A turban is a type of headwear based on cloth winding. Featuring many variations, it is worn as customary headwear by people of various cultures. Communities with prominent turban-wearing traditions can be found in the Indian subcontinent, Southeast Asia, the Arabian Peninsula, the Middle East, the Balkans, the Caucasus, Central Asia, North Africa, West Africa, East Africa, and amongst some Turkic peoples in Russia as well as Ashkenazi Jews.

A folk costume expresses an identity through costume, which is usually associated with a geographic area or a period of time in history. It can also indicate social, marital or religious status. If the costume is used to represent the culture or identity of a specific ethnic group, it is usually known as ethnic costume. Such costumes often come in two forms: one for everyday occasions, the other for traditional festivals and formal wear.

A lavalava, also known as an 'ie, short for 'ie lavalava, is an article of daily clothing traditionally worn by Polynesians and other Oceanic peoples. It consists of a single rectangular cloth worn similarly to a wraparound skirt or kilt. The term lavalava is both singular and plural in the Samoan language.

The traditional culture of Samoa is a communal way of life based on Fa'a Samoa, the unique socio-political culture. In Samoan culture, most activities are done together. The traditional living quarters, or fale (houses), contain no walls and up to 20 people may sleep on the ground in the same fale. During the day, the fale is used for chatting and relaxing. One's family is viewed as an integral part of a person's life. The aiga or extended family lives and works together. Elders in the family are greatly respected and hold the highest status, and this may be seen at a traditional Sunday umu.

A headscarf is a scarf covering most or all of the top of a person's, usually women's, hair and head, leaving the face uncovered. A headscarf is formed of a triangular cloth or a square cloth folded into a triangle, with which the head is covered.

The Tongan archipelago has been inhabited for perhaps 3000 years, since settlement in late Lapita times. The culture of its inhabitants has surely changed greatly over this long time period. Before the arrival of European explorers in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the Tongans were in frequent contact with their nearest Oceanic neighbors, Fiji and Samoa. In the 19th century, with the arrival of Western traders and missionaries, Tongan culture changed dramatically. Some old beliefs and habits were thrown away and others adopted. Some accommodations made in the 19th century and early 20th century are now being challenged by changing Western civilization. Hence Tongan culture is far from a unified or monolithic affair, and Tongans themselves may differ strongly as to what it is "Tongan" to do, or not do. Contemporary Tongans often have strong ties to overseas lands. They may have been migrant workers in New Zealand, or have lived and traveled in New Zealand, Australia, or the United States. Many Tongans now live overseas, in a Tongan diaspora, and send home remittances to family members who prefer to remain in Tonga. Tongans themselves often have to operate in two different contexts, which they often call anga fakatonga, the traditional Tongan way, and anga fakapālangi, the Western way. A culturally adept Tongan learns both sets of rules and when to switch between them.

The culture of Fiji is a tapestry of native Fijian, Indian, European, Chinese, and other nationalities. Culture polity traditions, language, food costume, belief system, architecture, arts, craft, music, dance, and sports will be discussed in this article to give you an indication of Fiji's indigenous community but also the various communities which make up Fiji as a modern culture and living. The indigenous culture is an active and living part of everyday life for the majority of the population.

Tapa cloth is a barkcloth made in the islands of the Pacific Ocean, primarily in Tonga, Samoa and Fiji, but as far afield as Niue, Cook Islands, Futuna, Solomon Islands, Java, New Zealand, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and Hawaii. In French Polynesia it has nearly disappeared, except for some villages in the Marquesas.

Vatulele is a coral and volcanic island 32 kilometres south of Viti Levu, Fiji's largest island. Situated at 18.50° South and 177.63° East, Vatulele has an area of 32 square kilometres. Its maximum altitude is only 320 metres.

Pāreu or pareo is the Cook Islands and Tahitian word for a wraparound skirt. Originally it was used only to refer to women's skirts, as men wore a loincloth, called a maro. Nowadays the term is applied to any piece of cloth worn wrapped around the body, worn by males or females. It is related to the Malay sarong, Filipino malong, tapis and patadyong, Samoan lavalava, Tongan tupenu and other such garments of the Pacific Islands such as the Hawaiian Islands, Marquesas Islands, New Zealand, Fiji and Tremiti island

A dastār which derives from dast-e-yār or "the hand of God", is an item of headwear associated with Sikhism, and is an important part of Sikh culture. The word is loaned from Persian through Punjabi. In Persian, the word dastār can refer to any kind of turban and replaced the original word for turban, dolband (دلبند), from which the English word is derived.

Barkcloth or bark cloth is a versatile material that was once common in Asia, Africa, and the Pacific. Barkcloth comes primarily from trees of the family Moraceae, including Broussonetia papyrifera, Artocarpus altilis, Artocarpus tamaran, and Ficus natalensis. It is made by beating sodden strips of the fibrous inner bark of these trees into sheets, which are then finished into a variety of items. Many texts that mention "paper" clothing are actually referring to barkcloth.

Outside Western cultures, men's clothing commonly includes skirts and skirt-like garments; however, in North America and much of Europe, the wearing of a skirt is today usually seen as typical for women and girls and not men and boys, the most notable exceptions being the cassock and the kilt. People have variously attempted to promote the wearing of skirts by men in Western culture and to do away with this gender distinction.

A grass skirt is a costume and garment made with layers of plant fibres such as grasses (Poaceae) and leaves that is fastened at the waistline.

Pagri, sometimes also transliterated as pagari, is the term for turban used in the Indian subcontinent. It specifically refers to a headdress that is worn by men and women, which needs to be manually tied. Other names include sapho.

Headgear, headwear, or headdress is the name given to any element of clothing which is worn on one's head, including hats, helmets, turbans and many other types. Headgear is worn for many purposes, including protection against the elements, decoration, or for religious or cultural reasons, including social conventions.

The Dumalla is a type of turban worn by Sikhs. This turban is worn mainly by Sikhs who are initiated into the Khalsa, through participating in the Amrit Sanchar but can be worn by all Sikhs. The word Dumalla means "Du" meaning two and "Malla" meaning cloth or fabric. This is because there will usually be one fabric to form the base of the turban and a second to wrap around the base to form the turban itself. There many different types of Dumalla, in many different sizes and colours.

A sulu is a kilt-like garment worn by men and women in Fiji since colonisation in the nineteenth century.

History of clothing in the Indian subcontinent can be traced to the Indus Valley Civilization or earlier. Indians have mainly worn clothing made up of locally grown cotton. India was one of the first places where cotton was cultivated and used even as early as 2500 BCE during the Harappan era. The remnants of the ancient Indian clothing can be found in the figurines discovered from the sites near the Indus Valley Civilisation, the rock-cut sculptures, the cave paintings, and human art forms found in temples and monuments. These scriptures view the figures of human wearing clothes which can be wrapped around the body. Taking the instances of the sari to that of turban and the dhoti, the traditional Indian wears were mostly tied around the body in various ways.

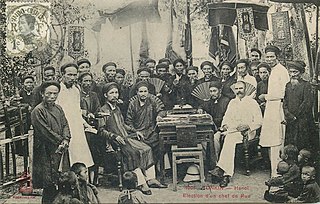

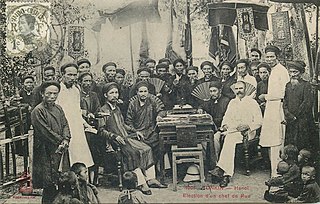

Khăn vấn, khăn đóng or khăn xếp, is a kind of turban worn by Vietnamese people which had been popular since ancient times. The word vấn means coil around. The word khăn means cloth, towel or scarf.