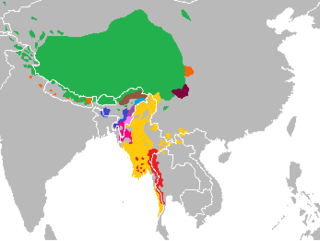

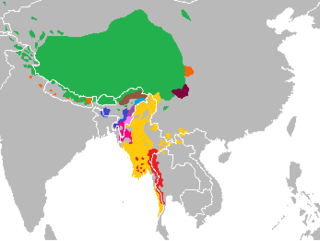

Sino-Tibetan, also cited as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. Around 1.4 billion people speak a Sino-Tibetan language. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Sinitic languages. Other Sino-Tibetan languages with large numbers of speakers include Burmese and the Tibetic languages. Other languages of the family are spoken in the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif, and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Most of these have small speech communities in remote mountain areas, and as such are poorly documented.

Tani, is a branch of Tibeto-Burman languages spoken mostly in Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, and neighboring regions.

Tshangla is a Sino-Tibetan language of the Bodish branch closely related to the Tibetic languages. Tshangla is primarily spoken in Eastern Bhutan and acts as a lingua franca in the region; it is also spoken in the adjoining Tawang tract in the Indian state of Arunachal Pradesh and the Pemako region of Tibet. Tshangla is the principal pre-Tibetan language of Bhutan.

The Himalayan Languages Project, launched in 1993, is a research collective based at Leiden University and comprising much of the world's authoritative research on the lesser-known and endangered languages of the Himalayas, in Nepal, China, Bhutan, and India. Its members regularly spend months or years at a time doing field research with native speakers. The Director of the Himalayan Languages Project is George van Driem. Project members include Mark Turin and Jeroen Wiedenhof. The project recruits graduate students to collect field data on little-known languages for their Ph.D. dissertations.

There are two dozen languages of Bhutan, all members of the Tibeto-Burman language family except for Nepali, which is an Indo-Aryan language, and Bhutanese Sign Language. Dzongkha, the national language, is the only native language of Bhutan with a literary tradition, though Lepcha and Nepali are literary languages in other countries. Other non-Bhutanese minority languages are also spoken along Bhutan's borders and among the primarily Nepali-speaking Lhotshampa community in South and East Bhutan. Chöke is the language of the traditional literature and learning of the Buddhist monastics.

The Khengkha language, or Kheng, is an East Bodish language spoken by ~40,000 native speakers worldwide, in the Zhemgang, Trongsa, and Mongar districts of south–central Bhutan.

The Kiranti languages are a major family of Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in Nepal and India by the Kirati people.

The Sal languages, also known as the Brahmaputran languages, are a branch of Tibeto-Burman languages spoken in northeast India, as well as parts of Bangladesh, Myanmar (Burma), and China.

Raji–Raute is a branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family that includes the three closely related languages, namely Raji, Raute, and Rawat. They are spoken by small hunter-gatherer communities in the Terai region of Nepal and in neighboring Uttarakhand, India.

Bodish, named for the Tibetan ethnonym Bod, is a proposed grouping consisting of the Tibetic languages and associated Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in Tibet, North India, Nepal, Bhutan, and North Pakistan. It has not been demonstrated that all these languages form a clade, characterized by shared innovations, within Sino-Tibetan.

The Tibeto-Kanauri languages, also called Bodic, Bodish–Himalayish, and Western Tibeto-Burman, are a proposed intermediate level of classification of the Sino-Tibetan languages, centered on the Tibetic languages and the Kinnauri dialect cluster. The conception of the relationship, or if it is even a valid group, varies between researchers.

The West Himalayish languages, also known as Almora and Kanauric, are a family of Sino-Tibetan languages centered in Himachal Pradesh, Uttarakhand and across the border into Nepal. LaPolla (2003) proposes that the West Himalayish languages may be part of a larger "Rung" group.

The East Bodish languages are a small group of non-Tibetic Bodish languages spoken in eastern Bhutan and adjacent areas of Tibet and India. They include:

The Kurtöp language is an East Bodish language spoken in Kurtoe Gewog, Lhuntse District, Bhutan. In 1993, there were about 10,000 speakers of Kurtöp.

The Tibeto-Burman languages are the non-Sinitic members of the Sino-Tibetan language family, over 400 of which are spoken throughout the Southeast Asian Massif ("Zomia") as well as parts of East Asia and South Asia. Around 60 million people speak Tibeto-Burman languages. The name derives from the most widely spoken of these languages, Burmese and the Tibetic languages, which also have extensive literary traditions, dating from the 12th and 7th centuries respectively. Most of the other languages are spoken by much smaller communities, and many of them have not been described in detail.

Gongduk or Gongdu is an endangered Sino-Tibetan language spoken by about 1,000 people in a few inaccessible villages located near the Kuri Chhu river in the Gongdue Gewog of Mongar District in eastern Bhutan. The names of the villages are Bala, Dagsa, Damkhar, Pam, Pangthang, and Yangbari (Ethnologue).

The Baram–Thangmi languages, Baram and Thangmi are Tibeto-Burman languages spoken in Nepal. They are classified as part of the Newaric branch by van Driem (2003) and Turin (2004), who view Newar as being most closely related to Baram–Thangmi.

Lhokpu, also Lhobikha or Taba-Damey-Bikha, is one of the autochthonous languages of Bhutan spoken by the Lhop people. It is spoken in southwestern Bhutan along the border of Samtse and Chukha Districts. Van Driem (2003) leaves it unclassified as a separate branch within the Sino-Tibetan language family.

ʼOle, also called ʼOlekha or Black Mountain Monpa, is a possibly Sino-Tibetan language spoken by about 1,000 people in the Black Mountains of Wangdue Phodrang and Trongsa Districts in western Bhutan. The term ʼOle refers to a clan of speakers.

The East Asian languages are a language family proposed by Stanley Starosta in 2001. The proposal has since been adopted by George van Driem and others.