The Cherokee are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, they were concentrated in their homelands, in towns along river valleys of what is now southwestern North Carolina, southeastern Tennessee, southwestern Virginia, edges of western South Carolina, northern Georgia and northeastern Alabama.

The term Five Civilized Tribes was applied by European Americans in the colonial and early federal period in the history of the United States to the five major Native American nations in the Southeast, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminoles. Americans of European descent classified them as "civilized" because they had adopted attributes of the Anglo-American culture.

The Dawes Rolls were created by the United States Dawes Commission. The commission was authorized by United States Congress in 1893 to execute the General Allotment Act of 1887.

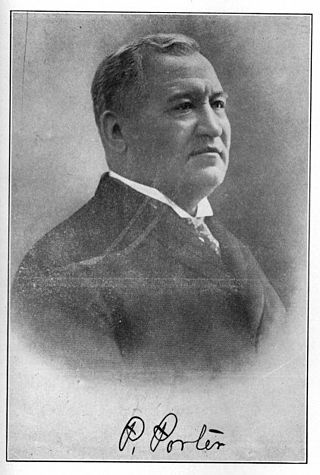

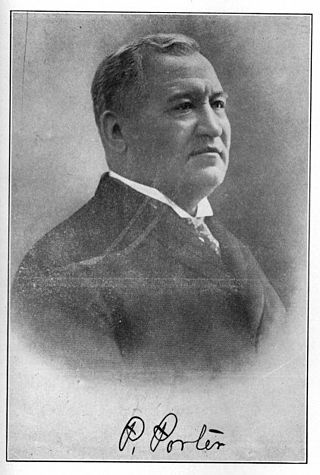

Pleasant Porter, was an American Indian statesman and the last elected Principal Chief of the Creek Nation, serving from 1899 until his death.

The Yuchi people, also spelled Euchee and Uchee, are a Native American tribe based in Oklahoma. Their original homeland was in the southeast of the present United States.

The United Keetoowah Band of Cherokee Indians in Oklahoma is a federally recognized tribe of Cherokee Native Americans headquartered in Tahlequah, Oklahoma. According to the UKB website, its members are mostly descendants of "Old Settlers" or "Western Cherokee," those Cherokee who migrated from the Southeast to present-day Arkansas and Oklahoma around 1817. Some reports estimate that Old Settlers began migrating west by 1800. This was before the forced relocation of Cherokee by the United States in the late 1830s under the Indian Removal Act.

The stomp dance is performed by various Eastern Woodland tribes and Native American communities in the United States, including the Muscogee, Yuchi, Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Delaware, Miami, Caddo, Tuscarora, Ottawa, Quapaw, Peoria, Shawnee, Seminole, Natchez, and Seneca-Cayuga tribes. Stomp dance communities are active in North Carolina, Oklahoma, Alabama, Mississippi, and Florida.

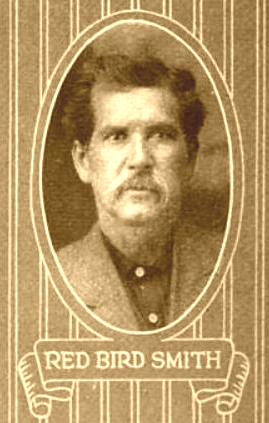

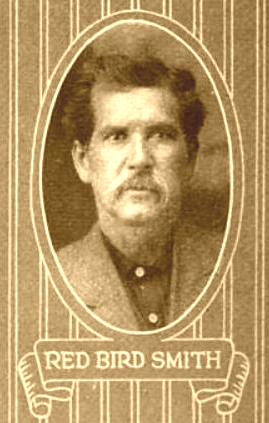

The Keetoowah Nighthawk Society was a Cherokee organisation formed ca. 1900 that intended to preserve and practice traditional "old ways" of tribal life, based on religious nationalism. It was led by Redbird Smith, a Cherokee National Council and original Keetoowah Society member. It formed in the Indian Territory that was superseded by admission of Oklahoma as a state, during the late-nineteenth century period when the federal government was breaking up tribal governments and communal lands under the Dawes Act and Curtis Act. The Nighthawks arose in response to weakening resolve on the part of Cherokee leaders—including the original Keetoowah Society, a political organization created by Cherokee Native American full bloods, in or about 1859—to continue their resistance on behalf of the Cherokee after the Dawes Commission began forcing the transfer of Oklahoma tribal lands in the Indian Territory to individual ownership in the 1890s.

The Original Keetoowah Society is a 21st-century Cherokee religious organization dedicated to preserving the culture and teachings of the Keetoowah Nighthawk Society in Oklahoma. It has been described as the surviving core of the Cherokee movement of religious nationalism originally led by Redbird Smith in the mid-nineteenth century. After the Cherokee were forced to move to Indian Territory, various groups associated with the Keetoowah Society worked to preserve traditional culture and its teachings.

The Curtis Act of 1898 was an amendment to the United States Dawes Act; it resulted in the break-up of tribal governments and communal lands in Indian Territory of the Five Civilized Tribes of Indian Territory: the Choctaw, Chickasaw, Muscogee (Creek), Cherokee, and Seminole. These tribes had been previously exempt from the 1887 General Allotment Act because of the terms of their treaties. In total, the tribes immediately lost control of about 90 million acres of their communal lands; they lost more in subsequent years.

Samuel Houston Mayes of Scots/English-Cherokee descent, was elected as Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory, serving from 1895 to 1899. His maternal grandfather belonged to the Deer clan, and his father was allied with members of the Cherokee Treaty Party in the 1830s, such as the Adair men, Elias Boudinot, and Major Ridge. In the late nineteenth century, his older brother Joel B. Mayes was elected to two terms as Chief of the Cherokee.

The Muscogee Nation, or Muscogee (Creek) Nation, is a federally recognized Native American tribe based in the U.S. state of Oklahoma. The nation descends from the historic Muscogee Confederacy, a large group of indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands. Official languages include Muscogee, Yuchi, Natchez, Alabama, and Koasati, with Muscogee retaining the largest number of speakers. They commonly refer to themselves as Este Mvskokvlke. Historically, they were often referred to by European Americans as one of the Five Civilized Tribes of the American Southeast.

Alexander Lawrence Posey was an American poet, humorist, journalist, and politician in the Creek Nation. He founded the Eufaula Indian Journal in 1901, the first Native American daily newspaper. For several years he published editorial letters known as the Fus Fixico Letters, written by a fictional figure who commented pointedly about Muscogee Nation, Indian Territory, and United States politics during the period of the dissolution of tribal governments and communal lands. He served as secretary to the Sequoyah Constitutional Convention and drafted much of the constitution for its proposed Native American state, but Congress rejected the proposal. Posey died young, drowned while trying to cross the flooding North Canadian River in Oklahoma.

Chitto Harjo was a leader and orator among the traditionalists in the Muscogee Creek Nation in Indian Territory at the turn of the 20th century. He resisted changes which the US government and local leaders wanted to impose to achieve statehood for what became Oklahoma. These included extinguishing tribal governments and civic institutions and breaking up communal lands into allotments to individual households, with United States sales of the "surplus" to European-American and other settlers. He was the leader of the Crazy Snake Rebellion on March 25, 1909 in Oklahoma. At the time this was called the last "Indian uprising".

The Alabama–Quassarte Tribal Town is both a federally recognized Native American tribe and a traditional township of Muskogean-speaking Alabama and Coushatta peoples. Their traditional languages include Alabama, Koasati, and Mvskoke. As of 2014, the tribe includes 369 enrolled members, who live within the state of Oklahoma as well as Texas, Louisiana, and Arizona.

Redbird Smith (1850–1918) was a traditionalist and political activist in the Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory. He helped found the Nighthawk Keetoowah Society, whose members revitalized traditional spirituality among the Cherokee from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century.

The Crazy Snake Rebellion, also known as the Smoked Meat Rebellion or Crazy Snake's War, was an incident in 1909 that at times was viewed as a war between the Creek people and American settlers. It should not be confused with an earlier, bloodless, conflict in 1901 involving many of the same people. The conflict consisted of only two minor skirmishes, and the first was actually a struggle between a group of marginalized African Americans and a posse formed to punish the alleged robbery of a piece of smoked meat.

An Organic Act is a generic name for a statute used by the United States Congress to describe a territory, in anticipation of being admitted to the Union as a state. Because of Oklahoma's unique history an explanation of the Oklahoma Organic Act needs a historic perspective. In general, the Oklahoma Organic Act may be viewed as one of a series of legislative acts, from the time of Reconstruction, enacted by Congress in preparation for the creation of a united State of Oklahoma. The Organic Act created Oklahoma Territory, and Indian Territory that were Organized incorporated territories of the United States out of the old "unorganized" Indian Territory. The Oklahoma Organic Act was one of several acts whose intent was the assimilation of the tribes in Oklahoma and Indian Territories through the elimination of tribes' communal ownership of property.

Hickory Ground, also known as Otciapofa is an historic Upper Muscogee Creek tribal town and an archaeological site in Elmore County, Alabama near Wetumpka. It is known as Oce Vpofa in the Muscogee language; the name derives from oche-ub,"hickory" and po-fau, "among". It is best known for serving as the last capital of the National Council of the Creek Nation, prior to the tribe being moved to the Indian Territory in the 1830s. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on March 10, 1980.

Sharp v. Murphy, 591 U.S. ___ (2020), was a Supreme Court of the United States case of whether Congress disestablished the Muscogee (Creek) Nation reservation. After holding the case from the 2018 term, the case was decided on July 9, 2020, in a per curiam decision following McGirt v. Oklahoma that, for the purposes of the Major Crimes Act, the reservations were never disestablished and remain Native American country.