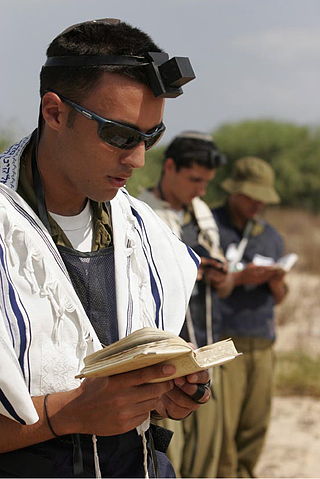

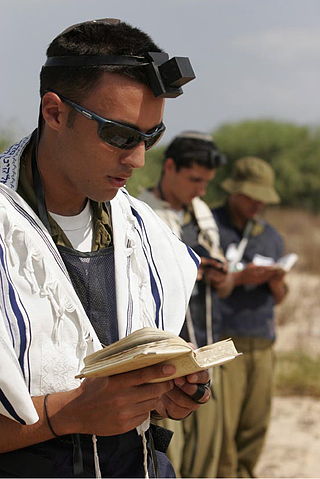

Jewish prayer is the prayer recitation that forms part of the observance of Rabbinic Judaism. These prayers, often with instructions and commentary, are found in the Siddur, the traditional Jewish prayer book.

Shiva is the week-long mourning period in Judaism for first-degree relatives. The ritual is referred to as "sitting shiva" in English. The shiva period lasts for seven days following the burial. Following the initial period of despair and lamentation immediately after the death, shiva embraces a time when individuals discuss their loss and accept the comfort of others.

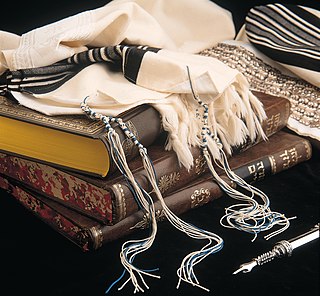

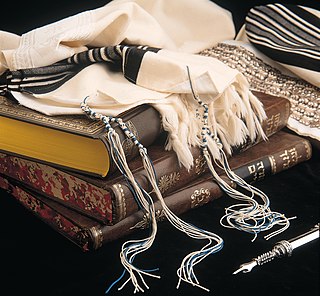

A tallit (טלית) is a fringed garment worn as a prayer shawl by religious Jews. The tallit has special twined and knotted fringes known as tzitzit attached to its four corners. The cloth part is known as the beged ("garment") and is usually made from wool or cotton, although silk is sometimes used for a tallit gadol.

Tefillin, or phylacteries, are a set of small black leather boxes with leather straps containing scrolls of parchment inscribed with verses from the Torah. Tefillin are worn by adult Jews during weekday and Sunday morning prayers. In Orthodox and traditional communities, they are worn solely by men, while some Reform and Conservative (Masorti) communities allow them to be worn by any gender. In Jewish law (halacha), women are exempt from most time-dependent positive commandments, which include tefillin.

Tzniut describes the character trait of modesty and discretion, as well as a group of Jewish laws pertaining to conduct. The concept is most important within Orthodox Judaism.

A niddah, in traditional Judaism, is a woman who has experienced a uterine discharge of blood, or a woman who has menstruated and not yet completed the associated requirement of immersion in a mikveh.

Jacob ben Meir, best known as Rabbeinu Tam, was one of the most renowned Ashkenazi Jewish rabbis and leading French Tosafists, a leading halakhic authority in his generation, and a grandson of Rashi. Known as "Rabbeinu", he acquired the Hebrew suffix "Tam" meaning straightforward; it was originally used in the Book of Genesis to describe his biblical namesake, Jacob.

Tzitzit are specially knotted ritual fringes, or tassels, worn in antiquity by Israelites and today by observant Jews and Samaritans. Tzitzit are usually attached to the four corners of the tallit gadol, usually referred to simply as a tallit or tallis; and tallit katan. Through synecdoche, a tallit katan may be referred to as tzitzit.

Tekhelet is a highly valued dye described as either "sky blue", or "light blue", that held great significance in ancient Mediterranean civilizations. In the Hebrew Bible and Jewish tradition, tekhelet was used to color the clothing of the High Priest, the tapestries in the Tabernacle, and the tzitzit (fringes) attached to the corners of four-cornered garments, including the tallit. The mention of tekhelet is particularly notable in the third paragraph of the Shema, referencing Numbers 15:37–41.

Kosher foods are foods that conform to the Jewish dietary regulations of kashrut. The laws of kashrut apply to food derived from living creatures and kosher foods are restricted to certain types of mammals, birds and fish meeting specific criteria; the flesh of any animals that do not meet these criteria is forbidden by the dietary laws. Furthermore, kosher mammals and birds must be slaughtered according to a process known as shechita and their blood may never be consumed and must be removed from the meat by a process of salting and soaking in water for the meat to be permissible for use. All plant-based products, including fruits, vegetables, grains, herbs and spices, are intrinsically kosher, although certain produce grown in the Land of Israel is subjected to other requirements, such as tithing, before it may be consumed.

A shtreimel is a fur hat worn by some Ashkenazi Jewish men, mainly members of Hasidic Judaism, on Shabbat and Jewish holidays and other festive occasions. In Jerusalem, the shtreimel is also worn by Litvak Jews. The shtreimel is generally worn after marriage, although it may be worn by boys after bar-mitzvah age in some communities.

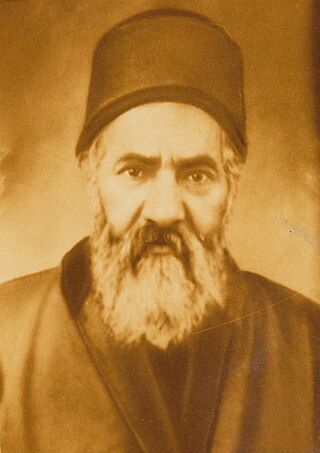

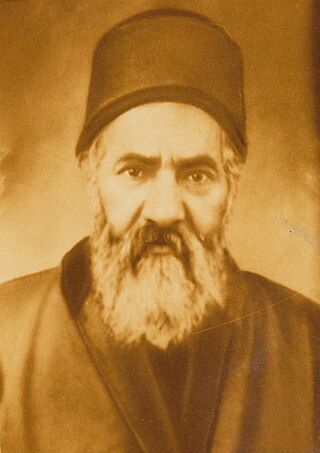

Yaakov Chaim Sofer was a Sephardic rabbi, kabbalist, talmudist and poseq. He is the author of Kaf Hakhaim, a work of halakha.

Shatnez is cloth containing both wool and linen (linsey-woolsey), which Jewish law, derived from the Torah, prohibits wearing. The relevant biblical verses prohibit wearing wool and linen fabrics in one garment, the blending of different species of animals, and the planting together of different kinds of seeds.

A seudat mitzvah, in Judaism, is an obligatory festive meal, usually referring to the celebratory meal following the fulfillment of a mitzvah (commandment), such as a bar mitzvah, bat mitzvah, a wedding, a brit milah, or a siyum. Seudot fixed in the calendar are also considered seudot mitzvah, but many have their own, more commonly used names.

Shlach, Shelach, Sh'lah, Shlach Lecha, or Sh'lah L'kha is the 37th weekly Torah portion in the annual Jewish cycle of Torah reading and the fourth in the Book of Numbers. Its name comes from the first distinctive words in the parashah, in Numbers 13:2. Shelach is the sixth and lecha is the seventh word in the parashah. The parashah tells the story of the twelve spies sent to assess the promised land, commandments about offerings, the story of the Sabbath violator, and the commandment of the fringes.

The tithe is specifically mentioned in the Books of Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The tithe system was organized in a seven-year cycle, the seventh-year corresponding to the Shemittah-cycle in which year tithes were broken-off, and in every third and sixth-year of this cycle the second tithe replaced with the poor man's tithe. These tithes were akin to taxes for the people of Israel and were mandatory, not optional giving. This tithe was distributed locally "within thy gates" to support the Levites and assist the poor. Every year, Bikkurim, terumah, ma'aser rishon and terumat ma'aser were separated from the grain, wine and oil. Initially, the commandment to separate tithes from one's produce only applied when the entire nation of Israel had settled in the Land of Israel. The Returnees from the Babylonian exile who had resettled the country were a Jewish minority, and who, although they were not obligated to tithe their produce, put themselves under a voluntary bind to do so, and which practice became obligatory upon all.

Jewish heresy refers to those beliefs which contradict the traditional doctrines of Rabbinic Judaism, including theological beliefs and opinions about the practice of halakha. Jewish tradition contains a range of statements about heretics, including laws for how to deal with them in a communal context, and statements about the divine punishment they are expected to receive.

Religious clothing is clothing which is worn in accordance with religious practice, tradition or significance to a faith group. It includes clerical clothing such as cassocks, and religious habit, robes, and other vestments. Accessories include hats, wedding rings, crucifixes, etc.

Kil'ayim are the prohibitions in Jewish law which proscribe the planting of certain mixtures of seeds, grafting, the mixing of plants in vineyards, the crossbreeding of animals, the formation of a team in which different kinds of animals work together, and the mixing of wool with linen in garments.

The clothing of the people in biblical times was made from wool, linen, animal skins, and perhaps silk. Most events in the Hebrew Bible and New Testament take place in ancient Israel, and thus most biblical clothing is ancient Hebrew clothing. They wore underwear and cloth skirts.