Nataraja, also known as Adalvallan, is a depiction of Shiva, one of the main deities in Hinduism, as the divine cosmic dancer. His dance is called the tandava. The pose and artwork are described in many Hindu texts such as the Tevaram and Thiruvasagam in Tamil and the Amshumadagama and Uttarakamika agama in Sanskrit and the Grantha texts. The dance murti featured in all major Hindu temples of Shaivism, and is a well-known sculptural symbol in India and popularly used as a symbol of Indian culture, as one of the finest illustrations of Hindu art. This form is also referred to as Kuththan, Sabesan, and Ambalavanan in various Tamil texts.

The serpent, or snake, is one of the oldest and most widespread mythological symbols. The word is derived from Latin serpens, a crawling animal or snake. Snakes have been associated with some of the oldest rituals known to humankind and represent dual expression of good and evil.

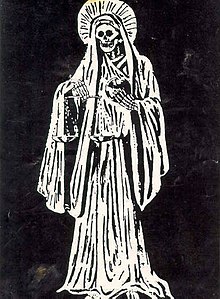

Mictlāntēcutli or Mictlantecuhtli, in Aztec mythology, is a god of the dead and the king of Mictlan (Chicunauhmictlan), the lowest and northernmost section of the underworld. He is one of the principal gods of the Aztecs and is the most prominent of several gods and goddesses of death and the underworld. The worship of Mictlantecuhtli sometimes involved ritual cannibalism, with human flesh being consumed in and around the temple. Other names given to Mictlantecuhtli include Ixpuztec, Nextepehua, and Tzontemoc.

Chamunda, also known as Chamundeshwari, Chamundi or Charchika, is a fearsome form of Chandi, the Hindu mother goddess, aka Shakti and is one of the seven Matrikas.

Jolly Roger is the traditional English name for the naval ensign flown to identify a pirate ship preceding or during an attack, during the early 18th century. The vast majority of such flags flew the motif of a human skull, or “Death's Head”, often accompanied by other elements, on a black, dark brown or dark blue field, sometimes called the “Death's Head flag” or just the “black flag”.

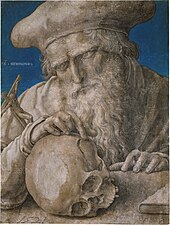

Vanitas is a genre of art which uses symbolism to show the transience of life, the futility of pleasure, and the certainty of death, and thus the vanity of ambition and all worldy desires. The paintings involved still life imagery of transitory items. The genre began in the 16th century and continued into the 17th century. Vanitas art is a type of allegorical art representing a higher ideal. It was a sub-genre of painting heavily employed by Dutch painters during the Baroque period (c.1585–1730). Spanish painters working at the end of the Spanish Golden Age also created vanitas paintings.

Et in Arcadia ego is a 1637–38 painting by Nicolas Poussin (1594–1665), the leading painter of the classical French Baroque style. It depicts a pastoral scene with idealized shepherds from classical antiquity, and a woman, possibly a shepherdess, gathered around an austere tomb that includes the Latin inscription "Et in Arcadia ego", which is translated to "Even in Arcadia, there am I" or "I too was in Arcadia". Poussin also painted another version of the subject in 1627 under the same title.

Memento mori is an artistic or symbolic trope acting as a reminder of the inevitability of death. The concept has its roots in the philosophers of classical antiquity and Christianity, and appeared in funerary art and architecture from the medieval period onwards.

A skull and crossbones is a symbol consisting of a human skull and two long bones crossed together under or behind the skull. The design originated in the Late Middle Ages as a symbol of death and especially as a memento mori on tombstones.

Symbols of death are the motifs, images and concepts associated with death throughout different cultures, religions and societies.

Totenkopf is the German word for skull. The word is often used to denote a figurative, graphic or sculptural symbol, common in Western culture, consisting of the representation of a human skull- usually frontal, more rarely in profile with or without the mandible. In some cases, other human skeletal parts may be added, often including two crossed long bones (femurs) depicted below or behind the skull. The human skull is an internationally used symbol for death, the defiance of death, danger, or the dead, as well as piracy or toxicity.

In various Asian religious traditions, the Nagas are a divine, or semi-divine, race of half-human, half-serpent beings that reside in the netherworld (Patala), and can occasionally take human or part-human form, or are so depicted in art. A female naga is called a Nagi, or a Nagini. Their descendents are known as Nagavanshi and Nair. According to legend, they are the children of the sage Kashyapa and Kadru. Rituals devoted to these supernatural beings have been taking place throughout South Asia for at least 2,000 years. They are principally depicted in three forms: as entirely human with snakes on the heads and necks, as common serpents, or as half-human, half-snake beings in Hinduism, Buddhism, and Jainism.

Nicolaes van Verendael or Nicolaes van Veerendael was a Flemish painter active in Antwerp who is mainly known for his flower paintings and vanitas still lifes. He was a frequent collaborator of other Antwerp artists to whose compositions he added the still life elements. He also painted a number of singeries, i.e., scenes with monkeys dressed and acting as humans.

The Capuchin Crypt is a small space comprising several tiny chapels located beneath the church of Santa Maria della Concezione dei Cappuccini on the Via Veneto near Piazza Barberini in Rome, Italy. It contains the skeletal remains of 3,700 bodies believed to be Capuchin friars buried by their order. The Catholic order insists that the display is not meant to be macabre, but a silent reminder of the swift passage of life on Earth and our own mortality.

Hendrick Andriessen, known as Mancken Heyn was a Flemish still-life painter. He is known for his vanitas still lifes, which are made up of objects referencing the precariousness of life, and 'smoker' still lifes, which depict smoking utensils. The artist worked in Antwerp and likely also in the Dutch Republic.

A kapala is a skull cup used as a ritual implement (bowl) in both Hindu Tantra and Buddhist Tantra (Vajrayana). Especially in Tibet, they are often carved or elaborately mounted with precious metals and jewels.

Brahmeswara Temple is a Hindu temple dedicated to Shiva located in Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India, erected at the end of the 9th century CE, is richly carved inside and out. This Hindu temple can be dated with fair accuracy by the use of inscriptions that were originally on the temple. They are now lost, but records of them preserve the information of around 1058 CE. The temple is built in the 18th regnal year of the Somavamsi king Udyotakesari by his mother Kolavati Devi, which corresponds to 1058 CE.

The skull and crossbones was a common fraternal motif as a symbol of mortality and warning in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The symbol was adopted, for various reasons, by many sporting teams, clubs, and societies in both America and Europe.

Baitāḷa deuḷa or Vaitāḷa deuḷa is an 8th-century Hindu temple of the typical Khakara style of the Kalinga architecture dedicated to Goddess Chamunda located in Bhubaneswar, the capital city of Odisha, India. It is also locally known as Tini-mundia deula due to the three spires on top of it, a very distinct and unusual feature. The three spires are believed to represent the three powers of the goddess Chamunda - Mahasaraswati, Mahalakshmi and Mahakali.

Pyramid of Skulls is a c. 1901 oil on canvas painting by French Post-Impressionist artist Paul Cézanne. It depicts four human skulls stacked in a pyramidal formation, a subject matter that increasingly preoccupied Cézanne in later life.