Northampton County is a county located in the Commonwealth of Virginia. As of the 2020 census, the population was 12,282. Its county seat is Eastville. Northampton and Accomack Counties are a part of the larger Eastern Shore of Virginia.

Slavery in the colonial history of the United States refers to the institution of slavery as it existed in the European colonies which eventually became part of the United States. Slavery developed due to a combination of factors, primarily the labour demands for establishing and maintaining European colonies, which had resulted in the Atlantic slave trade. Slavery existed in every European colony in the Americas during the early modern period, and both Africans and indigenous peoples were victims of enslavement by European colonizers during the era.

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered voluntarily for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, or imposed involuntarily as a judicial punishment. Many came with forged or no contract they ever saw.

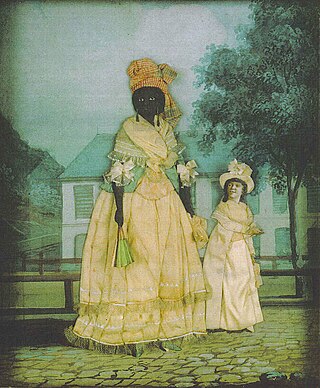

In the British colonies in North America and in the United States before the abolition of slavery in 1865, free Negro or free Black described the legal status of African Americans who were not enslaved. The term was applied both to formerly enslaved people (freedmen) and to those who had been born free, whether of African or mixed descent.

In societies that regard some races or ethnic groups of people as dominant or superior and others as subordinate or inferior, hypodescent refers to the automatic assignment of children of a mixed union to the subordinate group. The opposite practice is hyperdescent, in which children are assigned to the race that is considered dominant or superior.

Partus sequitur ventrem was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born there; the doctrine mandated that children of slave mothers would inherit the legal status of their mothers. As such, children of enslaved women would be born into slavery. The legal doctrine of partus sequitur ventrem was derived from Roman civil law, specifically the portions concerning slavery and personal property (chattels), as well as the common law of personal property; analogous legislation existed in other civilizations including Medieval Egypt in Africa and Korea in Asia.

The Virginia Slave Codes of 1705, were a series of laws enacted by the Colony of Virginia's House of Burgesses in 1705 regulating the interactions between slaves and citizens of the crown colony of Virginia. The enactment of the Slave Codes is considered to be the consolidation of slavery in Virginia, and served as the foundation of Virginia's slave legislation. All servants from non-Christian lands became slaves. There were forty one parts of this code each defining a different part and law surrounding the slavery in Virginia. These codes overruled the other codes in the past and any other subject covered by this act are canceled.

Anthony Johnson was an Angolan-born man who achieved wealth in the early 17th-century Colony of Virginia. Held as an indentured servant in 1621, he earned his freedom after several years and was granted land by the colony.

Slavery was practiced in Massachusetts bay by Native Americans before European settlement, and continued until its abolition in the 1700s. Although slavery in the United States is typically associated with the Caribbean and the Antebellum American South, enslaved people existed to a lesser extent in New England: historians estimate that between 1755 and 1764, the Massachusetts enslaved population was approximately 2.2 percent of the total population; the slave population was generally concentrated in the industrial and coastal towns. Unlike in the American South, enslaved people in Massachusetts had legal rights, including the ability to file legal suits in court.

When the Dutch and Swedes established colonies in the Delaware Valley of what is now Pennsylvania, in North America, they quickly imported enslaved Africans for labor; the Dutch also transported them south from their colony of New Netherland. Enslavement was documented in this area as early as 1639. William Penn and the colonists who settled in Pennsylvania tolerated slavery. Still, the English Quakers and later German immigrants were among the first to speak out against it. Many colonial Methodists and Baptists also opposed it on religious grounds. During the Great Awakening of the late 18th century, their preachers urged slaveholders to free their slaves. High British tariffs in the 18th century discouraged the importation of additional slaves, and encouraged the use of white indentured servants and free labor.

Elizabeth Key Grinstead (or Greenstead) (1630 – January 20, 1665) was one of the first Black people in the Thirteen Colonies to sue for freedom from slavery and win. Key won her freedom and that of her infant son, John Grinstead, on July 21, 1656, in the Colony of Virginia.

Slavery in Maryland lasted over 200 years, from its beginnings in 1642 when the first Africans were brought as slaves to St. Mary's City, to its end after the Civil War. While Maryland developed similarly to neighboring Virginia, slavery declined in Maryland as an institution earlier, and it had the largest free black population by 1860 of any state. The early settlements and population centers of the province tended to cluster around the rivers and other waterways that empty into the Chesapeake Bay. Maryland planters cultivated tobacco as the chief commodity crop, as the market for cash crops was strong in Europe. Tobacco was labor-intensive in both cultivation and processing, and planters struggled to manage workers as tobacco prices declined in the late 17th century, even as farms became larger and more efficient. At first, indentured servants from England supplied much of the necessary labor but, as England's economy improved, fewer came to the colonies. Maryland colonists turned to importing indentured and enslaved Africans to satisfy the labor demand.

Slavery in Virginia began with the capture and enslavement of Native Americans during the early days of the English Colony of Virginia and through the late eighteenth century. They primarily worked in tobacco fields. Africans were first brought to colonial Virginia in 1619, when 20 Africans from present-day Angola arrived in Virginia aboard the ship The White Lion.

Freedom suits were lawsuits in the Thirteen Colonies and the United States filed by slaves against slaveholders to assert claims to freedom, often based on descent from a free maternal ancestor, or time held as a resident in a free state or territory.

John Punch was an enslaved African who lived in the colony of Virginia. Thought to have been an indentured servant, Punch attempted to escape to Maryland and was sentenced in July 1640 by the Virginia Governor's Council to serve as a slave for the remainder of his life. Two European men who ran away with him received a lighter sentence of extended indentured servitude. For this reason, some historians consider John Punch the "first official slave in the English colonies," and his case as the "first legal sanctioning of lifelong slavery in the Chesapeake." Some historians also consider this to be one of the first legal distinctions between Europeans and Africans made in the colony, and a key milestone in the development of the institution of slavery in the United States.

Slavery was legally practiced in the Province of North Carolina and the state of North Carolina until January 1, 1863, when President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation. Prior to statehood, there were 41,000 enslaved African-Americans in the Province of North Carolina in 1767. By 1860, the number of slaves in the state of North Carolina was 331,059, about one third of the total population of the state. In 1860, there were nineteen counties in North Carolina where the number of slaves was larger than the free white population. During the antebellum period the state of North Carolina passed several laws to protect the rights of slave owners while disenfranchising the rights of slaves. There was a constant fear amongst white slave owners in North Carolina of slave revolts from the time of the American Revolution. Despite their circumstances, some North Carolina slaves and freed slaves distinguished themselves as artisans, soldiers during the Revolution, religious leaders, and writers.

John Graweere also known as John Gowen was one of the First Africans in Virginia, who was a servant who earned enough money to pay for his son's freedom. He filed a lawsuit to free his son, arguing that he wanted to raise him as a Christian. The court agreed and freed the son.

Jane Webb, also known as Jane Williams was an indentured servant in Northampton County of the Colony of Virginia. She entered a seven-year contract with Thomas Savage so that she could marry an enslaved man named Left. It allowed for children born during those seven years to be bound over to Savage, but after she was free, Webb expected her children to be free. Savage used the courts to his advantage and also used stall tactics to prevent the case from being settled. In the end, Left and their children were enslaved to Savage and his heirs.

Polly Strong was an enslaved woman in the Northwest Territory, in present-day Indiana. She was born after the Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery. Slavery was prohibited by the Constitution of Indiana in 1816. Two years later, Strong's mother Jenny and attorney Moses Tabbs asked for a writ of habeas corpus for Polly and her brother James in 1818. Judge Thomas H. Blake produced indentures, Polly for 12 more years and James for four more years of servitude. The case was dismissed in 1819.

Mary Bateman Clark (1795–1840) was an American woman, born into slavery, who was taken to Indiana Territory. She was forced to become an indentured servant, even though the Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery. She was sold in 1816, the same year that the Constitution of Indiana prohibited slavery and indentured servitude. In 1821, attorney Amory Kinney represented her as she fought for her freedom in the courts. After losing the case in the Circuit Court, she appealed to the Indiana Supreme Court in the case of Mary Clark v. G.W. Johnston. She won her freedom with the precedent-setting decision against indentured servitude in Indiana. The documentary, Mary Bateman Clark: A Woman of Colour and Courage, tells the story of her life and fight for freedom.