Related Research Articles

Louchébem or loucherbem is Parisian and Lyonnaise butchers' slang, similar to Pig Latin and Verlan. It originated in the mid-19th century and was in common use until the 1950s.

Pig Latin is a language game, argot, or cant in which words in English are altered, usually by adding a fabricated suffix or by moving the onset or initial consonant or consonant cluster of a word to the end of the word and adding a vocalic syllable to create such a suffix. For example, Wikipedia would become Ikipediaway. The objective is often to conceal the words from others not familiar with the rules. The reference to Latin is a deliberate misnomer; Pig Latin is simply a form of argot or jargon unrelated to Latin, and the name is used for its English connotations as a strange and foreign-sounding language. It is most often used by young children as a fun way to confuse people unfamiliar with Pig Latin.

A slang is a vocabulary of an informal register, common in verbal conversation but avoided in formal writing. It also sometimes refers to the language generally exclusive to the members of particular in-groups in order to establish group identity, exclude outsiders, or both. The word itself came about in the 18th century and has been defined in multiple ways since its conception.

Nadsat is a fictional register or argot used by the teenage gang members in Anthony Burgess's dystopian novel A Clockwork Orange. Burgess was a linguist and he used this background to depict his characters as speaking a form of Russian-influenced English. The name comes from the Russian suffix equivalent of -teen as in thirteen. Nadsat was also used in Stanley Kubrick's film adaptation of the book.

Jargon or technical language is the specialized terminology associated with a particular field or area of activity. Jargon is normally employed in a particular communicative context and may not be well understood outside that context. The context is usually a particular occupation, but any ingroup can have jargon. The key characteristic that distinguishes jargon from the rest of a language is its specialized vocabulary, which includes terms and definitions of words that are unique to the context, and terms used in a narrower and more exact sense than when used in colloquial language. This can lead outgroups to misunderstand communication attempts. Jargon is sometimes understood as a form of technical slang and then distinguished from the official terminology used in a particular field of activity.

Polari is a form of slang or cant used in Britain by some actors, circus and fairground showmen, professional wrestlers, merchant navy sailors, criminals, sex workers, and, particularly, the gay subculture. There is some debate about its origins, but it can be traced to at least the 19th century and possibly as early as the 16th century. There is a long-standing connection with Punch and Judy street puppet performers, who traditionally used Polari to converse.

In linguistics, a neologism is any relatively recent and isolated term, word, or phrase that nevertheless has achieved popular or institutional recognition, and is becoming accepted into mainstream language. Most definitively, a word can be considered a neologism once it is published in a dictionary.

Shelta is a language spoken by Mincéirí, particularly in Ireland and the United Kingdom. It is widely known as the Cant, to its native speakers in Ireland as de Gammon or Tarri, and to the linguistic community as Shelta; other terms for it include the Seldru, and Shelta Thari, among others. The exact number of native speakers is hard to determine due to sociolinguistic issues but Ethnologue puts the number of speakers at 30,000 in the UK, 6,000 in Ireland, and 50,000 in the US. The figure for at least the UK is dated to 1990; it is not clear if the other figures are from the same source.

Lunfardo is an argot originated and developed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries in the lower classes in Buenos Aires and from there spread to other urban areas nearby, such as the Greater Buenos Aires, Rosario and Montevideo.

Pikey is a slang term, which is pejorative and considered by many to be a slur. It is used mainly in the United Kingdom and in Ireland to refer to people who are of the Traveller community, a set of ethno-cultural groups found primarily in Great Britain and Ireland. It is also used against Romanichal Travellers, Welsh Kale, Scottish Lowland Travellers, Scottish Highland Travellers, and Funfair Travellers.

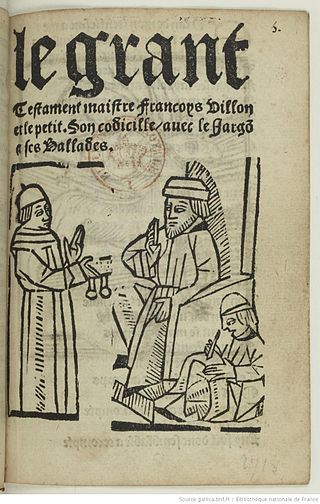

Germanía is the Spanish term for the argot used by criminals or in jails in Spain during 16th and 17th centuries. Its purpose is to keep outsiders out of the conversation. The ultimate origin of the word is the Latin word germanus, through Catalan germà (brother) and germania.

Bargoens is a form of Dutch slang. More specifically, it is a cant language that arose in the 17th century, and was used by criminals, tramps and travelling salesmen as a secret code, like Spain's Germanía or French Argot. It is speculated to originate from Rotwelsch.

Quinqui jargon is associated with quincalleros, semi-nomadic people who live mainly in the northern half of Spain. They prefer to be called mercheros. They are reduced in number and possibly vanishing as a distinct group.

In sociolinguistics, a register is a variety of language used for a particular purpose or particular communicative situation. For example, when speaking officially or in a public setting, an English speaker may be more likely to follow prescriptive norms for formal usage than in a casual setting, for example, by pronouncing words ending in -ing with a velar nasal instead of an alveolar nasal, choosing words that are considered more "formal", and refraining from using words considered nonstandard, such as ain't and y'all.

Thieves' cant is a cant, cryptolect, or argot which was formerly used by thieves, beggars, and hustlers of various kinds in Great Britain and to a lesser extent in other English-speaking countries. It is now mostly obsolete and used in literature and fantasy role-playing, although individual terms continue to be used in the criminal subcultures of Britain and the United States.

Prison slang is an argot used primarily by criminals and detainees in correctional institutions. It is a form of anti-language. Many of the terms deal with criminal behavior, incarcerated life, legal cases, street life, and different types of inmates. Prison slang varies depending on institution, region, and country. Prison slang can be found in other written forms such as diaries, letters, tattoos, ballads, songs, and poems. Prison slang has existed as long as there have been crime and prisons; in Charles Dickens' time it was known as "thieves' cant". Words from prison slang often eventually migrate into common usage, such as "snitch", "ducking", and "narc". Terms can also lose meaning or become obsolete such as "slammer" and "bull-derm."

Back slang is an English coded language in which the written word is spoken phonemically backwards.

An anti-society is a small, separate community intentionally created within a larger society as an alternative to or resistance of it. For example, Adam Podgórecki studied one anti-society composed of Polish prisoners; Bhaktiprasad Mallik of Sanskrit College studied another composed of criminals in Calcutta.

References

- 1 2 3 4 McArthur, T. (ed.) The Oxford Companion to the English Language (1992) Oxford University Press ISBN 0-19-214183-X

- ↑ Rorty, Richard (2001). Redemption from Egotism: James and Proust as Spiritual Exercises. The Estate of Richard Rorty. p. 390. ISBN 978-1-4051-9831-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Kirk, J. & Ó Baoill, D. Travellers and their Language (2002) Queen's University Belfast ISBN 0-85389-832-4

- 1 2 Collins English Dictionary 21st Century Edition (2001) HarperCollins ISBN 0-00-472529-8

- ↑ Schwartz, Robert M. "Interesting Facts about Convicts of France in the 19th Century". Mt. Holyoke University. Archived from the original on 2021-07-03. Retrieved 2019-04-26.

- ↑ Guiraud, Pierre, L'Argot. Que sais-je?, Paris: PUF, 1958, p. 700

- ↑ Carol De Dobay Rifelj (1987). Word and Figure: The Language of Nineteenth-Century French Poetry. Ohio State University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780814204221.

- 1 2 Valdman, Albert (May 2000). "La Langue des faubourgs et des banlieues: de l'argot au français populaire". The French Review (in French). American Association of Teachers of French. 73 (6): 1179–1192. JSTOR 399371.

- 1 2 Hukill, Peter B.; H., A. L.; Jackson, James L. (1961). "The Spoken Language of Medicine: Argot, Slang, Cant". American Speech. 36 (2): 145–151. doi:10.2307/453853. JSTOR 453853.

- 1 2 3 4 Halliday, M. a. K. (1976-09-01). "Anti-Languages". American Anthropologist. 78 (3): 570–584. doi:10.1525/aa.1976.78.3.02a00050. ISSN 1548-1433.

- 1 2 Baker, Paul (2002). Polari The Lost Language of Gay Men. Routledge. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-0415261807.

- ↑ Zarzycki, Łukasz. "Socio-lingual Phenomenon of the Anti-language of Polish and American Prison Inmates" (PDF). Crossroads.

- 1 2 Kohn, Liberty. "Antilanguage and a Gentleman's Goloss: Style, Register, and Entitlement To Irony in A Clockwork Orange" (PDF). ESharp: 1–27.

- ↑ Martin Montgomery (January 1986), "Language and subcultures: Anti-language", An introduction to language and society, Methuen, ISBN 9780416346305

- ↑ "Polari: The Lost Language of Gay Men", Lancaster University. Department of Linguistics and English Language.

- ↑ Bradley M, "The secret ones", New Scientist, 31 May 2014, pp. 42-45

- ↑ Fowler, Roger (Summer 1979). "Anti-Language in Fiction". Style. 13 (3): 259–278. JSTOR 42945250.

- ↑ Dolan 2006, pp. 43.

- ↑ O'Crohan 1987.

- ↑ Partridge, Eric (1937) Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English

- ↑ Pstrusińska, Jadwiga (2013). Secret languages of Afghanistan and their speakers. Cambridge Scholars Publ. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4438-4970-8. OCLC 864565715.

- ↑ Ribton-Turner, C. J. 1887 Vagrants and Vagrancy and Beggars and Begging, London, 1887, p.245, quoting an examination taken at Salford Gaol

- ↑ Mallik, Bhaktiprasad (1972). Language of the underworld of West Bengal. Sanskrit College.