Alexios I Komnenos, Latinized Alexius I Comnenus, was Byzantine emperor from 1081 to 1118. Although he was not the first emperor of the Komnenian dynasty, it was during his reign that the Komnenos family came to full power and initiated a hereditary succession to the throne. Inheriting a collapsing empire and faced with constant warfare during his reign against both the Seljuq Turks in Asia Minor and the Normans in the western Balkans, Alexios was able to curb the Byzantine decline and begin the military, financial, and territorial recovery known as the Komnenian restoration. His appeals to Western Europe for help against the Turks was the catalyst that sparked the First Crusade.

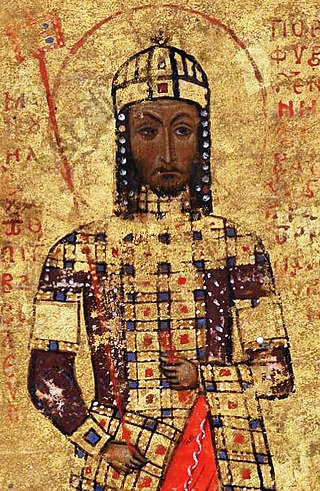

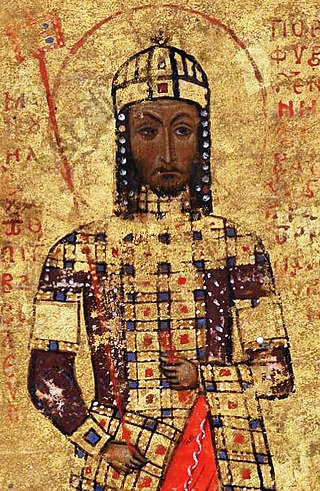

Manuel I Komnenos, Latinized Comnenus, also called Porphyrogennetos, was a Byzantine emperor of the 12th century who reigned over a crucial turning point in the history of Byzantium and the Mediterranean. His reign saw the last flowering of the Komnenian restoration, during which the Byzantine Empire had seen a resurgence of its military and economic power and had enjoyed a cultural revival.

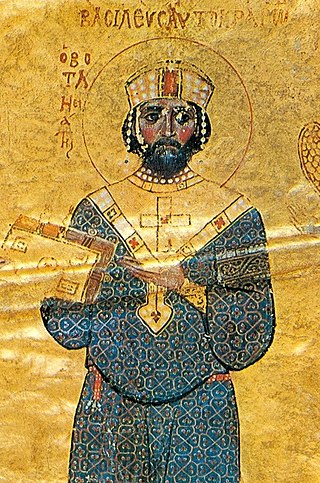

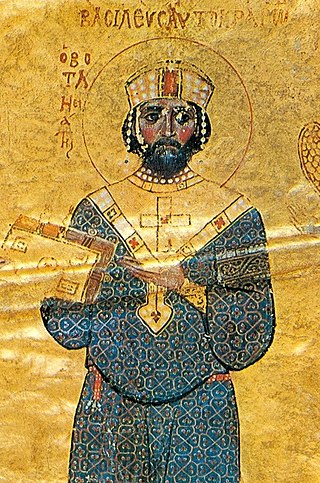

Nikephoros III Botaneiates, Latinized as Nicephorus III Botaniates, was Byzantine Emperor from 7 January 1078 to 1 April 1081. He was born in 1002, and became a general during the reign of Byzantine Emperor Constantine IX Monomachos, serving in the Pecheneg revolt of 1048–1053. His actions in guiding his forces away from the Pechenegs following the Battle of Zygos Pass, in which they suffered eleven days of harassment before finally reaching the Byzantine city of Adrianople, attracted the attention of fellow officers, and he received the title of magistros as a reward. Nikephoros served in the revolt of Isaac I Komnenos against the Byzantine Emperor Michael VI Bringas, leading forces at the decisive Battle of Petroe. Under the Emperor Constantine X Doukas he was made doux of Thessalonica, where he remained until c. 1065, when he was reassigned as doux of Antioch. While doux of Antioch, he repelled numerous incursions from the Emirate of Aleppo. When Constantine X died in 1067, his wife, Empress Eudokia Makrembolitissa, considered taking Nikephoros as husband and emperor but instead chose Romanos IV Diogenes. The need for an immediate successor was made pressing by the constant Seljuk raids into Byzantine Anatolia, and Eudokia, Patriarch John VIII of Constantinople, and the Byzantine Senate agreed that their top priority was the defense of the empire and that they needed an emperor to lead troops to repel the Turks. Nikephoros was the favorite candidate of the senate, but was in the field leading troops in Antioch and was still married. Romanos, once chosen to be emperor, exiled Nikephoros to his holdings in the Anatolic Theme, where he remained until he was brought out of retirement by the Emperor Michael VII and made kouropalates and governor of the Anatolic Theme.

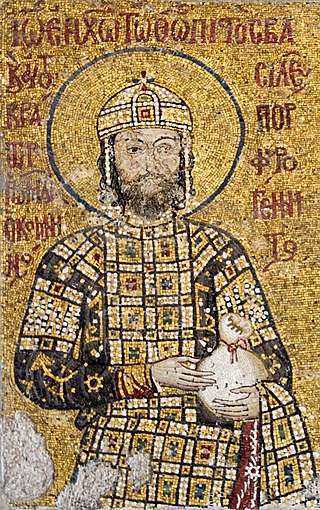

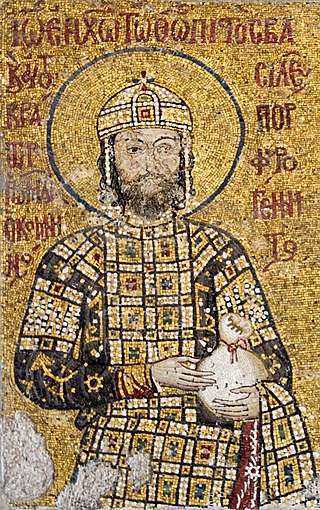

John II Komnenos or Comnenus was Byzantine emperor from 1118 to 1143. Also known as "John the Beautiful" or "John the Good", he was the eldest son of Emperor Alexios I Komnenos and Irene Doukaina and the second emperor to rule during the Komnenian restoration of the Byzantine Empire. As he was born to a reigning emperor, he had the status of a porphyrogennetos. John was a pious and dedicated monarch who was determined to undo the damage his empire had suffered following the Battle of Manzikert, half a century earlier.

The Battle of Manzikert or Malazgirt was fought between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Empire on 26 August 1071 near Manzikert, theme of Iberia. The decisive defeat of the Byzantine army and the capture of the Emperor Romanos IV Diogenes played an important role in undermining Byzantine authority in Anatolia and Armenia, and allowed for the gradual Turkification of Anatolia. Many Turks, travelling westward during the 11th century, saw the victory at Manzikert as an entrance to Asia Minor.

The Battle of Myriokephalon was a battle between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Turks in Phrygia in the mountains west of Iconium (Konya) in southwestern Turkey on 17 September 1176. The battle was a strategic reverse for the Byzantine forces, who were ambushed when moving through a mountain pass.

The Treaty of Devol was an agreement made in 1108 between Bohemond I of Antioch and Byzantine Emperor Alexios I Komnenos, in the wake of the First Crusade. It is named after the Byzantine fortress of Devol. Although the treaty was not immediately enforced, it was intended to make the Principality of Antioch a vassal state of the Byzantine Empire.

The House of Komnenos, Latinized as Comnenus, was a Byzantine Greek noble family who ruled the Byzantine Empire in the 11th and 12th centuries. The first reigning member, Isaac I Komnenos, ruled from 1057 to 1059. The family returned to power under Alexios I Komnenos in 1081 who established their rule for the following 104 years until it ended with Andronikos I Komnenos in 1185. In the 13th century, they founded and ruled the Empire of Trebizond, a Byzantine rump state from 1204 to 1461. At that time, they were commonly referred to as Grand Komnenoi, a style that was officially adopted and used by George Komnenos and his successors. Through intermarriages with other noble families, notably the Doukas, Angelos, and Palaiologos, the Komnenos name appears among most of the major noble houses of the late Byzantine world.

The Battle of Levounion was the first decisive Byzantine victory of the Komnenian restoration. On April 29, 1091, an invading force of Pechenegs was crushed by the combined forces of the Byzantine Empire under Alexios I Komnenos and his Cuman allies.

The Byzantine army of the Komnenian era or Komnenian army was a force established by Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos during the late 11th/early 12th century. It was further developed during the 12th century by his successors John II Komnenos and Manuel I Komnenos. From necessity, following extensive territorial loss and a near disastrous defeat by the Normans of southern Italy at Dyrrachion in 1081, Alexios constructed a new army from the ground up. This new army was significantly different from previous forms of the Byzantine army, especially in the methods used for the recruitment and maintenance of soldiers. The army was characterised by an increased reliance on the military capabilities of the immediate imperial household, the relatives of the ruling dynasty and the provincial Byzantine aristocracy. Another distinctive element of the new army was an expansion of the employment of foreign mercenary troops and their organisation into more permanent units. However, continuity in equipment, unit organisation, tactics and strategy from earlier times is evident. The Komnenian army was instrumental in creating the territorial integrity and stability that allowed the Komnenian restoration of the Byzantine Empire. It was deployed in the Balkans, Italy, Hungary, Russia, Anatolia, Syria, the Holy Land and Egypt.

The Byzantine Empire experienced several cycles of growth and decay over the course of nearly a thousand years, including major losses during the early Muslim conquests of the 7th century.

The Byzantine–Seljuk wars were a series of conflicts in the Middle Ages between the Byzantine Empire and the Seljuk Empire. They shifted the balance of power in Asia Minor and Syria from the Byzantines to the Seljuk dynasty. Riding from the steppes of Central Asia, the Seljuks replicated tactics practiced by the Huns hundreds of years earlier against a similar Roman opponent but now combining it with new-found Islamic zeal. In many ways, the Seljuk resumed the conquests of the Muslims in the Byzantine–Arab Wars initiated by the Rashidun, Umayyad and Abbasid Caliphates in the Levant, North Africa and Asia Minor.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the Komnenos dynasty for a period of 104 years, from 1081 to about 1185. The Komnenian period comprises the reigns of five emperors, Alexios I, John II, Manuel I, Alexios II and Andronikos I. It was a period of sustained, though ultimately incomplete, restoration of the military, territorial, economic and political position of the Byzantine Empire.

Nikephoros Melissenos, Latinized as Nicephorus Melissenus, was a Byzantine general and aristocrat. Of distinguished lineage, he served as a governor and general in the Balkans and Asia Minor in the 1060s. In the turbulent period after the Battle of Manzikert in 1071, when several generals tried to seize the throne for themselves, Melissenos remained loyal to Michael VII Doukas and was exiled by his successor Nikephoros III Botaneiates. In 1080–1081, with Turkish aid, he seized control of what remained of Byzantine Asia Minor and proclaimed himself emperor against Botaneiates. After the revolt of his brother-in-law Alexios I Komnenos, however, which succeeded in taking Constantinople, he submitted to him, accepting the rank of Caesar and the governance of Thessalonica. He remained loyal to Alexios thereafter, participating in most Byzantine campaigns of the period 1081–1095 in the Balkans at the emperor's side. He died on 17 November 1104.

George Palaiologos or Palaeologus was a Byzantine aristocrat and general. One of the earliest known ancestors of the Palaiologos dynasty, he was a capable military commander who played a critical role in helping his brother-in-law Alexios I Komnenos seize the throne in 1081. In subsequent year he played an important role in Alexios' campaigns, especially the Battle of Dyrrhachium against the Italo-Normans or the Battle of Levounion against the Pechenegs, and was a major source used by Anna Komnene in her Alexiad.

This history of the Byzantine Empire covers the history of the Eastern Roman Empire from late antiquity until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD. Several events from the 4th to 6th centuries mark the transitional period during which the Roman Empire's east and west divided. In 285, the emperor Diocletian partitioned the Roman Empire's administration into eastern and western halves. Between 324 and 330, Constantine I transferred the main capital from Rome to Byzantium, later known as Constantinople and Nova Roma. Under Theodosius I, Christianity became the Empire's official state religion and others such as Roman polytheism were proscribed. Finally, under the reign of Heraclius, the Empire's military and administration were restructured and adopted Greek for official use instead of Latin. Although the Roman state continued, some historians choose to distinguish the Byzantine Empire from the earlier Roman Empire due to the imperial seat moving from Rome to Byzantium, the Empire’s integration of Christianity, and the predominance of Greek instead of Latin.

John Komnenos Vatatzes, or simply John Komnenos or John Vatatzes in the sources, was a major military and political figure in the Byzantine Empire during the reigns of Manuel I Komnenos and Alexios II Komnenos. He was born c. 1132, and died of natural causes during a rebellion he raised against Andronikos I Komnenos in 1182.

Byzantine Anatolia refers to the peninsula of Anatolia during the rule of the Byzantine Empire. Anatolia was of vital importance to the empire following the Muslim invasion of Syria and Egypt during the reign of the Byzantine Emperor Heraclius in the years 634–645 AD. Over the next two hundred and fifty years, the region suffered constant raids by Arab Muslim forces raiding mainly from the cities of Antioch, Tarsus, and Aleppo near the Anatolian borders. However, the Byzantine Empire maintained control over the Anatolian peninsula until the High Middle Ages, when imperial authority in the area began to collapse.

The Byzantine Empire was ruled by emperors of the Doukas dynasty between 1059 and 1081. There are six emperors and co-emperors of this period: the dynasty's founder, Emperor Constantine X Doukas, his brother John Doukas, katepano and later Caesar, Romanos IV Diogenes, Constantine's son Michael VII Doukas, Michael's son and co-emperor Constantine Doukas, and finally Nikephoros III Botaneiates, who claimed descent from the Phokas family.