The Helvetic Consensus (Latin : Formula consensus ecclesiarum Helveticarum) is a Swiss Reformed profession of faith drawn up in 1675 to guard against doctrines taught at the French Academy of Saumur, especially Amyraldism.

The Helvetic Consensus (Latin : Formula consensus ecclesiarum Helveticarum) is a Swiss Reformed profession of faith drawn up in 1675 to guard against doctrines taught at the French Academy of Saumur, especially Amyraldism.

The definition of the doctrines of election and reprobation by the Synod of Dort (1618–1619) occasioned a reaction in France, where the Protestants lived surrounded by Roman Catholics. Moise Amyraut, professor at Saumur, taught that the atonement of Jesus was hypothetically universal rather than particular and definite. His colleague, Louis Cappel, denied the verbal inspiration of the Hebrew text of the Old Testament, and Josué de la Place rejected the immediate imputation of Adam's sin as arbitrary and unjust.

The famous and flourishing school of Saumur came to be looked upon with increasing mistrust as the seat of heterodoxy, especially by the Swiss, who were in the habit of sending students there. The first impulse to attack the new doctrine came from Geneva, seat of historical Calvinism. In 1635 Friedrich Spanheim wrote against Amyraut, whom the clergy of Paris tried to defend. In course of time Amyraldism gained ground in Geneva. In 1649, Alexander Morus, the successor of Spanheim, but suspected of belonging to the liberal party, was compelled by the magistrates of Geneva to subscribe to a series of articles in the form of theses and antitheses, the first germ of the Formula consensus. His place was taken by Philippe Mestrezat, and later by Louis Tronchin (de), both inclined toward the liberal tendency of France, while Francis Turretin defended the traditional system. Mestrezat induced the Council of Geneva to take a moderate stand point in the article on election, but the other cantons of Switzerland objected to this new tendency and threatened to stop sending their pupils to Geneva.

The Council of Geneva submitted and peremptorily demanded from all candidates subscription to the older articles. But the conservative elements were not satisfied, and the idea occurred to them to stop the further spread of such novelties by establishing a formula obligatory upon all teachers and preachers. After considerable discussion between Lucas Gernler of Basel, Hummel of Bern, Ott of Schaffhausen, Johann Heinrich Heidegger of Zürich, and others, the last mentioned was charged with drawing up the formula. In the beginning of 1675, Heidegger's Latin draft was communicated to the ministers of Zurich; and in the course of the year it received very general adoption, and almost everywhere was added as an appendix and exposition to the Helvetic Confession.

The Consensus consists of a preface and twenty-five canons, and states clearly the difference between strict Calvinism and the school of Saumur.

Although the Helvetic Consensus was introduced everywhere in the Reformed Church of Switzerland, it did not long hold its position. At first, circumspection and tolerance were shown at the enforcement of its signature, but as soon as many French preachers sought positions in Vaud after the revocation of the edict of Nantes, it was ordered that all who intended to preach must sign the Consensus without reservation. An address of the Great Elector of Brandenburg to the Reformed cantons, in which, in consideration of the dangerous position of Protestantism and the need of a union of all Evangelicals, he asked for a nullification of the separating formula, brought it about that the signature was not demanded in Basel after 1686, and it was also dropped in Schaffhausen and later (1706) in Geneva, while Zurich and Bern retained it.

Meanwhile, the whole tendency of the time had changed. Secular science stepped into the foreground. The practical, ethical side of Christianity began to gain a dominating influence. Rationalism and Pietism undermined the foundations of the old orthodoxy. An agreement between the liberal and conservative parties was temporarily attained insofar that it was decided that the Consensus was not to be regarded as a rule of faith, but only as a norm of teaching. In 1722 Prussia and England applied to the respective magistracies of the Swiss cantons for the abolition of the formula for the sake of the unity and peace of the Protestant Churches. The reply was somewhat evasive, but, though the formula was never formally abolished, it gradually fell entirely into disuse.

Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation, a schism in the Roman Catholic Church. Today, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed, Presbyterian, Reformed Anglican, Congregationalist, and Reformed Baptist denominational families.

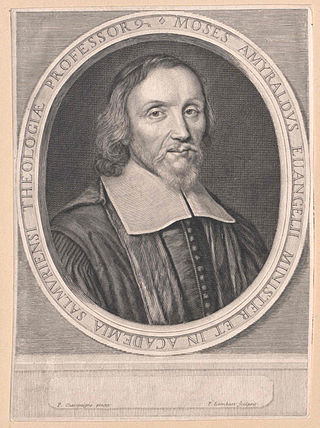

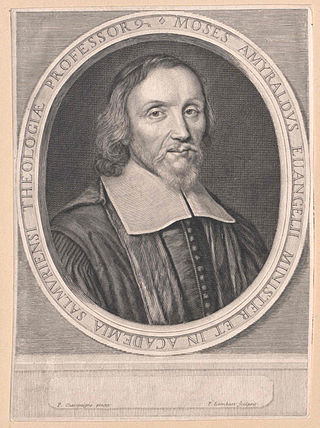

Moïse Amyraut, Latin Moyses Amyraldus, in English texts often Moses Amyraut, was a French Huguenot, Reformed theologian and metaphysician. He was the architect of Amyraldism, a Calvinist doctrine that made modifications to Calvinist theology regarding the nature of Christ's atonement and covenant theology.

Heinrich Bullinger was a Swiss Reformer and theologian, the successor of Huldrych Zwingli as head of the Church of Zürich and a pastor at the Grossmünster. One of the most important leaders of the Swiss Reformation, Bullinger co-authored the Helvetic Confessions and collaborated with John Calvin to work out a Reformed doctrine of the Lord's Supper.

The Helvetic Republic was a sister republic of France that existed between 1798 and 1803, during the French Revolutionary Wars. It was created following the French invasion and the consequent dissolution of the Old Swiss Confederacy, marking the end of the ancien régime in Switzerland. Throughout its existence, the republic incorporated most of the territory of modern Switzerland, excluding the cantons of Geneva and Neuchâtel and the old Prince-Bishopric of Basel.

William Farel, Guilhem Farel or Guillaume Farel, was a French evangelist, Protestant reformer and a founder of the Calvinist Church in the Principality of Neuchâtel, in the Republic of Geneva, and in Switzerland in the Canton of Bern and the Canton of Vaud. He is most often remembered for having persuaded John Calvin to remain in Geneva in 1536, and for persuading him to return there in 1541, after their expulsion in 1538. They influenced the government of Geneva to the point that it became the "Protestant Rome", where Protestants took refuge and dissidents such as Catholics and unitarians were driven out, some were even killed for their beliefs. Together with Calvin, Farel worked to train missionary preachers who spread the Protestant cause to other countries, and especially to France.

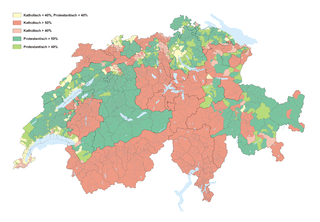

The Protestant Reformation in Switzerland was promoted initially by Huldrych Zwingli, who gained the support of the magistrate, Mark Reust, and the population of Zürich in the 1520s. It led to significant changes in civil life and state matters in Zürich and spread to several other cantons of the Old Swiss Confederacy. Seven cantons remained Catholic, however, which led to intercantonal wars known as the Wars of Kappel. After the victory of the Catholic cantons in 1531, they proceeded to institute Counter-Reformation policies in some regions. The schism and distrust between the Catholic and the Protestant cantons defined their interior politics and paralysed any common foreign policy until well into the 18th century.

Francis Turretin was a Genevan-Italian Reformed scholastic theologian.

The Helvetic Confessions are two documents expressing the common belief of Calvinist churches, especially in Switzerland.

Johann Heinrich Heidegger, Swiss theologian, was born at Bäretswil, in the Canton of Zürich.

Amyraldism is a Calvinist doctrine. It is also known as the School of Saumur, post redemptionism, moderate Calvinism, or hypothetical universalism. It is one of several hypothetical universalist systems.

The reformed confessions of faith are the confessional documents of various Reformed churches. These express the doctrinal views of the churches adopting the confession. Confessions play a crucial part in the theological identity of reformed churches, either as standards to which ministers must subscribe, or more generally as accurate descriptions of their faith. Most confessions date to the 16th and 17th century.

Josué de la Place was a Reformed theologian who was born at Saumur, France. He is known as the originator of the "mediate view" of the imputation of sin, whereby original sin is considered to be an inherent depravity in man. This view is opposed to the "federalist view", whereby the God immediately imputes original sin to all men, as a consequence of Adam's sin, and thus this original sin becomes the cause of actual sin.

The Protestant Church in Switzerland (PCS), formerly named Federation of Swiss Protestant Churches until 31 December 2019, is a federation of 25 member churches – 24 cantonal churches and the Evangelical-Methodist Church of Switzerland. The PCS is not a church in a theological understanding, because every member is independent with their own theological and formal organisation. It serves as a legal umbrella before the federal government and represents the church in international relations. Except for the Evangelical-Methodist Church, which covers all of Switzerland, the member churches are restricted to a certain territory.

The theology of Ulrich Zwingli was based on an interpretation of the Bible, taking scripture as the inspired word of God and placing its authority higher than what he saw as human sources such as the ecumenical councils and the church fathers. He also recognised the human element within the inspiration, noting the differences in the canonical gospels. Zwinglianism is the Reformed confession based on the Second Helvetic Confession promulgated by Zwingli's successor Heinrich Bullinger in the 1560s.

The Academy of Saumur was a Huguenot university at Saumur in western France. It existed from 1593, when it was founded by Philippe de Mornay, until shortly after 1685, when Louis XIV decided on the revocation of the Edict of Nantes, ending the limited toleration of Protestantism in France.

Hypothetical universalism is the belief that Christ died in some sense for every person, but his death effected salvation only for those who were predestined for salvation. In the history of Reformed theology, there have been several examples of hypothetical universalist systems, all of which are considered errant by traditional Calvinism. Amyraldism is one of these, but hypothetical universalism as a whole is sometimes erroneously equated with it. Hypothetical universalism is believed to be outside the bounds of the Reformed tradition. For example, Canon VI states

Wherefore, we can not agree with the opinion of those who teach: l) that God, moved by philanthropy, or a kind of special love for the fallen of the human race, did, in a kind of conditioned willing, first moving of pity, as they call it, or inefficacious desire, determine the salvation of all, conditionally, i.e., if they would believe, 2) that he appointed Christ Mediator for all and each of the fallen; and 3) that, at length, certain ones whom he regarded, not simply as sinners in the first Adam, but as redeemed in the second Adam, he elected, that is, he determined graciously to bestow on these, in time, the saving gift of faith; and in this sole act election properly so-called is complete. For these and all other similar teachings are in no way insignificant deviations from the proper teaching concerning divine election; because the Scriptures do not extend unto all and each God’s purpose of showing mercy to man, but restrict it to the elect alone, the reprobate being excluded even by name, as Esau, whom God hated with an eternal hatred. The same Holy Scriptures testify that the counsel and will of God do not change, but stand immovable, and God in the heavens does whatsoever he will ; for God is infinitely removed from all that human imperfection which characterizes inefficacious affections and desires, rashness repentance and change of purpose. The appointment, also, of Christ, as Mediator, equally with the salvation of those who were given to him for a possession and an inheritance that can not be taken away, proceeds from one and the same election, and does not form the basis of election.

The Consensus Tigurinus or Consensus of Zurich was a Protestant document written in 1549 by John Calvin and Heinrich Bullinger.

The history of Geneva dates from before the Roman occupation in the second century BC. Now the principal French-speaking city of Switzerland, Geneva was an independent city state from the Middle Ages until the end of the 18th century. John Calvin was the Protestant leader of the city in the 16th century.

Philippe Mestrezat was a Genevan Calvinist minister and professor at Geneva.

Reformed orthodoxy or Calvinist orthodoxy was an era in the history of Calvinism in the 16th to 18th centuries. Calvinist orthodoxy was paralleled by similar eras in Lutheranism and tridentine Roman Catholicism after the Counter-Reformation. Calvinist scholasticism or Reformed scholasticism was a theological method that gradually developed during the era of Calvinist Orthodoxy.

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). "Helvetic Consensus". New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain : Jackson, Samuel Macauley, ed. (1914). "Helvetic Consensus". New Schaff–Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge (third ed.). London and New York: Funk and Wagnalls.