The Roman calendar was the calendar used by the Roman Kingdom and Roman Republic. Although the term is primarily used for Rome's pre-Julian calendars, it is often used inclusively of the Julian calendar established by the reforms of the Dictator Julius Caesar and Emperor Augustus in the late 1st century BC.

The Ides of March is the 74th day in the Roman calendar, corresponding to 15 March. It was marked by several religious observances and was a deadline for settling debts in Rome. In 44 BC, it became notorious as the date of the assassination of Julius Caesar, which made the Ides of March a turning point in Roman history.

A religious festival is a time of special importance marked by adherents to that religion. Religious festivals are commonly celebrated on recurring cycles in a calendar year or lunar calendar. The science of religious rites and festivals is known as heortology.

In the ancient Roman calendar, Quintilis or Quinctilis was the month following Junius (June) and preceding Sextilis (August). Quintilis is Latin for "fifth": it was the fifth month in the earliest calendar attributed to Romulus, which began with Martius and had 10 months. After the calendar reform that produced a 12-month year, Quintilis became the seventh month, but retained its name. In 45 BC, Julius Caesar instituted a new calendar that corrected astronomical discrepancies in the old. After his death in 44 BC, the month of Quintilis, his birth month, was renamed Julius in his honor, hence July.

Sextilis or mensis Sextilis was the Latin name for what was originally the sixth month in the Roman calendar, when March was the first of ten months in the year. After the calendar reform that produced a twelve-month year, Sextilis became the eighth month, but retained its name. It was renamed Augustus (August) in 8 BC in honor of the first Roman emperor, Augustus. Sextilis followed Quinctilis, which was renamed Julius (July) after Julius Caesar, and preceded September, which was originally the seventh month.

Festivals in ancient Rome were a very important part in Roman religious life during both the Republican and Imperial eras, and one of the primary features of the Roman calendar. Feriae were either public (publicae) or private (privatae). State holidays were celebrated by the Roman people and received public funding. Games (ludi), such as the Ludi Apollinares, were not technically feriae, but the days on which they were celebrated were dies festi, holidays in the modern sense of days off work. Although feriae were paid for by the state, ludi were often funded by wealthy individuals. Feriae privatae were holidays celebrated in honor of private individuals or by families. This article deals only with public holidays, including rites celebrated by the state priests of Rome at temples, as well as celebrations by neighborhoods, families, and friends held simultaneously throughout Rome.

The calends or kalends is the first day of every month in the Roman calendar. The English word "calendar" is derived from this word.

Februarius, fully Mensis Februarius, was the shortest month of the Roman calendar from which the Julian and Gregorian month of February derived. It was eventually placed second in order, preceded by Ianuarius and followed by Martius. In the oldest Roman calendar, which the Romans believed to have been instituted by their legendary founder Romulus, March was the first month, and the calendar year had only ten months in all. Ianuarius and Februarius were supposed to have been added by Numa Pompilius, the second king of Rome, originally at the end of the year. It is unclear when the Romans reset the course of the year so that January and February came first.

The Acta Triumphorum or Triumphalia, better known as the Fasti Triumphales, or Triumphal Fasti, is a calendar of Roman magistrates honoured with a celebratory procession known as a triumphus, or triumph, in recognition of an important military victory, from the earliest period down to 19 BC. Together with the related Fasti Capitolini and other, similar inscriptions found at Rome and elsewhere, they form part of a chronology referred to by various names, including the Fasti Annales or Historici, Fasti Consulares, or Consular Fasti, and frequently just the fasti.

Maius or mensis Maius (May) was the third month of the ancient Roman calendar, following Aprilis (April) and preceding Iunius (June). On the oldest Roman calendar that had begun with March, it was the third of ten months in the year. May had 31 days.

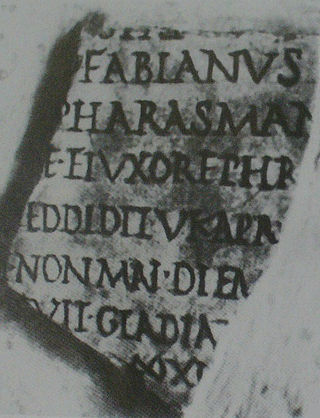

The Fasti Ostienses are a calendar of Roman magistrates and significant events from 49 BC to AD 175, found at Ostia, the principal seaport of Rome. Together with similar inscriptions, such as the Fasti Capitolini and Fasti Triumphales at Rome, the Fasti Ostienses form part of a chronology known as the Fasti Consulares, or Consular Fasti.

Martius or mensis Martius ("March") was the first month of the ancient Roman year until possibly as late as 153 BC. After that time, it was the third month, following Februarius (February) and preceding Aprilis (April). Martius was one of the few Roman months named for a deity, Mars, who was regarded as an ancestor of the Roman people through his sons Romulus and Remus.

Aprilis or mensis Aprilis (April) was the second month of the ancient Roman calendar, following Martius (March) and preceding Maius (May). On the oldest Roman calendar that had begun with March, Aprilis was the second of ten months in the year. April had 29 days on calendars of the Roman Republic, with a day added to the month during the reform in the mid-40s BC that produced the Julian calendar.

On the ancient Roman calendar, mensis Iunius or Iunius, also Junius (June), was the fourth month, following Maius (May). In the oldest calendar attributed by the Romans to Romulus, Iunius was the fourth month in a ten-month year that began with March (Martius, "Mars' month"). The month following June was thus called Quinctilis or Quintilis, the "fifth" month. Iunius had 29 days until a day was added during the Julian reform of the calendar in the mid-40s BC. The month that followed Iunius was renamed Iulius (July) in honour of Julius Caesar.

September or mensis September was originally the seventh of ten months on the ancient Roman calendar that began with March. It had 29 days. After the reforms that resulted in a 12-month year, September became the ninth month, but retained its name. September followed what was originally Sextilis, the "sixth" month, renamed Augustus in honor of the first Roman emperor, and preceded October, the "eighth" month that like September retained its numerical name contrary to its position on the calendar. A day was added to September in the mid-40s BC as part of the Julian calendar reform.

October or mensis October was the eighth of ten months on the oldest Roman calendar. It had 31 days. October followed September and preceded November. After the calendar reform that resulted in a 12-month year, October became the tenth month, but retained its numerical name, as did the other months from September to December.

November or mensis November was originally the ninth of ten months on the Roman calendar, following October and preceding December. It had 29 days. In the reform that resulted in a 12-month year, November became the eleventh month, but retained its name, as did the other months from September through December. A day was added to November during the Julian calendar reform in the mid-40s BC.

December or mensis December was originally the tenth month of the Roman calendar, following November and preceding Ianuarius. It had 29 days. When the calendar was reformed to create a 12-month year starting in Ianuarius, December became the twelfth month, but retained its name, as did the other numbered months from Quintilis (July) to December. Its length was increased to 31 days under the Julian calendar reform.

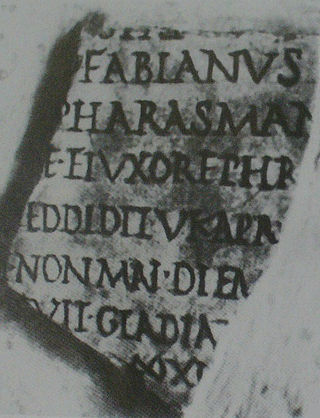

The Fasti Potentini are a fragmentary list of Roman consuls from AD 86 to 118, originally erected at Potentia in Lucania, a region of southern Italy. Together with similar inscriptions, such as the Fasti Capitolini and Fasti Triumphales, as well as the names of magistrates mentioned by ancient writers, the Potentini form part of a chronology referred to as the Fasti Consulares, or Consular Fasti, sometimes abbreviated to just "the fasti".