Sweden from prehistoric times through to the present. It is often characterized by the usage of rye flour, barley flour, a mixture of nuts, seeds, and herbs, and varying densities depending on the region. Often, bread is served as an accompaniment to various recipes and meals. Nordic breads are often seasoned with an assortment of different spices and additives, such as caraway seeds, orange zest, anise, and honey.

In agriculture, grain quality depends on the use of the grain. In ethanol production, the chemical composition of grain such as starch content is important, in food and feed manufacturing, properties such as protein, oil and sugar are significant, in the milling industry, soundness is the most important factor to consider when it comes to the quality of grain. For grain farmers, high germination percentage and seed dormancy are the main features to consider. For consumers, properties such as color and flavor are most important.

Dry milling of grain is mainly utilized to manufacture feedstock into consumer and industrial based products. This process is widely associated with the development of new bio-based associated by-products. The milling process separates the grain into four distinct physical components: the germ, flour, fine grits, and coarse grits. The separated materials are then reduced into food products utilized for human and animal consumption.

Barley flour is a flour prepared from dried and ground barley. Barley flour is used to prepare barley bread and other breads, such as flat bread and yeast breads.

Manitoba flour, a name chiefly used in Italy, is a flour of common wheat originating in the Canadian province of Manitoba. It is a strong flour, and distinguished from weaker flours as measured with a Chopin alveograph.