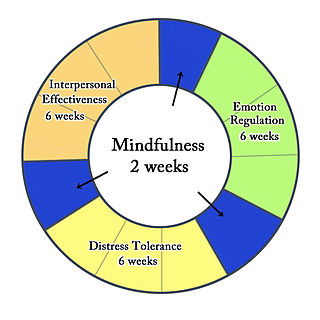

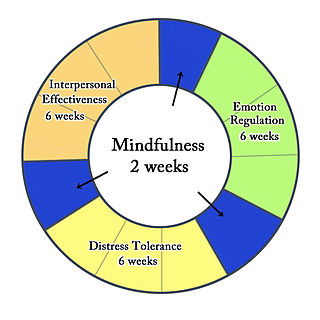

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that began with efforts to treat personality disorders and interpersonal conflicts. Evidence suggests that DBT can be useful in treating mood disorders and suicidal ideation, as well as for changing behavioral patterns such as self-harm and substance use. DBT evolved into a process in which the therapist and client work with acceptance and change-oriented strategies, and ultimately balance and synthesize them—comparable to the philosophical dialectical process of thesis and antithesis followed by synthesis.

Couples therapy attempts to improve romantic relationships and resolve interpersonal conflicts.

Discrete trial training (DTT) is a technique used by practitioners of applied behavior analysis (ABA) that was developed by Ivar Lovaas at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). DTT uses direct instruction and reinforcers to create clear contingencies that shape new skills. Often employed as an early intensive behavioral intervention (EIBI) for up to 30–40 hours per week for children with autism, the technique relies on the use of prompts, modeling, and positive reinforcement strategies to facilitate the child's learning. It previously used aversives to punish unwanted behaviors. DTT has also been referred to as the "Lovaas/UCLA model", "rapid motor imitation antecedent", "listener responding", errorless learning", and "mass trials".

Behaviour therapy or behavioural psychotherapy is a broad term referring to clinical psychotherapy that uses techniques derived from behaviourism and/or cognitive psychology. It looks at specific, learned behaviours and how the environment, or other people's mental states, influences those behaviours, and consists of techniques based on behaviorism’s theory of learning: respondent or operant conditioning. Behaviourists who practice these techniques are either behaviour analysts or cognitive-behavioural therapists. They tend to look for treatment outcomes that are objectively measurable. Behaviour therapy does not involve one specific method, but it has a wide range of techniques that can be used to treat a person's psychological problems.

Contingency management (CM) is the application of the three-term contingency, which uses stimulus control and consequences to change behavior. CM originally derived from the science of applied behavior analysis (ABA), but it is sometimes implemented from a cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) framework as well.

Psychological resistance, also known as psychological resistance to change, is the phenomenon often encountered in clinical practice in which patients either directly or indirectly exhibit paradoxical opposing behaviors in presumably a clinically initiated push and pull of a change process. In other words, the concept of psychological resistance is that patients are likely to resist physician suggestions to change behavior or accept certain treatments regardless of whether that change will improve their condition. It impedes the development of authentic, reciprocally nurturing experiences in a clinical setting. It is established that the common source of resistances and defenses is shame. This and similar negative attitudes may be the result of social stigmatization of a particular condition, such as psychological insulin resistance towards treatment of diabetes.

Emotionally focused therapy and emotion-focused therapy (EFT) are a family of related approaches to psychotherapy with individuals, couples, or families. EFT approaches include elements of experiential therapy, systemic therapy, and attachment theory. EFT is usually a short-term treatment. EFT approaches are based on the premise that human emotions are connected to human needs, and therefore emotions have an innately adaptive potential that, if activated and worked through, can help people change problematic emotional states and interpersonal relationships. Emotion-focused therapy for individuals was originally known as process-experiential therapy, and it is still sometimes called by that name.

Functional analytic psychotherapy (FAP) is a psychotherapeutic approach based on clinical behavior analysis (CBA) that focuses on the therapeutic relationship as a means to maximize client change. Specifically, FAP suggests that in-session contingent responding to client target behaviors leads to significant therapeutic improvements.

Parent management training (PMT), also known as behavioral parent training (BPT) or simply parent training, is a family of treatment programs that aims to change parenting behaviors, teaching parents positive reinforcement methods for improving pre-school and school-age children's behavior problems.

Behavioral activation (BA) is a third generation behavior therapy for treating depression. It is one functional analytic psychotherapy which are based on a Skinnerian psychological model of behavior change, generally referred to as applied behavior analysis. This area is also a part of what is called clinical behavior analysis (CBA) and makes up one of the most effective practices in the professional practice of behavior analysis. The technique can also be used from a cognitive-behavior therapy framework.

A clinical formulation, also known as case formulation and problem formulation, is a theoretically-based explanation or conceptualisation of the information obtained from a clinical assessment. It offers a hypothesis about the cause and nature of the presenting problems and is considered an adjunct or alternative approach to the more categorical approach of psychiatric diagnosis. In clinical practice, formulations are used to communicate a hypothesis and provide framework for developing the most suitable treatment approach. It is most commonly used by clinical psychologists and is deemed to be a core component of that profession. Mental health nurses, social workers, and some psychiatrists may also use formulations.

Common factors theory, a theory guiding some research in clinical psychology and counseling psychology, proposes that different approaches and evidence-based practices in psychotherapy and counseling share common factors that account for much of the effectiveness of a psychological treatment. This is in contrast to the view that the effectiveness of psychotherapy and counseling is best explained by specific or unique factors that are suited to treatment of particular problems. According to one review, "it is widely recognized that the debate between common and unique factors in psychotherapy represents a false dichotomy, and these factors must be integrated to maximize effectiveness". In other words, "therapists must engage in specific forms of therapy for common factors to have a medium through which to operate". Common factors is one route by which psychotherapy researchers have attempted to integrate psychotherapies.

Donald H. Baucom, is a clinical psychology faculty member at the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill. He is recognized for founding the field of Cognitive-Behavioral Couples Therapy. Baucom is also recognized as one of the top marital therapists and most prolific researchers in this field. Currently, Baucom's National Cancer Institute funded study, CanThrive, has the largest observationally coded sample of any couples study to date.

Jack A. Apsche was an American psychologist who has focused his work on adolescents with behavior problems. Apsche was also an author, artist, presenter, consultant and lecturer.

The mainstay of management of borderline personality disorder is various forms of psychotherapy with medications being found to be of little use.

Clinical Behavior Analysis is one of several ABA subspecialty fact sheets produced by the BACB in partnership with subject matter experts (SMEs).

Family therapy is a branch of psychology and clinical social work that works with families and couples in intimate relationships to nurture change and development. It tends to view change in terms of the systems of interaction between family members.

Mode deactivation therapy (MDT) is a psychotherapeutic approach that addresses dysfunctional emotions, maladaptive behaviors and cognitive processes and contents through a number of goal-oriented, explicit systematic procedures. The name refers to the process of mode deactivation that is based on the concept of cognitive modes as introduced by Aaron T. Beck. The MDT methodology was developed by Jack A. Apsche by combining the unique validation–clarification–redirection (VCR) process step with elements from acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), dialectical behavior therapy (DBT), and mindfulness to bring about durable behavior change.

Jay Lebow is an American family psychologist who is senior scholar at the Family Institute at Northwestern University, clinical professor at Northwestern University and is editor-in-chief of the journal Family Process. He is board certified by the American Board of Professional Psychology. Lebow is known for his publications and presentations about the practice of couple and family therapy, integrative psychotherapy, the relationship of research and psychotherapy practice, and psychotherapy in difficult divorce, as well as for his role as an editor in the fields of couple and family therapy and family science. He is the author or editor of 13 books and has written 200 journal articles and book chapters.

Co-therapy or conjoint therapy is a kind of psychotherapy conducted with more than one therapist present. This kind of therapy is especially applied during couple therapy. Carl Whitaker and Virginia Satir are credited as the founders of co-therapy. Co-therapy dates back to the early twentieth century in Vienna, where psychoanalytic practices were first taking place. It was originally named "multiple therapy" by Alfred Alder, and later introduced separately as "co-therapy" in the 1940s. Co-therapy began with two therapists of differing abilities, one essentially learning from the other, and providing the opportunity to hear feedback on their work.