Related Research Articles

Christopher Columbus was an Italian explorer and navigator from the Republic of Genoa who completed four Spanish-based voyages across the Atlantic Ocean sponsored by the Catholic Monarchs, opening the way for the widespread European exploration and European colonization of the Americas. His expeditions were the first known European contact with the Caribbean and Central and South America.

Hispaniola is an island in the Caribbean that is part of the Greater Antilles. Hispaniola is the most populous island in the West Indies, and the region's second largest in area, after the island of Cuba. The 76,192-square-kilometre (29,418 sq mi) island is divided into two separate nations: the Spanish-speaking Dominican Republic (48,445 km2 to the east and the French/Haitian Creole-speaking Haiti (27,750 km2 to the west. The only other divided island in the Caribbean is Saint Martin, which is shared between France and the Netherlands.

During the Age of Discovery, a large scale colonization of the Americas, involving a number of European countries, took place primarily between the late 15th century and the early 19th century. The Norse had explored and colonized areas of Europe and the North Atlantic, colonizing Greenland and creating a short term settlement near the northern tip of Newfoundland circa 1000 AD. However, due to its long duration and importance, the later colonization by the European powers involving the continents of North America and South America is more well-known.

The Arawak are a group of Indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times from the Lokono of South America to the Taíno, who lived in the Greater Antilles and northern Lesser Antilles in the Caribbean. All these groups spoke related Arawakan languages.

The Columbian exchange, also known as the Columbian interchange, was the widespread transfer of plants, animals, precious metals, commodities, culture, human populations, technology, diseases, and ideas between the New World in the Western Hemisphere, and the Old World (Afro-Eurasia) in the Eastern Hemisphere, in the late 15th and following centuries. It is named after the Italian explorer Christopher Columbus and is related to the European colonization and global trade following his 1492 voyage. Some of the exchanges were purposeful. Some were accidental or unintended. Communicable diseases of Old World origin resulted in an 80 to 95 percent reduction in the number of Indigenous peoples of the Americas from the 15th century onwards, most severely in the Caribbean. The cultures of both hemispheres were significantly impacted by the migration of people, both free and enslaved, from the Old World to the New. European colonists and African slaves replaced Indigenous populations across the Americas, to varying degrees. The number of Africans taken to the New World was far greater than the number of Europeans moving to the New World in the first three centuries after Columbus.

Population figures for the Indigenous peoples of the Americas prior to European colonization have been difficult to establish. By the end of the 20th century, most scholars gravitated toward an estimate of around 50 million, with some historians arguing for an estimate of 100 million or more.

La Isabela in Puerto Plata Province, Dominican Republic was the first stable Spanish settlement and town in the Americas established in December 1493. The site is 42 km west of the city of Puerto Plata, adjacent to the village of El Castillo. The area now forms a National Historic Park.

At the time of first contact between Europe and the Americas, the Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean included the Taíno of the northern Lesser Antilles, most of the Greater Antilles and the Bahamas, the Kalinago of the Lesser Antilles, the Ciguayo and Macorix of parts of Hispaniola, and the Guanahatabey of western Cuba. The Kalinago have maintained an identity as an Indigenous people, with a reserved territory in Dominica.

Globalization, the flow of information, goods, capital, and people across political and geographic boundaries, allows infectious diseases to rapidly spread around the world, while also allowing the alleviation of factors such as hunger and poverty, which are key determinants of global health. The spread of diseases across wide geographic scales has increased through history. Early diseases that spread from Asia to Europe were bubonic plague, influenza of various types, and similar infectious diseases.

Ecological Imperialism: The Biological Expansion of Europe, 900-1900 is a 1986 book by environmental historian Alfred W. Crosby. The book builds on Crosby's earlier study, The Columbian Exchange, in which he described the complex global transfer of organisms that accompanied European colonial endeavors.

The Captaincy General of Santo Domingo was the first Capitancy in the New World, established by Spain in 1492 on the island of Hispaniola. The Capitancy, under the jurisdiction of the Real Audiencia of Santo Domingo, was granted administrative powers over the Spanish possessions in the Caribbean and most of its mainland coasts, making Santo Domingo the principal political entity of the early colonial period.

Seasoning, or the Seasoning, was the period of adjustment that slave traders and slaveholders subjected African slaves to following their arrival in the Americas. While modern scholarship has occasionally applied this term to the brief period of acclimatization undergone by European immigrants to the Americas, it most frequently and formally referred to the process undergone by enslaved people. Slave traders used the term "seasoning" to refer to the process of adjusting the enslaved Africans to the new climate, diet, geography, and ecology of the Americas. The term applied to both the physical acclimatization of the enslaved person to the environment, as well as that person's adjustment to a new social environment, labor regimen, and language. Slave traders and owners believed that if slaves survived this critical period of environmental seasoning, they were less likely to die and the psychological element would make them more easily controlled. This process took place immediately after the arrival of enslaved people during which their mortality rates were particularly high. These "new" or "saltwater" slaves were described as "outlandish" on arrival. Those who survived this process became "seasoned", and typically commanded a higher price in the market. For example, in eighteenth century Brazil, the price differential between "new" and "seasoned" slaves was about fifteen percent.

Although a variety of infectious diseases existed in the Americas in pre-Columbian times, the limited size of the populations, smaller number of domesticated animals with zoonotic diseases, and limited interactions between those populations hampered the transmission of communicable diseases. One notable infectious disease that may be of American origin is syphilis. Aside from that, most of the major infectious diseases known today originated in the Old World. The American era of limited infectious disease ended with the arrival of Europeans in the Americas and the Columbian exchange of microorganisms, including those that cause human diseases. Eurasian infections and epidemics had major effects on Native American life in the colonial period and nineteenth century, especially.

The chiefdoms of Hispaniola were the primary political units employed by the Taíno inhabitants of Hispaniola in the early historical era. At the time of European contact in 1492, the island was divided into five chiefdoms or cacicazgos, each headed by a cacique or paramount chief. Below him were lesser caciques presiding over villages or districts and nitaínos, an elite class in Taíno society.

In epidemiology, a virgin soil epidemic is an epidemic in which populations that previously were in isolation from a pathogen are immunologically unprepared upon contact with the novel pathogen. Virgin soil epidemics have occurred with European colonization, particularly when European explorers and colonists brought diseases to lands they conquered in the Americas, Australia and Pacific Islands.

The Taíno were a historic Indigenous peoples of the Caribbean, whose culture has been continued today by Taíno descendant communities and Taíno revivalist communities. At the time of European contact in the late 15th century, they were the principal inhabitants of most of what is now Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Jamaica, Haiti, Puerto Rico, the Bahamas, and the northern Lesser Antilles. The Lucayan branch of the Taíno were the first New World peoples encountered by Christopher Columbus, in the Bahama Archipelago on October 12, 1492. The Taíno spoke a dialect of the Arawakan language group. They lived in agricultural societies ruled by caciques with fixed settlements and a matrilineal system of kinship and inheritance. Taíno religion centered on the worship of zemis.

The Massachusetts smallpox epidemic or colonial epidemic was a smallpox outbreak that hit Massachusetts in 1633. Smallpox outbreaks were not confined to 1633 however, and occurred nearly every ten years. Smallpox was caused by two different types of variola viruses: variola major and variola minor. The disease was hypothesized to be transmitted due to an increase in the immigration of European settlers to the region who brought Old World smallpox aboard their ships.

Slavery in Cuba was a portion of the larger Atlantic Slave Trade that primarily supported Spanish plantation owners engaged in the sugarcane trade. It was practised on the island of Cuba from the 16th century until it was abolished by Spanish royal decree on October 7, 1886.

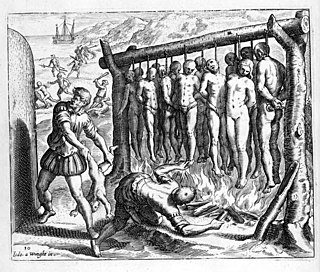

The Taíno genocide was committed against the Taíno indigenous people by the Spanish during their colonization of the Americas which they started in the Caribbean during the 16th century. It is estimated that before the Spanish Empire arrived on the island of Quisqueya, the Taíno community had between 100,000 and 1,000,000 inhabitants who were subjected to slavery and other treatment violent after the last Taíno chief was deposed in 1504. By 1514, the population had been reduced to just 32,000 Taíno, by 1565 the number was 200, and by 1802 they were declared extinct However, National Geographic carried out a report in 2019, revealing that descendants did exist and that their disappearance from records was part of a fictional story created by the Spanish Empire with the intention of erasing them of history.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McNeill, J. R.; Sampaolo, Marco; Wallenfeldt, Jeff (September 30, 2019) [28 September 2019]. "Columbian Exchange". Encyclopædia Britannica . Edinburgh: Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Archived from the original on April 21, 2020. Retrieved September 5, 2021.

- ↑ Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (2010). "The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas". Journal of Economic Perspectives . 24 (2): 163–188. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.232.9242 . doi:10.1257/jep.24.2.163. JSTOR 25703506.

- ↑ Mann, Charles C. (2011). 1493. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 286. ISBN 9780307265722.

- 1 2 3 4 Nunn, Nathan; Qian, Nancy (May 2010). "The Columbian Exchange: A History of Disease, Food, and Ideas". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 24 (2): 163–188. doi: 10.1257/jep.24.2.163 . ISSN 0895-3309.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Smallpox Devastates Indigenous Populations." Gale Encyclopedia of U.S. Economic History. Edited by Thomas Riggs. Gale, Farmington, MI, USA, 2015, https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/galegue/smallpox_devastates_indigenous_populations/0

- 1 2 3 4 Schroeder, Michael. "Epidemics in the Americas, 1450–1750." World History: A Comprehensive Reference Set. Edited by Facts on File,. Facts On File, New York, NY, USA, 2016, https://search.credoreference.com/content/entry/fofworld/epidemics_in_the_americas_1450_1750/0

- ↑ Cook, Noble David (1998). Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492-1650. Cambridge University Press. p. 26.

- ↑ Kipu (in Spanish). Ediciones ABYA-YALA. 1986. p. 85.

- ↑ Guerra, Francisco (Autumn 1988). "The Earliest American Epidemic: The Influenza of 1493". Social Science History. 12 (3): 303–325. doi:10.1017/S0145553200018599. JSTOR 1171451. PMID 11618144. S2CID 46540669.

- ↑ Martin, Manuela (September 26, 1985). "La gripe, peor que la espada". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582 . Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- ↑ Hardman, Lizabeth (January 18, 2011). Influenza Pandemics. Farmington Hills, MI: Greenhaven Publishing LLC. p. 37. ISBN 978-1-4205-0349-4.

- ↑ Byrne, Joseph Patrick (2008). Encyclopedia of Pestilence, Pandemics, and Plagues: A-M. ABC-CLIO. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-313-34102-1.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ Engerman, p. 486

- ↑ Keller, Claire; Burstein, Stanley M.; Loewen, James W. (February 1996). "Lies My Teacher Told Me: Everything Your American History Textbook Got Wrong". The History Teacher. 29 (2): 249. doi:10.2307/494748. ISSN 0018-2745. JSTOR 494748.

- ↑ The Sugar Revolutions and Slavery, U.S. Library of Congress

- 1 2 3 4 Esposito, Elena (2015). Side effects of immunities : the African slave trade (Report). Retrieved December 5, 2019.

- 1 2 Klein, Herbert S.; Engerman, Stanley L.; Haines, Robin; Shlomowitz, Ralph (January 2001). "Transoceanic Mortality: The Slave Trade in Comparative Perspective" (PDF). The William and Mary Quarterly. 58 (1): 93–117. doi:10.2307/2674420. JSTOR 2674420. PMID 18629973. S2CID 7096696. Archived from the original (PDF) on February 27, 2020.

- ↑ Rutman, Darrett B.; Rutman, Anita H. (January 1976). "Of Agues and Fevers: Malaria in the Early Chesapeake". The William and Mary Quarterly. 33 (1): 31–60. doi:10.2307/1921692. JSTOR 1921692. PMID 11633589.