Project Stormfury was an attempt to weaken tropical cyclones by flying aircraft into them and seeding with silver iodide. The project was run by the United States Government from 1962 to 1983. The hypothesis was that the silver iodide would cause supercooled water in the storm to freeze, disrupting the inner structure of the hurricane, and this led to seeding several Atlantic hurricanes. However, it was later shown that this hypothesis was incorrect. It was determined that most hurricanes do not contain enough supercooled water for cloud seeding to be effective. Additionally, researchers found that unseeded hurricanes often undergo the same structural changes that were expected from seeded hurricanes. This finding called Stormfury's successes into question, as the changes reported now had a natural explanation.

The Lockheed WP-3D Orion is a highly modified P-3 Orion used by the Aircraft Operations Center division of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Only two of these aircraft exist, each incorporating numerous features for the role of collecting weather information. During the Atlantic hurricane season, the WP-3Ds are deployed for duty as hurricane hunters. The aircraft also support research on other topics, such as Arctic ice coverage, air chemistry studies, and ocean water temperature and current analysis.

The Lockheed WC-130 is a high-wing, medium-range aircraft used for weather reconnaissance missions by the United States Air Force. The aircraft is a modified version of the C-130 Hercules transport configured with specialized weather instrumentation including a dropsonde deployment/receiver system and crewed by a meteorologist for penetration of tropical cyclones and winter storms to obtain data on movement, size and intensity.

The 53rd Weather Reconnaissance Squadron, also known by its nickname, Hurricane Hunters, is a flying unit of the United States Air Force, and "the only Department of Defense organization still flying into tropical storms and hurricanes." Aligned under the 403rd Wing of the Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC) and based at Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi, with ten aircraft, it flies into tropical cyclones in the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean Sea, the Gulf of Mexico and the Central Pacific Ocean for the specific purpose of directly measuring weather data in and around those storms. The 53rd WRS currently operates the Lockheed WC-130J aircraft as its weather data collection platform.

Keesler Air Force Base is a United States Air Force base located in Biloxi, a city along the Gulf Coast in Harrison County, Mississippi, United States. The base is named in honor of aviator 2d Lt Samuel Reeves Keesler Jr., a Mississippi native killed in France during the First World War. The base is home of Headquarters, Second Air Force and the 81st Training Wing of the Air Education and Training Command (AETC).

A dropsonde is an expendable weather reconnaissance device created by the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR), designed to be dropped from an aircraft at altitude over water to measure storm conditions as the device falls to the surface. The sonde contains a GPS receiver, along with pressure, temperature, and humidity (PTH) sensors to capture atmospheric profiles and thermodynamic data. It typically relays this data to a computer in the aircraft by radio transmission.

The Lockheed EC-121 Warning Star was an American airborne early warning and control radar surveillance aircraft operational in the 1950s in both the United States Navy (USN) and United States Air Force (USAF).

The Consolidated PB4Y-2 Privateer is an American World War II and Korean War era patrol bomber of the United States Navy derived from the Consolidated B-24 Liberator. The Navy had been using B-24s with only minor modifications as the PB4Y-1 Liberator, and along with maritime patrol Liberators used by RAF Coastal Command this type of patrol plane was proven successful. A fully navalised design was desired, and Consolidated developed a dedicated long-range patrol bomber in 1943, designated PB4Y-2 Privateer. In 1951, the type was redesignated P4Y-2 Privateer. A further designation change occurred in September 1962, when the remaining Navy Privateers were redesignated QP-4B.

The 1971 Pacific hurricane season began on May 15, 1971 in the eastern Pacific, and on June 1, 1971 in the Central Pacific ; both ended on November 30, 1971. These dates, adopted by convention, historically describe the period in each year when most tropical cyclogenesis occurs in these regions of the Pacific. It was the first year that continuous Weather satellite coverage existed over the entire Central Pacific. As such, this season is often viewed as the start year for modern reliable tropical cyclone data in the Pacific Ocean.

Typhoon Bess, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Susang, was responsible for the disappearance of a United States Air Force weather reconnaissance aircraft. Developing out of a poorly organized system on October 8 to the east of the Philippines, Bess featured two centers of circulation. Initially the southern low was monitored; however, a low to the north soon became the dominant center. Tracking generally west-northwestward, the storm gradually intensified before striking northern Luzon as a minimal typhoon on October 11. Temporary weakening took place due to interaction with land. After moving back over water the following morning, Bess regained typhoon intensity. This was short-lived though, as conditions surrounding the cyclone soon caused it to weaken. Now moving due west, the weakening storm eventually struck Hainan Island as a tropical storm on October 12 before diminishing to a tropical depression. The depression briefly moved back over water before dissipating in northern Vietnam on October 14.

Tropical cyclone observation has been carried out over the past couple of centuries in various ways. The passage of typhoons, hurricanes, as well as other tropical cyclones have been detected by word of mouth from sailors recently coming to port or by radio transmissions from ships at sea, from sediment deposits in near shore estuaries, to the wiping out of cities near the coastline. Since World War II, advances in technology have included using planes to survey the ocean basins, satellites to monitor the world's oceans from outer space using a variety of methods, radars to monitor their progress near the coastline, and recently the introduction of unmanned aerial vehicles to penetrate storms. Recent studies have concentrated on studying hurricane impacts lying within rocks or near shore lake sediments, which are branches of a new field known as paleotempestology. This article details the various methods employed in the creation of the hurricane database, as well as reconstructions necessary for reanalysis of past storms used in projects such as the Atlantic hurricane reanalysis.

The Hurricane Research Division (HRD) is a section of the Atlantic Oceanographic and Meteorological Laboratory (AOML) in Miami, Florida, and is the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) focus for tropical cyclone research. The thirty member division is not a part of the National Hurricane Center but cooperates closely with them in carrying out its annual field program and in transitioning research results into operational tools for hurricane forecasters. HRD was formed from the National Hurricane Research Laboratory in 1984, when it was transferred to AOML and unified with the oceanographic laboratories.

The 920th Rescue Wing is part of the Air Reserve Component (ARC) of the United States Air Force. The wing is assigned to the Tenth Air Force of the Air Force Reserve Command (AFRC).

The NOAA Hurricane Hunters are a group of aircraft used for hurricane reconnaissance by the United States National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). They fly through hurricanes to help forecasters and scientists gather operational and research data. The crews also conduct other research projects including ocean wind studies, winter storm research, thunderstorm research, coastal erosion, and air chemistry flights.

The 403rd Operations Group is the operational flying component of the United States Air Force Reserve 403rd Wing. It is stationed at Keesler Air Force Base, Mississippi.

The 55th Space Weather Squadron is an inactive United States Air Force unit. It was last assigned to the 50th Operations Group at Schriever Air Force Base, Colorado, where it was inactivated on 16 July 2002.

The 54th Weather Reconnaissance Squadron is an inactive United States Air Force unit. Its last assignment was to the 41st Rescue and Weather Reconnaissance Wing at Andersen Air Force Base, Guam, where it was inactivated on 30 September 1987.

Weather reconnaissance is the acquisition of weather data used for research and planning. Typically the term reconnaissance refers to observing weather from the air, as opposed to the ground.

Typhoon Nora, known in the Philippines as Typhoon Luming, was tied for the fourth-most intense tropical cyclone on record. Originating from an area of low pressure over the western Pacific, Nora was first identified as a tropical depression on October 2, 1973. Tracking generally westward, the system gradually intensified, attaining typhoon status the following evening. After turning northwestward, the typhoon underwent a period of rapid intensification, during which its central pressure decreased by 77 mb in 24 hours. At the end of this phase, Nora peaked with winds of 295 km/h (185 mph) and a pressure of 875 mb, making it the most-intense tropical cyclone on record at the time; however, this pressure has since been surpassed by Typhoon June, Typhoon Tip and Hurricane Patricia. The typhoon subsequently weakened and turned northwestward as it approached the Philippines. After brushing Luzon on October 7, the system passed south of Taiwan and ultimately made landfall in China on October 10. Once onshore, Nora quickly weakened and dissipated the following day.

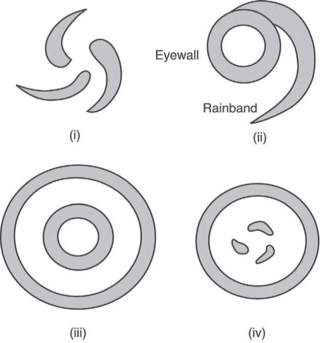

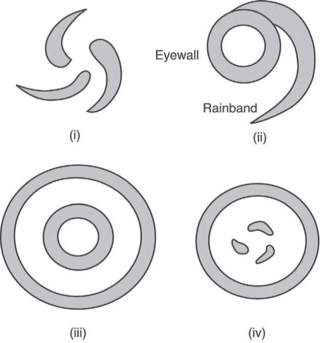

The Hurricane Rainband and Intensity Change Experiment (RAINEX) is a project to improve hurricane intensity forecasting via measuring interactions between rainbands and the eyewalls of tropical cyclones. The experiment was planned for the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season. This coincidence of RAINEX with the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season led to the study and exploration of infamous hurricanes Katrina, Ophelia, and Rita. Where Hurricane Katrina and Hurricane Rita would go on to cause major damage to the US Gulf coast, Hurricane Ophelia provided an interesting contrast to these powerful cyclones as it never developed greater than a Category 1.