The Bharatiya Janata Party is a political party in India and one of the two major Indian political parties alongside the Indian National Congress. Since 2014, it has been the ruling political party in India under the incumbent Prime Minister Narendra Modi. The BJP is aligned with right-wing politics and has close ideological and organisational links to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) volunteer paramilitary organisation. Its policies adhere to Hindutva, a Hindu nationalist ideology. As of January 2024, it is the country's biggest political party in terms of representation in the Parliament of India as well as state legislatures.

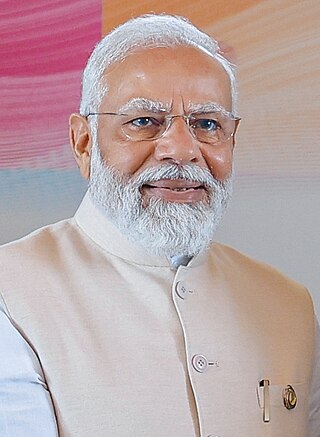

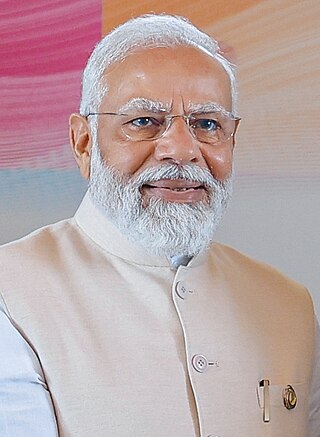

Narendra Damodardas Modi is an Indian politician who has served as the 14th prime minister of India since May 2014. Modi was the chief minister of Gujarat from 2001 to 2014 and is the Member of Parliament (MP) for Varanasi. He is a member of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a right wing Hindu nationalist paramilitary volunteer organisation. He is the longest-serving prime minister from outside the Indian National Congress.

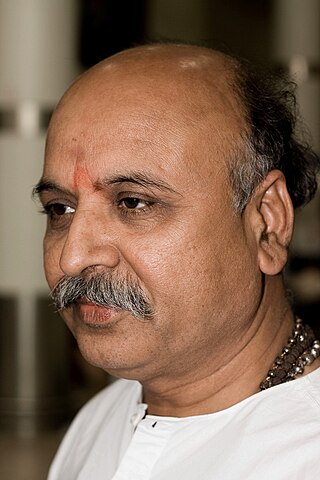

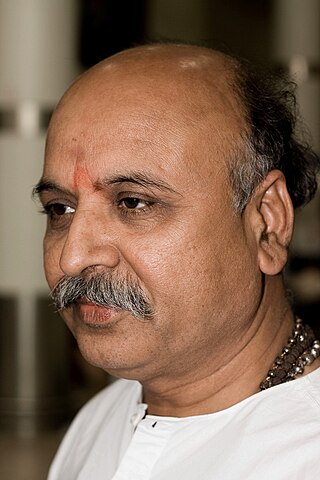

Pravin Togadia is an Indian doctor, cancer surgeon and an advocate for Hindu nationalism, coming from the state of Gujarat. He was the former International Working President of the Vishva Hindu Parishad (VHP) and a cancer surgeon by qualification. He is Founder and Current President of Antarashtriya Hindu Parishad. He had a falling out with the Sangh Parivar and is a vocal critic of Narendra Modi.

The Godhra train burning occurred on the morning of 27 February 2002: 59 Hindu pilgrims and karsevaks returning from Ayodhya were killed in a fire inside the Sabarmati Express near the Godhra railway station in the Indian state of Gujarat. The cause of the fire remains disputed. The Gujarat riots, in which Muslims were the targets of widespread and severe violence, occurred shortly afterward.

The 2002 Gujarat riots, also known as the 2002 Gujarat violence, was a three-day period of inter-communal violence in the western Indian state of Gujarat. The burning of a train in Godhra on 27 February 2002, which caused the deaths of 58 Hindu pilgrims and karsevaks returning from Ayodhya, is cited as having instigated the violence. Following the initial riot incidents, there were further outbreaks of violence in Ahmedabad for three months; statewide, there were further outbreaks of violence against the minority Muslim population of Gujarat for the next year.

Final Solution is a 2004 documentary film directed by Rakesh Sharma concerning the 2002 Gujarat riots in the state of Gujarat in which 254 Hindus and 790 Muslims were killed. Hindu right wing organizations were made responsible for these riots which took place as a "spontaneous response" to the killing of 70 Hindu Pilgrims in the Godhra Train Burning by a mob of radical muslims on 27 February 2002. But as the film proceeds with victims continuing to come forward and share their experiences, a more unsettling possibility seems to emerge- that far from being a spontaneous expression of outrage. The makers of the film claim that the violence had been carefully coordinated and planned.

Religious violence in India includes acts of violence by followers of one religious group against followers and institutions of another religious group, often in the form of rioting. Religious violence in India has generally involved Hindus and Muslims.

Atal Bihari Vajpayee was an Indian politician who served twice as Prime Minister of India, first from 16 May to 1 June 1996, and then from 19 March 1998 to 22 May 2004. A member of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), Vajpayee was the tenth Prime Minister. He headed the BJP-led National Democratic Alliance in the Indian Parliament, and became the first Prime Minister unaffiliated with the Indian National Congress to complete a full five-year term in office. He died at the age of 93 on Thursday 16 August 2018 at 17:05 at AIIMS, New Delhi.

Amit Anil Chandra Shah is an Indian politician who is currently serving as the 31st Minister of Home Affairs since 2019 and the 1st Minister of Co-operation of India since 2021. He served as the 10th President of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) from 2014 to 2020. He has also served as chairman of the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) since 2014. He was elected to the lower house of Parliament, Lok Sabha, in the 2019 Indian general elections from Gandhinagar. Earlier, he had been elected as a member of the upper house of Parliament, Rajya Sabha, from Gujarat from 2017 to 2019.

Sanjiv Bhatt is a former Indian Police Service officer of the Gujarat-cadre. He is known for his role in filing an affidavit in the Supreme Court of India against the then Chief Minister of the Government of Gujarat, Narendra Modi, concerning Modi's alleged role in the 2002 Gujarat riots. He claimed to have attended a meeting, during which Modi allegedly asked top police officials to let Hindus vent their anger against the Muslims. However, the Special Investigation Team appointed by the Supreme Court of India concluded that Bhatt did not attend any such meeting, and dismissed his allegations.

The Naroda Patiya massacre took place on 28 February 2002 at Naroda, in Ahmedabad, India, during the 2002 Gujarat riots. 97 Muslims were killed by a mob of approximately 5,000 people, organised by the Bajrang Dal, a wing of the Vishva Hindu Parishad, and allegedly supported by the Bharatiya Janata Party which was in power in the Gujarat State Government. The massacre at Naroda occurred during the bandh (strike) called by Vishwa Hindu Parishad a day after the Godhra train burning. The riot lasted over 10 hours, during which the mob plundered, stabbed, sexually assaulted, gang-raped and burnt people individually and in groups. After the conflict, a curfew was imposed in the state and Indian Army troops were called in to contain further violence.

The Truth: Gujarat 2002 was an investigative report on the 2002 Gujarat riots published by India's Tehelka news magazine in its 7 November 2007 issue. The video footage was screened by the news channel Aaj Tak. The report, based on a six-month-long investigation and involving video sting operations, stated that the violence was made possible by the support of the state police and the then Chief Minister of Gujarat Narendra Modi for the perpetrators. The report and the reactions to it were widely covered in Indian and international media. The recordings were authenticated by India's Central Bureau of Investigation on 10 May 2009.

The Indian general election of 2014 were held to constitute the 16th Lok Sabha in India. Voting took place in all 543 parliamentary constituencies of India to elect members of parliament in the Lok Sabha. The result of this election was declared on 16 May. The 15th Lok Sabha completed its constitutional mandate on 31 May 2014. Since the last general election in 2009, the 2011 Indian anti-corruption movement by Anna Hazare, and other similar moves by Baba Ramdev, have gathered momentum and political interest. Issues such as Inflation, price rise and corruption were some of the chief issues.

There have been several instances of religious violence against Muslims since the partition of India in 1947, frequently in the form of violent attacks on Muslims by Hindu nationalist mobs that form a pattern of sporadic sectarian violence between the Hindu and Muslim communities. Over 10,000 people have been killed in Hindu-Muslim communal violence since 1950 in 6,933 instances of communal violence between 1954 and 1982.

Narendra Modi, the 14th Prime Minister of India, has elicited a number of public perceptions regarding his personality, background and policies.

Cow vigilante violence is a pattern of mob-based collective vigilante violence seen in India. The attacks are perpetuated by Hindu nationalists against non-Hindus to protect cows, which are considered sacred in Hinduism.

Conservatism in India refers to expressions of conservative politics in India. Conservative-oriented political parties have included the Bharatiya Janata Party, the Congress Nationalist Party, and the Uttar Pradesh Praja Party. In addition, a number of figures within the Indian National Congress, such as Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel were conservative.

Namaste Trump was a tour event held on 24 and 25 February 2020 in India. It was the inaugural visit of the then US President Donald Trump and his family to India. A rally event of the same name was held in Ahmedabad, Gujarat, and was the highlight of the tour, as a response to the "Howdy Modi" event held in Houston, Texas, in September 2019. The Motera Stadium hosted US President Trump and his family along with Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. An attendance of over 100,000 people was reported, with some speculating an attendance as high as 125,000. The tour was originally named "Kem Chho Trump" but was renamed by the Government of India to promote Indian nationalism over regionalism.

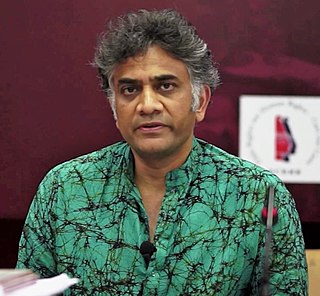

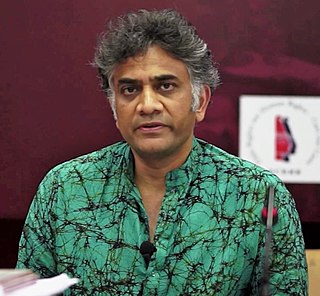

Aakar Patel is an Indian journalist, activist and author. He served as the head of Amnesty International in India between 2015 and 2019, and currently serves as the chair of the Board of Amnesty International in India. He is the author of Our Hindu Rashtra, an account of majoritarianism in India, and of Price of the Modi Years, which examines the administrative performance of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. In 2014, he authored a translation of Saadat Hasan Manto's Urdu non-fiction Why I Write.

The Bilkis Bano case relates to an attack that took place in the 2002 Gujarat riots, in which a gang of 11 men gang raped a pregnant woman named Bilkis Bano and killed numerous members of her family.