Cybercrime is a crime involving a computer or computer network. The computer may have been used in committing the crime, or it may be the target. Cybercrime may harm someone's security or finances.

Cyberterrorism is the use of the Internet to conduct violent acts that result in, or threaten, the loss of life or significant bodily harm, in order to achieve political or ideological gains through threat or intimidation. Acts of deliberate, large-scale disruption of computer networks, especially of personal computers attached to the Internet by means of tools such as computer viruses, computer worms, phishing, malicious software, hardware methods, programming scripts can all be forms of internet terrorism. Cyberterrorism is a controversial term. Some authors opt for a very narrow definition, relating to deployment by known terrorist organizations of disruption attacks against information systems for the primary purpose of creating alarm, panic, or physical disruption. Other authors prefer a broader definition, which includes cybercrime. Participating in a cyberattack affects the terror threat perception, even if it isn't done with a violent approach. By some definitions, it might be difficult to distinguish which instances of online activities are cyberterrorism or cybercrime.

The National Police Agency is a law enforcement agency under the National Public Safety Commission of the Cabinet Office. It is the central agency of the Japanese police system, and the central coordinating agency of law enforcement in situations of national emergency in Japan.

The Australian High Tech Crime Centre (AHTCC) are hosted by the Australian Federal Police (AFP) at their headquarters in Canberra. Under the auspices of the AFP, the AHTCC is party to the formal Joint Operating Arrangement established between the AFP, the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation and the Computer Network Vulnerability Team of the Australian Signals Directorate.

The United States Computer Emergency Readiness Team (US-CERT) is an organization within the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA). Specifically, US-CERT is a branch of the Office of Cybersecurity and Communications' (CS&C) National Cybersecurity and Communications Integration Center (NCCIC).

A computer emergency response team (CERT) is an expert group that handles computer security incidents. Alternative names for such groups include computer emergency readiness team and computer security incident response team (CSIRT). A more modern representation of the CSIRT acronym is Cyber Security Incident Response Team.

The National Police Agency, Ministry of the Interior is an agency under the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of China (Taiwan) which oversees all police forces on a national level. The National Police Agency is headquartered in Taipei City.

The Australian Intelligence Community (AIC) and the National Intelligence Community (NIC) or National Security Community of the Australian Government are the collectives of statutory intelligence agencies, policy departments, and other government agencies concerned with protecting and advancing the national security and national interests of the Commonwealth of Australia. The intelligence and security agencies of the Australian Government have evolved since the Second World War and the Cold War and saw transformation and expansion during the Global War on Terrorism with military deployments in Afghanistan, Iraq and against ISIS in Syria. Key international and national security issues for the Australian Intelligence Community include terrorism and violent extremism, cybersecurity, transnational crime, the rise of China, and Pacific regional security.

Jingjing and Chacha are the cartoon mascots of the Internet Surveillance Division of the Public Security Bureau in Shenzhen, People's Republic of China. Debuting on January 22, 2006, they are used to, amongst other things, inform Chinese Internet users what is and is not legal to consult or write on the Chinese Internet. According to the director of the Shenzhen Internet police, "[we published] the image of Internet Police in the form of a cartoon [...] to let all internet users know that the Internet is not a place beyond of law [and that] the Internet Police will maintain order in all online behavior."

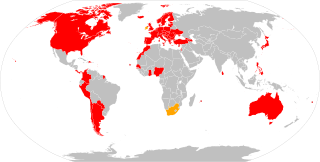

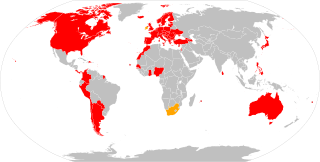

The Convention on Cybercrime, also known as the Budapest Convention on Cybercrime or the Budapest Convention, is the first international treaty seeking to address Internet and computer crime (cybercrime) by harmonizing national laws, improving investigative techniques, and increasing cooperation among nations. It was drawn up by the Council of Europe in Strasbourg, France, with the active participation of the Council of Europe's observer states Canada, Japan, the Philippines, South Africa and the United States.

Cyber police are police departments or government agencies in charge of stopping cybercrime. Examples include:

Beginning on 27 April 2007, a series of cyberattacks targeted websites of Estonian organizations, including Estonian parliament, banks, ministries, newspapers and broadcasters, amid the country's disagreement with Russia about the relocation of the Bronze Soldier of Tallinn, an elaborate Soviet-era grave marker, as well as war graves in Tallinn. Most of the attacks that had any influence on the general public were distributed denial of service type attacks ranging from single individuals using various methods like ping floods to expensive rentals of botnets usually used for spam distribution. Spamming of bigger news portals commentaries and defacements including that of the Estonian Reform Party website also occurred. Research has also shown that large conflicts took place to edit the English-language version of the Bronze Soldier's Wikipedia page.

Cyber crime, or computer crime, refers to any crime that involves a computer and a network. The computer may have been used in the commission of a crime, or it may be the target. Netcrime refers, more precisely, to criminal exploitation of the Internet. Issues surrounding this type of crime have become high-profile, particularly those surrounding hacking, copyright infringement, identity theft, child pornography, and child grooming. There are also problems of privacy when confidential information is lost or intercepted, lawfully or otherwise.

There is no commonly agreed single definition of “cybercrime”. It refers to illegal internet-mediated activities that often take place in global electronic networks. Cybercrime is "international" or "transnational" – there are ‘no cyber-borders between countries'. International cybercrimes often challenge the effectiveness of domestic and international law, and law enforcement. Because existing laws in many countries are not tailored to deal with cybercrime, criminals increasingly conduct crimes on the Internet in order to take advantages of the less severe punishments or difficulties of being traced. No matter, in developing or developed countries, governments and industries have gradually realized the colossal threats of cybercrime on economic and political security and public interests. However, complexity in types and forms of cybercrime increases the difficulty to fight back. In this sense, fighting cybercrime calls for international cooperation. Various organizations and governments have already made joint efforts in establishing global standards of legislation and law enforcement both on a regional and on an international scale. China–United States cooperation is one of the most striking progress recently, because they are the top two source countries of cybercrime.

The Cyber Division (CyD) is a Federal Bureau of Investigation division which heads the national effort to investigate and prosecute internet crimes, including "cyber based terrorism, espionage, computer intrusions, and major cyber fraud." This division of the FBI uses the information it gathers during investigation to inform the public of current trends in cyber crime. It focuses around three main priorities: computer intrusion, identity theft, and cyber fraud. It was created in 2002.

The Indian Computer Emergency Response Team is an office within the Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology of the Government of India. It is the nodal agency to deal with cyber security threats like hacking and phishing. It strengthens security-related defence of the Indian Internet domain.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to computer security:

The Security Bureau of the National Police Agency is a bureau of the Japan's National Police Agency in charge of national-level internal security affairs. It supervises the Security Bureau and the Public Security Bureau of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department, and Security departments of other Prefectural police headquarters for those issues.

The National Cyber Security Centre (NCSC) is a government computer security organisation in Ireland, an operational arm of the Department of the Environment, Climate and Communications. The NCSC was developed in 2013 and formally established by the Irish government in July 2015. It is responsible for Ireland's cyber security, with a primary focus on securing government networks, protecting critical national infrastructure, and assisting businesses and citizens in protecting their own systems. The NCSC incorporates the Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT-IE).

Azerbaijan Computer Emergency Response Team, officially known as Azerbaijan Government CERT, is a computer emergency response team of the Republic of Azerbaijan responsible for cybersecurity and gathering data concerning information technology. It operates under the Special Communication and Information Security State Service of the government of Azerbaijan. It collectes data within its framework from relevant sources, including internet users, computer engineering groups, individuals or organizations and software developers. It coordinates with the foreign countries for gathering and analysing data from cybersecurity incidents involving both software and hardware tools designed for the prevention of internet and computer security.