The Helvetic Confessions are two documents expressing the common belief of Calvinist churches, especially in Switzerland.

The Helvetic Confessions are two documents expressing the common belief of Calvinist churches, especially in Switzerland.

The First Helvetic Confession (Latin : Confessio Helvetica prior), known also as the Second Confession of Basel, was drawn up in Basel in 1536 by Heinrich Bullinger and Leo Jud of Zürich, Kaspar Megander of Bern, Oswald Myconius and Simon Grynaeus of Basel, Martin Bucer and Wolfgang Capito of Strasbourg, with other representatives from Schaffhausen, St Gall, Mühlhausen and Biel. The first draft was written in Latin and the Zürich delegates objected to its Lutheran phraseology. However, Leo Jud's German translation was accepted by all, and after Myconius and Grynaeus had modified the Latin form, both versions were agreed to and adopted on February 26, 1536. [1] It was an attempted Reformed-Lutheran symbol of unity and brought by Bucer and Capito to Martin Luther, who ultimately rejected it. [2]

Chapters of the First Helvetic Confession:

| Latin [3] | English [4] |

|---|---|

| I. De Scriptura Sacra. | I. On the Sacred Scripture. |

| II. De Interpretatione Scripturæ. | II. On the Interpretation of Scripture. |

| III. De Antiquis Patribus. | III. Of the Ancient Fathers. |

| IV. De Traditionibus Hominum. | IV. On the Traditions of Men. |

| V. Scopus Scripturæ. | V. The scope of Scripture. |

| VI. Deus. | VI. God. |

| VII. Homo et Vires ejus. | VII. Man and his strengths. |

| VIII. Originale Peccatum. | VIII. Original Sin. |

| IX. Liberum Arbitrium. | IX. Free will. |

| X. Consilium Dei Æternum de Reparatione Hominis. | X. The Eternal Counsel of God on the Restoration of Man. |

| XI. Jesus Christus et quæ per Christum. | XI. Jesus Christ and the things that come through Christ. |

| XII. Scopus Evangelicæ Doctrinæ. | XII. The scope of the Evangelical Doctrine. |

| XIII. Christianus et Officia ejus. | XIII. Christian and his Responsibilities. |

| XIV. De Fide. | XIV. Faith. |

| XV. Ecclesia. | XV. Church. |

| XVI. De Ministerio Verbi. | XVI. On the Ministry of the Word. |

| XVII. Potestas Ecclesiastica. | XVII. Ecclesiastical power. |

| XVIII. Electio Ministrorum. | XVIII. Election of Ministers. |

| XIX. Pastor Quis. | XIX. Who is the shepherd. |

| XX. Ministrorum Officia. | XX. The Responsibility of the Ministers. |

| XXI. De Vi et Efficacia Sacramentorum. | XXI. On the Strength and Effectiveness of the Sacraments. |

| XXII. Baptisma. | XXI. Baptism. |

| XXIII. Eucharistia. | XXIII. The Eucharist. |

| XXIV. Cœtus Sacri. | XXIV. The Sacred Congregation. |

| XXV. De Mediis. | XXV. The Middle. ( means ) |

| XXVI. De Hæreticis et Schismaticis. | XXVI. Of the Heretics and Dissidents. |

| XXVII. De Magistratu. | XXVII. The Magistrate. |

| XXVIII. De Sancto Conjugio. | XXVII. The Holy Marriage. |

The Second Helvetic Confession (Latin: Confessio Helvetica posterior) was written by Bullinger in 1562 and revised in 1564 as a private exercise. It came to the notice of Elector Palatine Frederick III, who had it translated into German and published. [1] It was attractive to some Reformed leaders as a corrective to what they saw as the overly Lutheran statements of the Strasbourg Consensus. An attempt was made in early 1566 to have all the churches of Switzerland sign the Second Helvetic Confession as a common statement of faith. [5] It gained a favorable hold on the Swiss churches, who had found the First Confession too short and too Lutheran. [1] However, "the Basel clergy refused to sign the confession, stating that although they found no fault with it, they preferred to stand by their own Basel Confession of 1534". [5]

Chapters of the Second Helvetic Confession:

| Latin [6] | English [7] |

|---|---|

| I. De Scriptura sancta, vero Dei Verbo. | I. Of The Holy Scripture Being The True Word of God. |

| II.De interpretandis Scripturis sanctis, et de Patribus, Conciliis, et Traditionibus. | II.Of Interpreting The Holy Scripture; and of Fathers, Councils, and Traditions. |

| III. De Deo, Vnitate Ejus ac Trinitate. | III. Of God, His Unity and Trinity. |

| IV. De idolis vel imaginibus Dei, Christi et Divorum. | IV. Of Idols or Images of God, Christ and The Saints. |

| V. De adoratione, cultu et invocatione Dei per unicum mediatorem Jesum Christum. | V. Of The Adoration, Worship and Invocation of God Through The Only Mediator Jesus Christ. |

| VI. De providentia Dei. | VI. Of the Providence of God. |

| VII. De creatione rerum omnium, de Angelis, Diabolo et Homine. | VII. Of The Creation of All Things: Of Angels, the Devil, and Man. |

| VIII. De lapsu hominis et peccato, et causa peccati. | VIII. Of Man's Fall, Sin and the Cause of Sin. |

| IX. De libero arbitrio adeoque viribus hominis. | IX. Of Free Will, and Thus of Human Powers. |

| X. De praedestinatione Dei et Electione Sanctorum. | X. Of the Predestination of God and the Election of the Saints. |

| XI. De Jesu Christo, vero Deo et Homine, unico mundi Salvatore. | XI. Of Jesus Christ, True God and Man, the Only Savior of the World. |

| XII. De Lege Dei. | XII. Of the Law of God. |

| XIII. De Evangelio Jesu Christi, de Promissionibus item, Spiritu et Litera. | XIII. Of the Gospel of Jesus Christ, of the Promises, and of the Spirit and Letter. |

| XIV. De poenitentia et conversione Hominis. | XIV. Of Repentance and the Conversion of Man. |

| XV. De vera fidelium justificatione. | XV. Of the True Justification of the Faithful. |

| XVI. De fide et bonis operibus, eorumque mercede, et merito hominis. | XVI. Of Faith and Good Works, and of Their Reward, and of Man's Merit. |

| XVII. De catholica et sancta Dei Ecclesia et unico capite Ecclesiae. | XVII. Of The Catholic and Holy Church of God, and of The One Only Head of The Church. |

| XVIII. De ministris Ecclesiae ipsorumque institutione et officiis. | XVIII. Of The Ministers of The Church, Their Institution and Duties. |

| XIX. De sacramentis Ecclesiae Christi. | XIX. Of the Sacraments of the Church of Christ. |

| XX. De sancto Baptismo. | XX. Of Holy Baptism. |

| XXI. De sacra Coena Domini. | XXI. Of the Holy Supper of the Lord. |

| XXII. De coetibus sacris et Ecclesiasticis. | XXII. Of Religious and Ecclesiastical Meetings. |

| XXIII. De precibus ecclesiae, cantu et horis canonicis. | XXIII. Of the Prayers of the Church, of Singing, and of Canonical Hours. |

| XXIV. De feriis, jejuniis, ciborumque delectu. | XXIV. Of Holy Days, Fasts and the Choice of Foods. |

| XXV. De Catechesi et aegrotantium consolatione vel visitatione. | XXV. Of Catechizing and of Comforting and Visiting the Sick. |

| XXVI. De sepultura fidelium curaque pro mortuis gerenda, de purgatorio et apparitione spirituum. | XXVI. Of the Burial of the Faithful, and of the Care to Be Shown for the Dead; of Purgatory, and the Appearing of Spirits. |

| XXVII. De ritibus et caeremoniis et mediis. | XXVII. Of Rites, Ceremonies and Things Indifferent. |

| XXVIII. De bonis ecclesiae. | XXVIII. Of the possessions of the Church. |

| XXIX. De coelibatu, conjugio et oeconomia. | XXIX. Of Celibacy, Marriage and the Management of Domestic Affairs. |

| XXX. De Magistratu. | XXX. Of the Magistracy. |

| Part of a series on |

| Calvinism |

|---|

|

| |

The Second Helvetic Confession was adopted by the Reformed Church not only throughout Switzerland but in Scotland (1566), Hungary (1567), France (1571), and Poland (1578). Along with the Thirty-nine Articles, the Westminster Confession of Faith, the Scots Confession and the Heidelberg Catechism is one the most generally recognized confessions of the Reformed Church. [1] The Second Helvetic Confession was also included in the United Presbyterian Church in the U.S.A.'s Book of Confessions, in 1967, and remains in the Book of Confessions adopted by the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.). [8]

Mary is mentioned several times in the Second Helvetic Confession, which expounds Bullinger's mariology. Chapter Three quotes the angel's message to the Virgin Mary, " – the Holy Spirit will come over you " – as an indication of the existence of the Holy Spirit and the Trinity. The Latin text described Mary as diva, indicating her rank as a person, who dedicated herself to God. In Chapter Nine, the Virgin birth of Jesus is said to be conceived by the Holy Spirit and born without the participation of any man. The Second Helvetic Confession accepted the "Ever Virgin" notion from John Calvin, which spread throughout much of Europe with the approbation of this document in the above-mentioned countries. [9] Bullinger's 1539 polemical treatise against idolatry [10] expressed his belief that Mary's "sacrosanctum corpus" ("sacrosanct body") had been assumed into heaven by angels:

Hac causa credimus et Deiparae virginis Mariae purissimum thalamum et spiritus sancti templum, hoc est, sacrosanctum corpus ejus deportatum esse ab angelis in coelum. [11] For this reason we believe that the Virgin Mary, Begetter of God, the most pure bed and temple of the Holy Spirit, that is, her most holy body, was carried to heaven by angels. [12]

The Athanasian Creed — also called the Pseudo-Athanasian Creed or Quicunque Vult, which is both its Latin name and its opening words, meaning "Whosoever wishes" — is a Christian statement of belief focused on Trinitarian doctrine and Christology. Used by Christian churches since the early sixth century, it was the first creed to explicitly state the equality of the three hypostases of the Trinity. It differs from the Nicene-Constantinopolitan Creed and the Apostles' Creed in that it includes anathemas condemning those who disagree with its statements.

The Apostles' Creed, sometimes titled the Apostolic Creed or the Symbol of the Apostles, is a Christian creed or "symbol of faith".

Continental Reformed Protestantism is a part of the Calvinist tradition within Protestantism that traces its origin in the European continent. Prominent subgroups are the Dutch Reformed, the Swiss Reformed, the French Reformed (Huguenots), the Hungarian Reformed, and the Waldensian Church in Italy.

Heinrich Bullinger was a Swiss Reformer and theologian, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster. One of the most important leaders of the Swiss Reformation, Bullinger co-authored the Helvetic Confessions and collaborated with John Calvin to work out a Reformed doctrine of the Lord's Supper.

This article contains information about the literary events and publications of 1536.

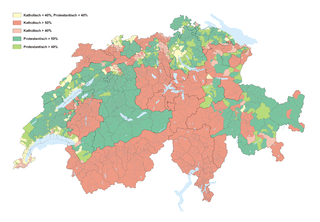

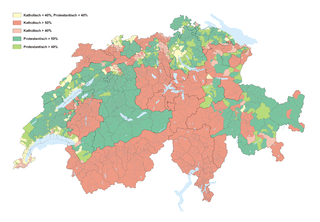

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland was promoted initially by Huldrych Zwingli, who gained the support of the magistrate, Mark Reust, and the population of Zürich in the 1520s. It led to significant changes in civil life and state matters in Zürich and spread to several other cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy. Seven cantons remained Catholic, however, which led to intercantonal wars known as the Wars of Kappel. After the victory of the Catholic cantons in 1531, they proceeded to institute Counter-Reformation policies in some regions. The schism and distrust between the Catholic and the Protestant cantons defined their interior politics and paralysed any common foreign policy until well into the 18th century.

Leo Jud, known to his contemporaries as Meister Leu, was a Swiss reformer who worked with Huldrych Zwingli in Zürich.

God the Son is the second person of the Trinity in Christian theology. The doctrine of the Trinity identifies the Logos (Jesus) as the incarnation of God. United in essence (consubstantial), but distinct in person with regard to God the Father and God the Holy Spirit.

Samuel Werenfels was a Swiss theologian. He was a major figure in the move towards a "reasonable orthodoxy" in Swiss Reformed theology.

The reformed confessions of faith are the confessional documents of various Calvinist churches. These express the doctrinal views of the churches adopting the confession. Confessions play a crucial part in the theological identity of reformed churches, either as standards to which ministers must subscribe, or more generally as accurate descriptions of their faith. Most confessions date to the 16th and 17th century.

The Helvetic Consensus is a Swiss Reformed profession of faith drawn up in 1675 to guard against doctrines taught at the French Academy of Saumur, especially Amyraldism.

The Reformed branch of Protestantism in Switzerland was started in Zürich by Huldrych Zwingli and spread within a few years to Basel, Bern, St. Gallen,(Joachim Vadian), to cities in southern Germany and via Alsace to France.

The Protestant Church in Switzerland (PCS), formerly named Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches until 31 December 2019, is a federation of 25 member churches – 24 cantonal churches and the Evangelical-Methodist Church of Switzerland. The PCS is not a church in a theological understanding, because every member is independent with their own theological and formal organisation. It serves as a legal umbrella before the federal government and represents the church in international relations. Except for the Evangelical-Methodist Church, which covers all of Switzerland, the member churches are restricted to a certain territory.

The theology of Ulrich Zwingli was based on an interpretation of the Bible, taking scripture as the inspired word of God and placing its authority higher than what he saw as human sources such as the ecumenical councils and the church fathers. He also recognised the human element within the inspiration, noting the differences in the canonical gospels. Zwinglianism is the Reformed confession based on the Second Helvetic Confession promulgated by Zwingli's successor Heinrich Bullinger in the 1560s.

The Altered Augsburg Confession is a later version of the Lutheran Augsburg Confession that includes substantial differences with regard to holy communion and the presence of Christ in bread and wine.

The Consensus Tigurinus or Consensus of Zurich was a Protestant document written in 1549 by John Calvin and Heinrich Bullinger.

The Augsburg Confession, also known as the Augustan Confession or the Augustana from its Latin name, Confessio Augustana, is the primary confession of faith of the Lutheran Church and one of the most important documents of the Protestant Reformation. The Augsburg Confession was written in both German and Latin and was presented by a number of German rulers and free-cities at the Diet of Augsburg on 25 June 1530.

Published in 1581, the Harmonia confessionum fidei was an early attempt at Protestant comparative dogmatics or symbolics.

Simon Sulzer was a Reformed theologian, Reformer, and Antistes of the Basel church.

{{cite web}}: External link in |website=