Related Research Articles

Watership Down is an adventure novel by English author Richard Adams, published by Rex Collings Ltd of London in 1972. Set in Hampshire in southern England, the story features a small group of rabbits. Although they live in their natural wild environment, with burrows, they are anthropomorphised, possessing their own culture, language, proverbs, poetry, and mythology. Evoking epic themes, the novel follows the rabbits as they escape the destruction of their warren and seek a place to establish a new home, encountering perils and temptations along the way.

In linguistics, a neologism is any newly formed word, term, or phrase that nevertheless has achieved popular or institutional recognition and is becoming accepted into mainstream language. Most definitively, a word can be considered a neologism once it is published in a dictionary.

The black-headed gull is a small gull that breeds in much of the Palearctic including Europe and also in coastal eastern Canada. Most of the population is migratory and winters further south, but some birds reside in the milder westernmost areas of Europe. The species also occurs in smaller numbers in northeastern North America, where it was formerly known as the common black-headed gull.

In linguistics, a nonce word—also called an occasionalism—is any word (lexeme), or any sequence of sounds or letters, created for a single occasion or utterance but not otherwise understood or recognized as a word in a given language. Nonce words have a variety of functions and are most commonly used for humor, poetry, children's literature, linguistic experiments, psychological studies, and medical diagnoses, or they arise by accident.

A cant is the jargon or language of a group, often employed to exclude or mislead people outside the group. It may also be called a cryptolect, argot, pseudo-language, anti-language or secret language. Each term differs slightly in meaning; their uses are inconsistent. Richard Rorty defines cant by saying that "'Cant', in the sense in which Samuel Johnson exclaims, 'Clear your mind of cant,' means, in other words, something like that which 'people usually say without thinking, the standard thing to say, what one normally says'." In Heideggerian terms it is what "das Man" says.

Tales from Watership Down is a collection of 19 short stories by Richard Adams, published in 1996 as a follow-up to Adams's highly successful 1972 novel about rabbits, Watership Down. It consists of a number of short stories of rabbit mythology, followed by several chapters featuring many of the characters introduced in the earlier book. Like its predecessor, Tales from Watership Down features epigraphs at the beginning of each chapter and a Lapine glossary.

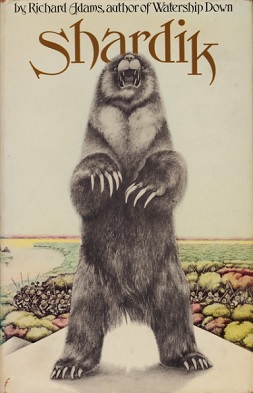

Shardik is a 1974 fantasy novel by Richard Adams. Shardik is his second novel, and first of two novels set in the fictional Beklan Empire. The events revolve around the discovery, capture and military and symbolic uses made of an incredibly large bear, called "Lord Shardik" by those who subscribe to a set of religious beliefs in the novel.

Watership Down is a 1978 British animated adventure-drama film, written, produced and directed by Martin Rosen and based on the 1972 novel by Richard Adams. It was financed by a consortium of British financial institutions and was distributed by Cinema International Corporation in the United Kingdom. Released on 19 October 1978, the film was an immediate success and it became the sixth-most popular film of 1979 at the UK box office.

Watership Down is a hill or a down at Ecchinswell in the civil parish of Ecchinswell, Sydmonton and Bishops Green in the English county of Hampshire, as part of the Hampshire Downs. It rises fairly steeply on its northern flank, but to the south the slope is much gentler. The summit is 778 ft (237 m) above sea level, one of the highest points in Hampshire.

Parataxis is a literary technique, in writing or speaking, that favors short, simple sentences, without conjunctions or with the use of coordinating, but not with subordinating conjunctions. It contrasts with syntaxis and hypotaxis.

Maia is a fantasy novel by Richard Adams, published in 1984. It is set in the Beklan Empire, the fictional world of Adams's 1974 novel Shardik, to which it stands as a loose prequel, taking place a few years earlier.

Martin Gerald Rosen is an American-British filmmaker and theater producer. He directed the animated film adaptations of Watership Down (1978) and The Plague Dogs (1982), both from the Richard Adams novels.

Watership Down is an animated fantasy children's television series, adapted from the 1972 novel of the same name by Richard Adams. The second adaptation of the novel, it was produced by UK's Alltime Entertainment and Canada's Decode Entertainment in association with Martin Rosen, with the participation of the Canadian Television Fund, the Canadian Film or Video Production Tax Credit and the Ontario Film and Television Tax Credit from the Government of Ontario.

Lapine may refer to:

Richard George Adams was an English novelist whose works include Watership Down, Maia, Shardik and The Plague Dogs. He studied modern history at Oxford before serving in the British Army during World War II. After completing his studies, he joined the British Civil Service. In 1974, two years after Watership Down was published, Adams became a full-time author.

An animal tale or beast fable generally consists of a short story or poem in which animals talk. They may exhibit other anthropomorphic qualities as well, such as living in a human-like society. It is a traditional form of allegorical writing.

In linguistics, according to J. Richard et al., (2002), an error is the use of a word, speech act or grammatical items in such a way that it seems imperfect and significant of an incomplete learning (184). It is considered by Norrish as a systematic deviation which happens when a learner has not learnt something, and consistently gets it wrong. However, the attempts made to put the error into context have always gone hand in hand with either [language learning and second-language acquisition] processe, Hendrickson (1987:357) mentioned that errors are ‘signals’ that indicate an actual learning process taking place and that the learner has not yet mastered or shown a well-structured [linguistic competence|competence] in the target language.

Syntactic bootstrapping is a theory in developmental psycholinguistics and language acquisition which proposes that children learn word meanings by recognizing syntactic categories and the structure of their language. It is proposed that children have innate knowledge of the links between syntactic and semantic categories and can use these observations to make inferences about word meaning. Learning words in one's native language can be challenging because the extralinguistic context of use does not give specific enough information about word meanings. Therefore, in addition to extralinguistic cues, conclusions about syntactic categories are made which then lead to inferences about a word's meaning. This theory aims to explain the acquisition of lexical categories such as verbs, nouns, etc. and functional categories such as case markers, determiners, etc.

Fall of Efrafa was a British crust punk band formed in Brighton, England in 2005. They disbanded in 2009 after completing a trilogy of concept albums – Owsla (2006), Elil (2007), and Inlé (2009) – inspired by the mythology of the 1972 novel Watership Down.

Watership Down is a CGI-animated adventure fantasy drama television miniseries directed by Noam Murro. It is based on the 1972 novel of the same name by Richard Adams and adapted by Tom Bidwell. It was released on 22 December 2018 in the United Kingdom and internationally on Netflix the next day. The BBC broadcast comprised two back-to-back episodes per day.

References

- 1 2 Henning, Jeffrey. "Lapine: The Language Of Watership Down". Langmaker . Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 23 January 2015.

- 1 2 3 Rogers, Stephen D. (2011). "Lapine". The Dictionary of Made-Up Languages. Adams Media. pp. 125–126. ISBN 9781440530401.

- ↑ Adams, Richard (December 2014). "Richard Adams reddit AMA - December 2014". Reddit (via Interviewly.com). Archived from the original on 2017-01-03. Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- ↑ Adamsrichard (2013-09-25). "I am Richard Adams, author of Watership Down, Shardik, and other novels. AMA!". r/IAmA. Retrieved 2023-12-30.

- ↑ Adams, Richard (2005). "Introduction". Watership Down . Scribner. p. xiv. ISBN 978-0-7432-7770-9.

- ↑ Levy, Keren (19 December 2013). "Watership Down by Richard Adams: A tale of courage, loyalty, language". The Guardian . Retrieved 1 February 2015.

- 1 2 Hickman, Matt. "7 fictional languages from literature and film that you can learn". Mother Nature Network . Archived from the original on 21 October 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- 1 2 Cain, Stephen (2006). "Watership Down". Encyclopedia of Fictional and Fantastic Languages. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 211–212. ISBN 9780313021930.

- 1 2 Oltermann, Philip (26 August 2015). "The rabbit language of Watership Down helped me make the leap into English". The Guardian . Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- 1 2 3 Murray, Thomas E. (1985). "Lapine Lingo in American English: Silflay". American Speech . 60 (4): 372–375. doi:10.2307/454919. ISSN 0003-1283. JSTOR 454919.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Corder, S Pit (17 August 2016). "The Language of Kehaar". RELC Journal . 8 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1177/003368827700800101. ISSN 0033-6882. S2CID 145776871.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Valdman, Albert (January 1981). "Sociolinguistic Aspects of Foreigner Talk" (PDF). International Journal of the Sociology of Language (28): 41–52. doi:10.1515/ijsl.1981.28.41. hdl: 2022/23306 . ISSN 0165-2516. S2CID 143959806.

- 1 2 Adams, Richard (2005). "Lapine Glossary". Watership Down . Scribner. pp. 475–476. ISBN 978-0-7432-7770-9.

- 1 2 Jensen, K. Thor. "11 Fake Languages that are Super Easy to Learn". Geek.com . Archived from the original on 26 April 2016. Retrieved 11 June 2019.

- ↑ Jemmer, P W (2014). Studia Aleolinguistica: An in-depth study of linguistic 'subcreation'. Enflame Newcastle Number 4. NewPhilSoc. ISBN 9781907926167.

- ↑ Jemmer, Patrick. "Aleolinguisics: Creative Language Development". Jimdo. Retrieved 1 May 2017.