Related Research Articles

In linguistics, a noun class is a particular category of nouns. A noun may belong to a given class because of the characteristic features of its referent, such as gender, animacy, shape, but such designations are often clearly conventional. Some authors use the term "grammatical gender" as a synonym of "noun class", but others consider these different concepts. Noun classes should not be confused with noun classifiers.

French grammar is the set of rules by which the French language creates statements, questions and commands. In many respects, it is quite similar to that of the other Romance languages.

Animacy is a grammatical and semantic feature, existing in some languages, expressing how sentient or alive the referent of a noun is. Widely expressed, animacy is one of the most elementary principles in languages around the globe and is a distinction acquired as early as six months of age.

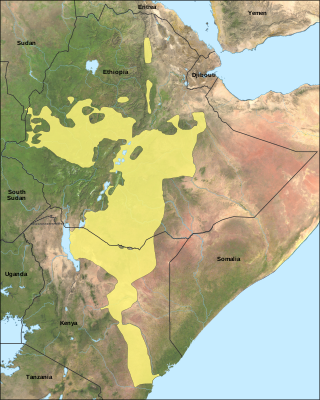

Oromo, historically also called Galla, is an Afroasiatic language that belongs to the Cushitic branch. It is native to the Ethiopian state of Oromia and Northern Kenya and is spoken predominantly by the Oromo people and neighboring ethnic groups in the Horn of Africa. It is used as a lingua franca particularly in the Oromia Region and northeastern Kenya.

Saraiki is an Indo-Aryan language of the Lahnda group, spoken by 26 million people primarily in the south-western half of the province of Punjab in Pakistan. It was previously known as Multani, after its main dialect.

The Ghomara language is a Northern Berber language spoken in Morocco. It is the mother tongue of the Ghomara Berbers, who total around 10,000 people. Ghomara Berber is spoken on the western edge of the Rif, among the Beni Bu Zra and Beni Mansur tribes of the Ghomara confederacy. Despite being listed as endangered, it is still being passed on to children in these areas.

A reflexive pronoun is a pronoun that refers to another noun or pronoun within the same sentence.

Derajat, the plural of the word 'dera', is a cultural region of central Pakistan, located in the region where the provinces of Punjab, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, and Balochistan meet. Derajat is bound by the Indus River to the east, and the Sulaiman Mountains to the west.

Memoni is an Indo-Aryan language spoken by Kathiawari Memons, from the Kathiawar region of Gujarat, India. Memon from Okha Port, Kutch and some other communities from Kathiawad also use Memoni at their homes.

Persian grammar is the grammar of the Persian language, whose dialectal variants are spoken in Iran, Afghanistan, Caucasus, Uzbekistan and Tajikistan. It is similar to that of many other Indo-European languages. The language became a more analytic language around the time of Middle Persian, with fewer cases and discarding grammatical gender. The innovations remain in Modern Persian, which is one of the few Indo-European languages to lack grammatical gender, even in pronouns.

In linguistics, agreement or concord occurs when a word changes form depending on the other words to which it relates. It is an instance of inflection, and usually involves making the value of some grammatical category "agree" between varied words or parts of the sentence.

Yiddish grammar is the system of principles which govern the structure of the Yiddish language. This article describes the standard form laid out by YIVO while noting differences in significant dialects such as that of many contemporary Hasidim. As a Germanic language descended from Middle High German, Yiddish grammar is fairly similar to that of German, though it also has numerous linguistic innovations as well as grammatical features influenced by or borrowed from Hebrew, Aramaic, and various Slavic languages.

Garifuna (Karif) is a minority language widely spoken in villages of Garifuna people in the western part of the northern coast of Central America.

Kokborok grammar is the grammar of the Kokborok language, also known as Tripuri or Tipra which is spoken by the Tripuri people, the native inhabitants of the state of Tripura. It is the official language of Tripura, a state located in Northeast India.

Eastern Lombard grammar reflects the main features of Romance languages: the word order of Eastern Lombard is usually SVO, nouns are inflected in number, adjectives agree in number and gender with the nouns, verbs are conjugated in tenses, aspects and moods and agree with the subject in number and person. The case system is present only for the weak form of the pronoun.

Breton is a Brittonic Celtic language in the Indo-European family, and its grammar has many traits in common with these languages. Like most Indo-European languages it has grammatical gender, grammatical number, articles and inflections and, like the other Celtic languages, Breton has mutations. In addition to the singular–plural system, it also has a singulative–collective system, similar to Welsh. Unlike the other Brittonic languages, Breton has both a definite and indefinite article, whereas Welsh and Cornish lack an indefinite article and unlike the other extant Celtic languages, Breton has been influenced by French.

Punjabi is an Indo-Aryan language native to the region of Punjab of Pakistan and India and spoken by the Punjabi people. This page discusses the grammar of Modern Standard Punjabi as defined by the relevant sources below.

East Cree, also known as James Bay (Eastern) Cree, and East Main Cree, is a group of Cree dialects spoken in Quebec, Canada on the east coast of lower Hudson Bay and James Bay, and inland southeastward from James Bay. Cree is one of the most spoken non-official aboriginal languages of Canada. Four dialects have been tentatively identified including the Southern Inland dialect (Iyiniw-Ayamiwin) spoken in Mistissini, Oujé-Bougoumou, Waswanipi, and Nemaska; the Southern Coastal dialect (Iyiyiw-Ayamiwin) spoken in Nemaska, Waskaganish, and Eastmain; the Northern Coastal Dialects (Iyiyiw-Ayimiwin), one spoken in Wemindji and Chisasibi and the other spoken in Whapmagoostui. The dialects are mutually intelligible, though difficulty arises as the distance between communities increases.

Tangale (Tangle) is a West Chadic language spoken in Northern region of Nigeria. The vast majority of the native speakers are found across Akko, Billiri, Kaltungo and Shongom Local Government Area of Gombe State Nigeria.

The morphology of the Welsh language shows many characteristics perhaps unfamiliar to speakers of English or continental European languages like French or German, but has much in common with the other modern Insular Celtic languages: Irish, Scottish Gaelic, Manx, Cornish, and Breton. Welsh is a moderately inflected language. Verbs conjugate for person, tense and mood with affirmative, interrogative and negative conjugations of some verbs. A majority of prepositions inflect for person and number. There are few case inflections in Literary Welsh, being confined to certain pronouns.

References

- ↑ Hindustani (2005). Keith Brown (ed.). Encyclopedia of Language and Linguistics (2 ed.). Elsevier. ISBN 0-08-044299-4.

- 1 2 "Stanford Linguistics Colloquium". stanford.edu. Retrieved 16 February 2016.

- ↑ Sheeraz, Muhammad, and Ayaz Afsar. "Farsi: An Invisible But Loaded Weapon for the Emerging Hijraism in Pakistan." Kashmir Journal of Language Research 14, no. 2 (2011).

- ↑ "Queer language". City: World. The Hindu. TNN. 30 November 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- 1 2 Rehman, Zehra (15 April 2016). "The secret language of South Asia's transgender community". Quartz India. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- ↑ "Hijra Farsi: Secret language knits community - Times of India". The Times of India. 7 October 2013. Retrieved 2019-01-26.

- 1 2 3 4 Awan, Muhammad Safeer; Sheeraz, Muhammad (2011). "Queer but Language: A Sociolinguistic Study of Farsi". International Journal of Humanities and Social Science. 1 (10): 127-135.[ predatory publisher ]

- ↑ Ila, Nagar (2008). Language, gender and identity: the case of kotis in Lucknow-India (Thesis). The Ohio State University.

- ↑ Kundalia, Nidhi. "Queer language". The Hindu. Retrieved June 4, 2022.