Related Research Articles

The Akkadian Empire was the first ancient empire of Mesopotamia, succeeding the long-lived civilization of Sumer. Centered on the city of Akkad and its surrounding region, the empire would unite Akkadian and Sumerian speakers under one rule and exercised significant influence across Mesopotamia, the Levant, and Anatolia, sending military expeditions as far south as Dilmun and Magan in the Arabian Peninsula.

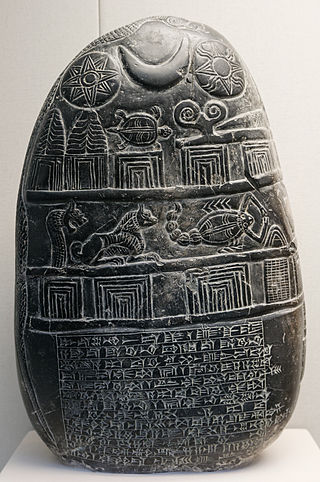

Sin or Suen (Akkadian: 𒀭𒂗𒍪, dEN.ZU) also known as Nanna (Sumerian: 𒀭𒋀𒆠DŠEŠ.KI, DNANNA) was the Mesopotamian god representing the moon. While these two names originate in two different languages, respectively Akkadian and Sumerian, they were already used interchangeably to refer to one deity in the Early Dynastic period. They were sometimes combined into the double name Nanna-Suen. A third well attested name is Dilimbabbar (𒀭𒀸𒁽𒌓). Additionally, the moon god could be represented by logograms reflecting his lunar character, such as d30 (𒀭𒌍), referring to days in the lunar month or dU4.SAKAR (𒀭𒌓𒊬), derived from a term referring to the crescent. In addition to his astral role, Sin was also closely associated with cattle herding. Furthermore, there is some evidence that he could serve as a judge of the dead in the underworld. A distinct tradition in which he was regarded either as a god of equal status as the usual heads of the Mesopotamian pantheon, Enlil and Anu, or as a king of the gods in his own right, is also attested, though it only had limited recognition. In Mesopotamian art, his symbol was the crescent. When depicted anthropomorphically, he typically either wore headwear decorated with it or held a staff topped with it, though on kudurru the crescent alone served as a representation of him. He was also associated with boats.

Ningal was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as the wife of the moon god, Nanna/Sin. She was particularly closely associated with his main cult centers, Ur and Harran, but they were also worshiped together in other cities of Mesopotamia. She was particularly venerated by the Third Dynasty of Ur and later by kings of Larsa.

Naram-Sin, also transcribed Narām-Sîn or Naram-Suen, was a ruler of the Akkadian Empire, who reigned c. 2254–2218 BC, and was the third successor and grandson of King Sargon of Akkad. Under Naram-Sin the empire reached its maximum extent. He was the first Mesopotamian king known to have claimed divinity for himself, taking the title "God of Akkad", and the first to claim the title "King of the Four Quarters". He became the patron city god of Akkade as Enlil was in Nippur. His enduring fame resulted in later rulers, Naram-Sin of Eshnunna and Naram-Sin of Assyria as well as Naram-Sin of Uruk, assuming the name.

Zababa was the tutelary deity of the city of Kish in ancient Mesopotamia. He was a war god. While he was regarded as similar to Ninurta and Nergal, he was never fully conflated with them. His worship is attested from between the Early Dynastic to Achaemenid periods, with the Old Babylonian kings being particularly devoted to him. Starting with the Old Babylonian period, he was regarded as married to the goddess Bau.

Ishara (Išḫara) was a goddess originally worshipped in Ebla and other nearby settlements in the north of modern Syria in the third millennium BCE. The origin of her name is disputed, and due to lack of evidence supporting Hurrian or Semitic etymologies it is sometimes assumed it might have originated in a linguistic substrate. In Ebla, she was considered the tutelary goddess of the royal family. An association between her and the city is preserved in a number of later sources from other sites as well. She was also associated with love, and in that role is attested further east in Mesopotamia as well. Multiple sources consider her the goddess of the institution of marriage, though she could be connected to erotic love as well, as evidenced by incantations. She was also linked to oaths and divination. She was associated with reptiles, especially mythical bašmu and ḫulmiẓẓu, and later on with scorpions as well, though it is not certain how this connection initially developed. In Mesopotamian art from the Kassite and Middle Babylonian periods she was only ever represented through her scorpion symbol rather than in anthropomorphic form. She was usually considered to be an unmarried and childless goddess, and she was associated with various deities in different time periods and locations. In Ebla, the middle Euphrates area and Mesopotamia she was closely connected with Ishtar due to their similar character, though they were not necessarily regarded as identical. In the Ur III period, Mesopotamians associated her with Dagan due to both of them being imported to Ur from the west. She was also linked to Ninkarrak. In Hurrian tradition she developed an association with Allani.

Ištaran was a Mesopotamian god who was the tutelary deity of the city of Der, a city-state located east of the Tigris, in the proximity of the borders of Elam. It is known that he was a divine judge, and his position in the Mesopotamian pantheon was most likely high, but much about his character remains uncertain. He was associated with snakes, especially with the snake god Nirah, and it is possible that he could be depicted in a partially or fully serpentine form himself. He is first attested in the Early Dynastic period in royal inscriptions and theophoric names. He appears in sources from the reign of many later dynasties as well. When Der attained independence after the Ur III period, local rulers were considered representatives of Ištaran. In later times, he retained his position in Der, and multiple times his statue was carried away by Assyrians to secure the loyalty of the population of the city.

Nanaya was a Mesopotamian goddess of love, closely associated with Inanna.

Pabilsaĝ was a Mesopotamian god. Not much is known about his role in Mesopotamian religion, though it is known that he could be regarded as a bow-armed warrior deity, as a divine cadastral officer or a judge. He might have also been linked to healing, though this remains disputed. In his astral aspect, first attested in the Old Babylonian period, he was a divine representation of the constellation Sagittarius.

Papsukkal (𒀭𒉽𒈛) was a Mesopotamian god regarded as the sukkal of Anu and his wife Antu in Seleucid Uruk. In earlier periods he was instead associated with Zababa. He acquired his new role through syncretism with Ninshubur.

Kakka was a Mesopotamian god best known as the sukkal of Anu and Anshar. His cult center was Maškan-šarrum, most likely located in the north of modern Iraq on the banks of the Tigris.

Shullat (Šûllat) and Hanish (Ḫaniš) were a pair of Mesopotamian gods. They were usually treated as inseparable, and appear together in various works of literature. Their character was regarded as warlike and destructive, and they were associated with the weather.

Tishpak (Tišpak) was a Mesopotamian god associated with the ancient city Eshnunna and its sphere of influence, located in the Diyala area of Iraq. He was primarily a war deity, but he was also associated with snakes, including the mythical mushussu and bashmu, and with kingship.

Akkad was the capital of the Akkadian Empire, which was the dominant political force in Mesopotamia during a period of about 150 years in the last third of the 3rd millennium BC.

Ninsianna was a Mesopotamian deity considered to be the personification of Venus. This theonym also served as the name of the planet in astronomical texts until the end of the Old Babylonian period. There is evidence that Ninsianna's gender varied between locations, and both feminine and masculine forms of this deity were worshiped. Due to their shared connection to Venus, Ninsianna was associated with Inanna. Furthermore, the deity Kabta appears alongside Ninsianna in many texts, but the character of the relation between them remains uncertain.

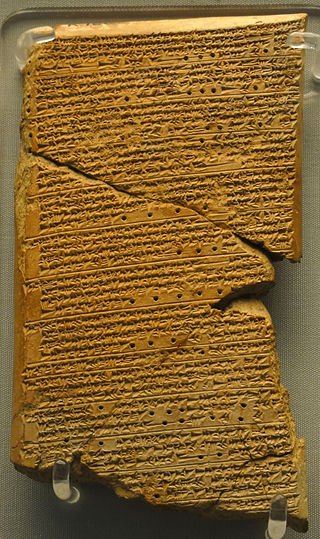

Akkadian or Mesopotamian royal titulary refers to the royal titles and epithets assumed by monarchs in Ancient Mesopotamia from the Akkadian period to the fall of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, with some scant usage in the later Achaemenid and Seleucid periods. The titles and the order they were presented in varied from king to king, with similarities between kings usually being because of a king's explicit choice to align himself with a predecessor. Some titles, like the Akkadian šar kibrāt erbetti and šar kiššatim and the Neo-Sumerian šar māt Šumeri u Akkadi would remain in use for more than a thousand years through several different empires and others were only used by a single king.

Laṣ was a Mesopotamian goddess who was commonly regarded as the wife of Nergal, a god associated with war and the underworld. Instances of both conflation and coexistence of her and another goddess this position was attributed to, Mammitum, are attested in a number sources. Her cult centers were Kutha in Babylonia and Tarbiṣu in Assyria.

Belet-Šuḫnir and Belet-Terraban were a pair of Mesopotamian goddesses best known from the archives of the Third Dynasty of Ur, but presumed to originate further north, possibility in the proximity of modern Kirkuk and ancient Eshnunna. Their names are usually assumed to be derived from cities where they were originally worshiped. Both in ancient sources, such as ritual texts, seal inscriptions and god lists, and in modern scholarship, they are typically treated as a pair. In addition to Ur and Eshnunna, both of them are also attested in texts from Susa in Elam. Their character remains poorly understood due to scarcity of sources, though it has been noted that the tone of many festivals dedicated to them was "lugubrious," which might point at an association with the underworld.

Ulmašītum was a Mesopotamian goddess regarded as warlike. Her name was derived from (E-)Ulmaš, a temple in the city of Akkad dedicated to Ishtar. She was commonly associated with Annunitum, and in many texts they appear as a pair. While she originated in northern Mesopotamia, in the Ur III period she is best attested in Ur, though later she was also worshiped in Malgium.

Lugal-Marada was a Mesopotamian god who served as the tutelary deity of the city of Marad. His wife was Imzuanna. He was seemingly conflated with another local god, Lulu. There is also evidence that he could be viewed as a manifestation of Ninurta. He had a temple in Marad, the Eigikalamma, and additionally appears in Old Babylonian oath formulas from this city.

References

- 1 2 3 4 Pardee 2000, p. 187.

- 1 2 3 4 Krebernik 2016, p. 393.

- ↑ Krebernik 2016, p. 392.

- ↑ Nowicki 2016, p. 70.

- 1 2 3 Such-Gutiérrez 2005, p. 18.

- 1 2 George 1992, p. 310.

- 1 2 Zsolnay 2013, p. 94.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Krebernik 2016, p. 396.

- ↑ Nowicki 2016, pp. 67–68.

- ↑ Wang 2011, p. 197.

- 1 2 3 4 Nowicki 2016, p. 68.

- ↑ Krebernik 2016, pp. 395–396.

- ↑ Sasson 2001, p. 413.

- ↑ Healey 1999, p. 447.

- ↑ Pardee 2000, p. 297.

- ↑ Krebernik 2016, p. 397.

- 1 2 Nakata 2011, p. 132.

- ↑ Foster 1996, p. 55.

- ↑ Foster 1996, p. 56.

- ↑ Potts 1999, p. 111.

- 1 2 Zadok 2018, p. 150.

- ↑ Foster 1996, p. 115.

- 1 2 Beaulieu 2017, p. 50.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 165.

- ↑ Beaulieu 2017, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Suter 2007, p. 320.

- 1 2 Steinkeller 2018, p. 199.

- 1 2 Foster 1996, p. 61.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Krebernik 2016, p. 394.

- ↑ Nakata 1995, p. 252.

- ↑ Nowicki 2016, p. 73.

- ↑ Frayne 1990, p. 556.

- ↑ Frayne 1990, p. 150.

- ↑ Podany 2014, pp. 60–61.

- ↑ Beckman 2002, p. 40.

- ↑ Beckman 2002, p. 50.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 40.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 75.

- ↑ George 1993, p. 41.

- ↑ George 1993, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Krebernik 2016, pp. 394–395.

- ↑ Krebernik 2016, p. 395.

- ↑ Foster 1996, p. 108.

- ↑ Foster 1996, p. 109.

- ↑ Foster 1996, p. 110.

- ↑ Foster 1996, p. 264.

Bibliography

- Beaulieu, Paul-Alain (2017). A History of Babylon, 2200 BC - AD 75. Blackwell History of the Ancient World. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-119-45907-1 . Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- Beckman, Gary (2002). "The Pantheon of Emar". Silva Anatolica: Anatolian studies presented to Maciej Popko on the occasion of his 65th birthday. Warsaw: Agade. hdl:2027.42/77414. ISBN 83-87111-12-0. OCLC 51004996.

- Foster, Benjamin (1996). Before the muses: an anthology of Akkadian literature. Potomac, MD: CDL Press. ISBN 1-883053-23-4. OCLC 34149948.

- Frayne, Douglas (1990). Old Babylonian Period (2003-1595 B.C.). University of Toronto Press. doi:10.3138/9781442678033. ISBN 978-1-4426-7803-3.

- George, Andrew R. (1992). Babylonian Topographical Texts. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. Departement Oriëntalistiek. ISBN 978-90-6831-410-6 . Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- George, Andrew R. (1993). House most high: the temples of ancient Mesopotamia. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns. ISBN 0-931464-80-3. OCLC 27813103.

- Healey, John F. (1999), "Ilib", in van der Toorn, Karel; Becking, Bob; van der Horst, Pieter W. (eds.), Dictionary of Deities and Demons in the Bible, Eerdmans Publishing Company, ISBN 978-0-8028-2491-2 , retrieved 2022-08-28

- Krebernik, Manfred (2016), "Ilaba", Reallexikon der Assyriologie (in German), retrieved 2022-08-28

- Nakata, Ichiro (1995). "A Study of Women's Theophoric Personal Names in Old Babylonian Texts from Mari". Orient. The Society for Near Eastern Studies in Japan. 30 and 31: 234–253. doi:10.5356/orient1960.30and31.234. ISSN 1884-1392.

- Nakata, Ichiro (2011). "The God Itūr-Mēr in the Middle Euphrates Region During the Old Babylonian Period". Revue d'Assyriologie et d'archéologie orientale. Presses Universitaires de France. 105: 129–136. doi: 10.3917/assy.105.0129 . ISSN 0373-6032. JSTOR 42580244. S2CID 194094468.

- Nowicki, Stefan (2016). "Sargon of Akkade and his God". Acta Orientalia Academiae Scientiarum Hungaricae. Akadémiai Kiadó. 69 (1): 63–82. doi:10.1556/062.2016.69.1.4. ISSN 0001-6446. JSTOR 43957458 . Retrieved 2022-08-28.

- Pardee, Dennis (2000). Les textes rituels d'Ougarit (PDF). Ras Shamra – Ougarit (in French). Vol. XII. Paris: Éditions Recherche sur les Civilisations. ISBN 978-2-86538-276-7 . Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- Podany, Amanda H. (2014). "Hana and the Low Chronology". Journal of Near Eastern Studies. University of Chicago Press. 73 (1): 49–71. doi:10.1086/674706. ISSN 0022-2968. S2CID 161187934.

- Potts, Daniel T. (1999). The Archaeology of Elam. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/cbo9780511489617. ISBN 978-0-521-56358-1.

- Sasson, Jack M. (2001). "Ancestors Divine?" (PDF). In van Soldt, Wilfred H.; Dercksen, Jan G.; Kouwenberg, N. J. C.; Krispijn, Theo (eds.). Veenhof Anniversary Volume: Studies Presented to Klaas R. Veenhof on the Occasion of His Sixty-fifth Birthday. Pihans Series. Nederlands Instituut voor het Nabije Oosten. ISBN 978-90-6258-091-0 . Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- Steinkeller, Piotr (2018). "The Birth of Elam in History". The Elamite world. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-1-315-65803-2. OCLC 1022561448.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Such-Gutiérrez, Marcos (2005). "Untersuchungen zum Pantheon von Adab im 3. Jt". Archiv für Orientforschung (in German). Archiv für Orientforschung (AfO)/Institut für Orientalistik. 51: 1–44. ISSN 0066-6440. JSTOR 41670228 . Retrieved 2022-08-27.

- Suter, Claudia E. (2007). "Between Human and Divine: High Priestesses in Images from the Akkad to the Isin-Larsa Period". In Winter, Irene; Cheng, Jack; Feldman, Marian H. (eds.). Ancient Near Eastern art in context: studies in honor of Irene J. Winter. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 978-90-474-2085-9. OCLC 648616171.

- Wang, Xianhua (2011). The metamorphosis of Enlil in early Mesopotamia. Münster. ISBN 978-3-86835-052-4. OCLC 712921671.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Zadok, Ran (2018). "The Peoples of Elam". The Elamite world. Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-1-315-65803-2. OCLC 1022561448.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Zsolnay, Ilona (2013). "The Misconstrued Role of the Assinnu in Ancient Near Eastern Prophecy". Prophets Male and Female: Gender and Prophecy in the Hebrew Bible, the Eastern Mediterranean and the Ancient Near East. SBL Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt16wdmbj.8.