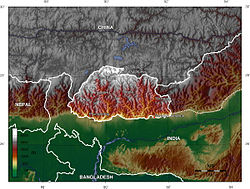

Bhutan is a sovereign country at the crossroads of East Asia and South Asia, located towards the eastern extreme of the Himalayas mountain range. It is fairly evenly sandwiched between the sovereign territory of two nations: first, the People's Republic of China (PRC) on the north and northwest. There are approximately 477 kilometres (296 mi) of border with the country's Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), or simply Tibet. The second nation is the Republic of India on the south, southwest, and east; there are approximately 659 kilometres (409 mi) with the states of Arunachal Pradesh, Assam, West Bengal, and Sikkim, in clockwise order from the kingdom. Bhutan's total borders amount to approximately 1,139 kilometres (708 mi). The Indian state of Sikkim to the west, the India to the south, and the Assam state of India to the southeast are other close neighbours; the former two are separated by only very small stretches of Indian territory.

Gasa District or Gasa Dzongkhag is one of the 20 dzongkhags (districts) comprising Bhutan. The capital of Gasa District is Gasa Dzong near Gasa. It is located in the far north of the county and spans the Middle and High regions of the Tibetan Himalayas. The dominant language of the district is Dzongkha, which is the national language. Related languages, Layakha and Lunanakha, are spoken by semi-nomadic communities in the north of the district. The People's Republic of China claims the northern part of Gasa District.

A moraine-dammed lake, occurs when the terminal moraine has prevented some meltwater from leaving the valley. When a glacier retreats, there is a space left over between the retreating glacier and the piece that stayed intact which holds leftover debris (moraine). Meltwater from both glaciers seep into this space creating a ribbon-shaped lake due to the pattern of ice melt. This ice melt may cause a glacier lake outburst flood, leading to severe damage to the environment and communities nearby. Examples of moraine-dammed lakes include:

The Layap are an indigenous people inhabiting the high mountains of northwest Bhutan in the village of Laya, in the Gasa District, at an altitude of 3,850 metres (12,630 ft), just below the Tsendagang peak. Their population in 2003 stood at 1,100. They speak Layakha, a Tibeto-Burman language. Layaps refer to their homeland as Be-yul – "the hidden land."

Punakha is the administrative centre of Punakha dzongkhag, one of the 20 districts of Bhutan. Punakha was the capital of Bhutan and the seat of government until 1955, when the capital was moved to Thimphu. It is about 72 km away from Thimphu, and it takes about 3 hours by car from the capital. Unlike Thimphu, it is quite warm in winter and hot in summer. It is located at an elevation of 1,200 metres above sea level, and rice is grown as the main crop along the river valleys of two main rivers of Bhutan, the Pho Chu and Mo Chu. Dzongkha is widely spoken in this district.

A glacial lake outburst flood (GLOF) is a type of outburst flood caused by the failure of a dam containing a glacial lake. An event similar to a GLOF, where a body of water contained by a glacier melts or overflows the glacier, is called a jökulhlaup. The dam can consist of glacier ice or a terminal moraine. Failure can happen due to erosion, a buildup of water pressure, an avalanche of rock or heavy snow, an earthquake or cryoseism, volcanic eruptions under the ice, or massive displacement of water in a glacial lake when a large portion of an adjacent glacier collapses into it.

Jakar is a town in the central-eastern region of Bhutan. It is the district capital of Bumthang District and the location of Jakar Dzong, the regional dzong fortress. The name Jakar roughly translates as "white bird" in reference to its foundation myth, according to which a roosting white bird signalled the proper and auspicious location to found a monastery around 1549.

Wangdue Phodrang is a town and capital of Wangdue Phodrang District in central Bhutan. It is located in Thedtsho Gewog. Khothang Rinchenling

The Bhutan Observer was Bhutan's first private bilingual newspaper. It was launched as a private limited company by parent company Bhutan Media Services (BMS), and began publishing on June 2, 2006, in Thimphu. Its Dzongkha edition was called Druk Nelug, and the newspaper maintained an online service in English until 2013.

The Jigme Dorji National Park (JDNP), named after the late Jigme Dorji Wangchuck, is the second-largest National Park of Bhutan.

The Punakha Dzong, also known as Pungthang Dewa chhenbi Phodrang, is the administrative centre of Punakha District in Punakha, Bhutan. Constructed by Ngawang Namgyal, 1st Zhabdrung Rinpoche, in 1637–38, it is the second oldest and second-largest dzong in Bhutan and one of its most majestic structures. The dzong houses the sacred relics of the southern Drukpa Lineage of the Kagyu school of Tibetan Buddhism, including the Rangjung Kharsapani and the sacred remains of Ngawang Namgyal and the tertön Pema Lingpa.

The glaciers in Bhutan, which covers about 3 percent of the total surface area, are responsible for feeding all rivers of Bhutan except the Amochu and Nyere Amachu.

Thrumshing La, also called Thrumshingla Pass and Donga Pass,, is the second-highest mountain pass in Bhutan, connecting its central and eastern regions across the otherwise impregnable Donga range that has separated populations for centuries. It is located on a bend of the Lateral Road at the border of Bumthang District and Mongar District, along the border with Lhuntse District to the east. The Lateral Road bisects Thrumshingla National Park, named after the pass. The World Wildlife Fund also maintains operations in the park.

HIV/AIDS in Bhutan remains a relatively rare disease among its population. It has, however, grown into an issue of national concern since Bhutan's first reported case in 1993. Despite preemptive education and counseling efforts, the number of reported HIV/AIDS cases has climbed since the early 1990s. This prompted increased government efforts to confront the spread of the disease through mainstreaming sexually transmitted disease (STD) and HIV prevention, grassroots education, and the personal involvement of the Bhutanese royal family in the person of Queen Mother Sangay Choden.

Among Bhutan's most pressing environmental issues are traditional firewood collection, crop and flock protection, and waste disposal, as well as modern concerns such as industrial pollution, wildlife conservation, and climate change that threaten Bhutan's population and biodiversity. Land and water use have also become matters of environmental concern in both rural and urban settings. In addition to these general issues, others such as landfill availability and air and noise pollution are particularly prevalent in relatively urbanized and industrialized areas of Bhutan. In many cases, the least financially and politically empowered find themselves the most affected by environmental issues.

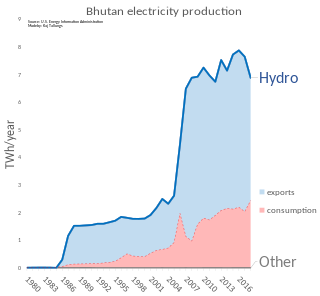

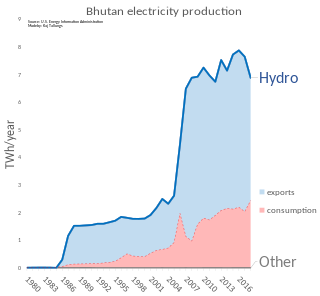

Energy in Bhutan has been a primary focus of development in the kingdom under its Five-Year Plans. In cooperation with India, Bhutan has undertaken several hydroelectric projects whose output is traded between the countries. Though Bhutan's many hydroelectric plants provide energy far in excess of its needs in the summer, dry winters and increased fuel demand makes the kingdom a marginal net importer of energy from India.

The mountains of Bhutan are some of the most prominent natural geographic features of the kingdom. Located on the southern end of the Eastern Himalaya, Bhutan has one of the most rugged mountain terrains in the world, whose elevations range from 160 metres (520 ft) to more than 7,000 metres (23,000 ft) above sea level, in some cases within distances of less than 100 kilometres (62 mi) of each other. Bhutan's highest peak, at 7,570 metres (24,840 ft) above sea level, is north-central Gangkhar Puensum, close to the border with Tibet; the third highest peak, Jomolhari, overlooking the Chumbi Valley in the west, is 7,314 metres (23,996 ft) above sea level; nineteen other peaks exceed 7,000 metres (23,000 ft). Weather is extreme in the mountains: the high peaks have perpetual snow, and the lesser mountains and hewn gorges have high winds all year round, making them barren brown wind tunnels in summer, and frozen wastelands in winter. The blizzards generated in the north each winter often drift southward into the central highlands.

Motithang Higher Secondary School is a government high school in the capital city of Thimphu, Bhutan. It was established in the year 1975. Motithang translates to The Meadow of Pearls in English.