Related Research Articles

An expert witness, particularly in common law countries such as the United Kingdom, Australia, and the United States, is a person whose opinion by virtue of education, training, certification, skills or experience, is accepted by the judge as an expert. The judge may consider the witness's specialized opinion about evidence or about facts before the court within the expert's area of expertise, to be referred to as an "expert opinion". Expert witnesses may also deliver "expert evidence" within the area of their expertise. Their testimony may be rebutted by testimony from other experts or by other evidence or facts.

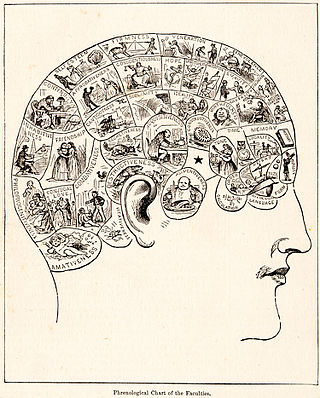

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method. Pseudoscience is often characterized by contradictory, exaggerated or unfalsifiable claims; reliance on confirmation bias rather than rigorous attempts at refutation; lack of openness to evaluation by other experts; absence of systematic practices when developing hypotheses; and continued adherence long after the pseudoscientific hypotheses have been experimentally discredited. It is not the same as junk science.

The Heidelberg Appeal, authored by Michel Salomon, was an appeal directed against the findings of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. The Heidelberg Appeal's goal was similar to the later published Leipzig Declaration. Before the publication, Fred Singer, who has initiated several petitions like the Heidelberg Appeal, and Michel Salomon, had organized a conference in Heidelberg, which led to that document. It was published on the last day of the 1992 Rio Summit, and warned against basing environmental policies on what the authors described as "pseudoscientific arguments or false and nonrelevant data." It was initiated by the tobacco and asbestos industries, to support the climate-denying Global Climate Coalition. According to SourceWatch the appeal was "a scam perpetrated by the asbestos and tobacco industries in support of the Global Climate Coalition". Both industries had no direct reason to deny global warming, but rather wanted to promote their "sound science" agenda, which basically states that industry-funded science is good science and science contradicting those science is bad science or "junk science".

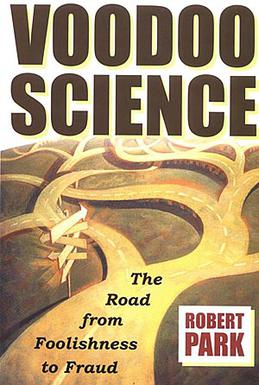

Voodoo Science: The Road from Foolishness to Fraud is a book published in 2000 by physics professor Robert L. Park, critical of research that falls short of adhering to the scientific method. Other people have used the term "voodoo science", but amongst academics it is most closely associated with Park. Park offers no explanation as to why he appropriated the word voodoo to describe the four categories detailed below. The book is critical of, among other things, homeopathy, cold fusion and the International Space Station.

Passive smoking is the inhalation of tobacco smoke, called passive smoke, secondhand smoke (SHS) or environmental tobacco smoke (ETS), by individuals other than the active smoker. It occurs when tobacco smoke diffuses into the surrounding atmosphere as an aerosol pollutant, which leads to its inhalation by nearby bystanders within the same environment. Exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke causes many of the same diseases caused by active tobacco smoking, although to a lower prevalence due to the reduced concentration of smoke that enters the airway. The health risks of secondhand smoke are a matter of scientific consensus, and have been a major motivation for smoking bans in workplaces and indoor venues, including restaurants, bars and night clubs, as well as some open public spaces.

Medical malpractice is professional negligence by act or omission by a health care provider in which the treatment provided falls below the accepted standard of practice in the medical community and causes injury or death to the patient, with most cases involving medical error. Claims of medical malpractice, when pursued in US courts, are processed as civil torts. Sometimes an act of medical malpractice will also constitute a criminal act, as in the case of the death of Michael Jackson.

In United States federal law, the Daubert standard is a rule of evidence regarding the admissibility of expert witness testimony. A party may raise a Daubert motion, a special motion in limine raised before or during trial, to exclude the presentation of unqualified evidence to the jury. The Daubert trilogy are the three United States Supreme Court cases that articulated the Daubert standard:

Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 509 U.S. 579 (1993), is a United States Supreme Court case determining the standard for admitting expert testimony in federal courts. In Daubert, the Court held that the enactment of the Federal Rules of Evidence implicitly overturned the Frye standard; the standard that the Court articulated is referred to as the Daubert standard.

Steven J. Milloy is a lawyer, lobbyist, author and former Fox News commentator. Milloy is the founder and editor of the blog junkscience.com.

The Project on Scientific Knowledge and Public Policy (SKAPP), based at the George Washington University in Washington, D.C., examines the nature of science and the ways in which it is both used and misused in government decision-making and legal proceedings. Through empirical research, conversations among scholars, and publications, SKAPP aims to enhance understanding of how knowledge is generated and interpreted. SKAPP's mission is to promote transparent decision-making based on the best available science in order to promote public safety and health.

The Advancement of Sound Science Center (TASSC), formerly The Advancement of Sound Science Coalition, was an industry-funded lobby group and crisis management vehicle, and was created in 1993 by Phillip Morris and APCO in response to a 1992 United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) report which identified secondhand smoke as a "confirmed" human carcinogen. TASSC's stated objectives were to (1) discredit the EPA report; (2) fight anti-smoking legislation; and (3) pro-actively pass legislation favourable to the tobacco industry.

In United States law, the Frye standard, Frye test, or general acceptance test is a judicial test used in some U.S. state courts to determine the admissibility of scientific evidence. It provides that expert opinion based on a scientific technique is admissible only when the technique is generally accepted as reliable in the relevant scientific community. In Daubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, 509 U.S. 579 (1993), the U.S. Supreme Court held that the Federal Rules of Evidence superseded Frye as the standard for admissibility of expert evidence in federal courts. Some states, however, still adhere to the Frye standard.

The Weinberg Group is a Washington, DC-based food and drug regulatory consulting group. Founded in 1983, the firm assists pharmaceutical and biotech companies with the "development and implementation of successful and innovative regulatory strategies" and also helps these companies to "remediate, maintain and improve their regulatory compliance." The Weinberg Group sent a memo to DuPont in 2003 recommending that the company “reshape the debate by identifying the likely known health benefits of PFOA exposure.”

Tobacco politics refers to the politics surrounding the use and distribution of tobacco.

A manufactured controversy is a contrived disagreement, typically motivated by profit or ideology, designed to create public confusion concerning an issue about which there is no substantial academic dispute. This concept has also been referred to as manufactured uncertainty.

The Center for Indoor Air Research was a tobacco industry front group established by three American tobacco companies—Philip Morris, R.J. Reynolds, and Lorillard—in Linthicum, Maryland, in 1988. The organization funded research on indoor air pollution, some of which pertained to passive smoking and some of which did not. It also funded research pertaining to causes of lung cancer other than passive smoking, such as diet. The organization disbanded in 1998 as a result of the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement.

The Game Changers is a 2018 American documentary film about athletes who follow plant-based diets.

The tobacco industry playbook, tobacco strategy or simply disinformation playbook describes a strategy devised by the tobacco industry in the 1950s to protect revenues in the face of mounting evidence of links between tobacco smoke and serious illnesses, primarily cancer. Much of the playbook is known from industry documents made public by whistleblowers or as a result of the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement. These documents are now curated by the UCSF Truth Tobacco Industry Documents project and are a primary source for much commentary on both the tobacco playbook and its similarities to the tactics used by other industries, notably the fossil fuel industry. It is possible that the playbook may even have originated with the oil industry.

Cheryl Healton is an American public health researcher who is Professor of Public Health Policy and Dean of School of Global Public Health at New York University. Her research considers public health policy surrounding tobacco control.

Richard A. Daynard is an American legal scholar. He is a University Distinguished Professor at the Northeastern University School of Law.

References

- ↑ LaFee, Scott (2006-10-22). "'Junk' food for thought". San Diego Union Tribune. Retrieved 2016-02-14.[ permanent dead link ]

- 1 2 Neff RA, Goldman LR (2005). "Regulatory parallels to Daubert: stakeholder influence, "sound science," and the delayed adoption of health-protective standards". Am J Public Health. 95 (Suppl 1): S81–91. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.044818. hdl: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.044818 . PMID 16030344. S2CID 10175577.

- ↑ Dariusz Jemielniak; Aleksandra Przegalinska (2020). Collaborative Society. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0262356459.

- ↑ Kaufman, Allison B.; Kaufman, James C. (2019-03-12). Pseudoscience: The Conspiracy Against Science. MIT Press. p. 471. ISBN 978-0-262-53704-9.

Pseudoscience is different from junk science...

- 1 2 Fang, Ferric C.; Casadevall, Arturo (2023-10-31). Thinking about Science: Good Science, Bad Science, and How to Make It Better. John Wiley & Sons. p. 172. ISBN 978-1-68367-434-4.

- 1 2 3 Garfinkle, David; Garfinkle, Richard (2009-05-15). Three Steps to the Universe: From the Sun to Black Holes to the Mystery of Dark Matter. University of Chicago Press. p. 255. ISBN 978-0-226-28349-4.

- 1 2 3 Lilienfeld, Scott O.; Lynn, Steven Jay; Lohr, Jeffrey M. (2014-10-17). Science and Pseudoscience in Clinical Psychology. Guilford Publications. p. 282. ISBN 978-1-4625-1759-6.

- ↑ "Report of the Tort Policy Working Group on the causes, extent and policy implications of the current crisis in insurance availability and affordability" (Rep. No. 027-000-01251-5). (1986, February). Washington, D.C.: Superintendent of Documents, US Government Printing Office. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No. ED274437) p. 39:

Another way in which causation often is undermined—also an increasingly serious problem in toxic tort cases—is the reliance by judges and juries on non-credible scientific or medical testimony, studies or opinions. It has become all too common for 'experts' or 'studies' on the fringes of or even well beyond the outer parameters of mainstream scientific or medical views to be presented to juries as valid evidence from which conclusions may be drawn. The use of such invalid scientific evidence (commonly referred to as 'junk science') has resulted in findings of causation which simply cannot be justified or understood from the standpoint of the current state of credible scientific and medical knowledge. Most importantly, this development has led to a deep and growing cynicism about the ability of tort law to deal with difficult scientific and medical concepts in a principled and rational way.

- ↑ Roberts, L. (1989). "Global warming: Blaming the sun". Science. 246 (4933): 992–993. Bibcode:1989Sci...246..992R. doi:10.1126/science.246.4933.992. PMID 17806372.

- ↑ General Electric Company v. Robert K. Joiner, No. 96–188, slip op. at 4 (U.S. December 15, 1997).

- ↑ Huber, P. W. (1991). Galileo's revenge: Junk science in the courtroom (2001 ed.). New York: Basic Books. p. 191.

- ↑ Charles H. Sanderson v. Culligan International Company , No. 04-3253, slip op. at 3 (7th Cir. July 11, 2005).

- ↑ Ehrlich, P. R.; Wolff, G.; Daily, G. C.; Hughes, J. B.; Daily, S.; Dalton, M.; et al. (1999). "Knowledge and the environment". Ecological Economics. 30 (2): 267–284. doi: 10.1016/s0921-8009(98)00130-x .

- ↑ Pedynowski, D (2003). "Toward a more 'Reflexive Environmentalism': Ecological knowledge and advocacy in the Crown of the Continent Ecosystem". Society and Natural Resources. 16 (9): 807–825. doi:10.1080/08941920309168. S2CID 144702458.

- ↑ Agin 2006.

- ↑ Agin 2006, p. 39.

- ↑ Agin 2006, p. 63.

- ↑ Agin 2006, p. 249.

- 1 2 Kaufman, Allison B.; Kaufman, James C. (2019-03-12). Pseudoscience: The Conspiracy Against Science. MIT Press. p. 292. ISBN 978-0-262-53704-9.

- ↑ "Smoked Out: Pundit For Hire", published in The New Republic, accessed 24 November 2010.

- ↑ Rampton, Sheldon; Stauber, John (2000). "How Big Tobacco Helped Create 'the Junkman'" (PDF). PR Watch. Vol. 7, no. 3. Center for Media and Democracy.

- ↑ Activity Report, R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co., December 1996; describes R.J.R. Tobacco's direct input into Milloy's junk science website. Legacy Tobacco Documents Library at the University of California, San Francisco. Accessed 5 October 2006.

- 1 2 Minutes of a meeting in which Philip Morris Tobacco discusses the inception of the "Whitecoat Project" Archived 2007-10-13 at the Wayback Machine . Accessed 5 October 2006.

- ↑ Michaels, David (2008). Doubt is Their Product: How Industry's Assault on Science Threatens Your Health. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 3. ISBN 978-0195300673.

- ↑ Michaels, David (2005). "Scientific Evidence and Public Policy". American Journal of Public Health. 95 (S1): 5–7. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2005.065599. hdl: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065599 . PMID 16030339.

- ↑ "Paul Cameron". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ↑ Herek, Gregory M. (1997–2007). "Facts About Homosexuality and Child Molestation". psychology.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- 1 2 "Paul Cameron's Falsehoods Cited By Anti-Gay Sympathizers". Southern Poverty Law Center. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ↑ "Sound science initiative". ASLO Bulletin. 7 (1): 13. Winter 1998.

- ↑ "Sound Science for Endangered Species" (PDF). Science and Technology in Congress. September 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 24, 2006. Retrieved November 12, 2006.