Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Confucianism developed from teachings of the Chinese philosopher Confucius (551–479 BCE), during a time that was later referred to as the Hundred Schools of Thought era. Confucius considered himself a transmitter of cultural values inherited from the Xia (c. 2070–1600 BCE), Shang (c. 1600–1046 BCE) and Western Zhou dynasties (c. 1046–771 BCE). Confucianism was suppressed during the Legalist and autocratic Qin dynasty (221–206 BCE), but survived. During the Han dynasty, Confucian approaches edged out the "proto-Taoist" Huang–Lao as the official ideology, while the emperors mixed both with the realist techniques of Legalism.

Chinese philosophy originates in the Spring and Autumn period and Warring States period, during a period known as the "Hundred Schools of Thought", which was characterized by significant intellectual and cultural developments. Although much of Chinese philosophy begun in the Warring States period, elements of Chinese philosophy have existed for several thousand years. Some can be found in the I Ching, an ancient compendium of divination, which dates back to at least 672 BCE.

Confucius, born Kong Qiu (孔丘) was a Chinese philosopher of the Spring and Autumn period who is traditionally considered the paragon of Chinese sages. Confucius's teachings and philosophy underpin the East Asian culture and society, and remain influential across China and East Asia to this day. His philosophical teachings, called Confucianism, emphasized personal and governmental morality, correctness of social relationships, justice, kindness, sincerity, and a ruler's responsibilities to lead by virtue.

Chinese classic texts or canonical texts or simply dianji (典籍) refers to the Chinese texts which originated before the imperial unification by the Qin dynasty in 221 BC, particularly the "Four Books and Five Classics" of the Neo-Confucian tradition, themselves a customary abridgment of the "Thirteen Classics". All of these pre-Qin texts were written in either Old or Classical Chinese. All three canons are collectively known as the Classics.

Mencius ; born Meng Ke ; or Mengzi was a Chinese Confucian philosopher who has often been described as the "second Sage" (亞聖), that is, second to Confucius himself. He is part of Confucius' fourth generation of disciples. Mencius inherited Confucius' ideology and developed it further. Living during the Warring States period, he is said to have spent much of his life travelling around the states offering counsel to different rulers. Conversations with these rulers form the basis of the Mencius, which would later be canonised as a Confucian classic.

The Great Learning or Daxue was one of the "Four Books" in Confucianism attributed to one of Confucius' disciples, Zengzi. The Great Learning had come from a chapter in the Book of Rites which formed one of the Five Classics. It consists of a short main text of the teachings of Confucius transcribed by Zengzi and then ten commentary chapters supposedly written by Zengzi. The ideals of the book were attributed to Confucius, but the text was written by Zengzi after his death.

Zhu Xi, formerly romanized Chu Hsi, was a Chinese calligrapher, historian, philosopher, poet, and politician during the Song dynasty. Zhu was influential in the development of Neo-Confucianism. He contributed greatly to Chinese philosophy and fundamentally reshaped the Chinese worldview. His works include his editing of and commentaries to the Four Books, his writings on the process of the "investigation of things", and his development of meditation as a method for self-cultivation.

The Analects, also known as the Sayings of Confucius, is an ancient Chinese philosophical text composed of sayings and ideas attributed to Confucius and his contemporaries, traditionally believed to have been compiled by his followers. There is consensus among scholars that large parts of it were written during the Warring States period, and that it achieved its final form during the mid-Han dynasty. By the early Han dynasty the Analects was considered merely a "commentary" on the Five Classics, but the status of the Analects grew to be one of the central texts of Confucianism by the end of that dynasty.

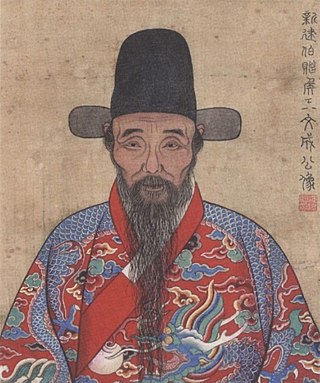

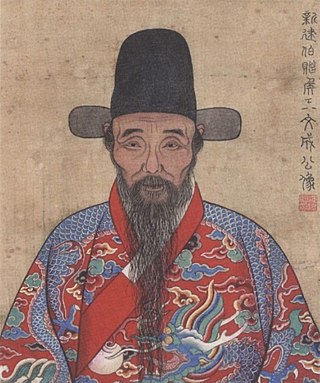

Korean Confucianism is the form of Confucianism that emerged and developed in Korea. One of the most substantial influences in Korean intellectual history was the introduction of Confucian thought as part of the cultural influence from China.

Neo-Confucianism is a moral, ethical, and metaphysical Chinese philosophy influenced by Confucianism, which originated with Han Yu (768–824) and Li Ao (772–841) in the Tang dynasty, and became prominent during the Song and Ming dynasties under the formulations of Zhu Xi (1130–1200). After the Mongol conquest of China in the thirteenth century, Chinese scholars and officials restored and preserved neo-Confucianism as a way to safeguard the cultural heritage of China.

The Doctrine of the Mean or Zhongyong is one of the Four Books of classical Chinese philosophy and a central doctrine of Confucianism. The text is attributed to Zisi, the only grandson of Confucius. It was originally a chapter in the Classic of Rites.

Wang Shouren, courtesy name Bo'an, art name Yangmingzi, usually referred to as Wang Yangming, was a Chinese calligrapher, general, philosopher, politician, and writer during the Ming dynasty. After Zhu Xi, he is commonly regarded as the most important Neo-Confucian thinker, for his interpretations of Confucianism that denied the rationalist dualism of the orthodox philosophy of Zhu Xi. Wang and Lu Xiangshan are regarded as the founders as the Lu–Wang school, or the School of the Mind.

Filial piety is the virtue of exhibiting the proper love and respect for one's parents, elders, and ancestors, particularly within the context of Confucian, Chinese Buddhist, and Daoist ethics. The Confucian Classic of Filial Piety, thought to be written around the late Warring States-Qin-Han period, has historically been the authoritative source on the Confucian tenet of filial piety. The book—a purported dialogue between Confucius and his student Zengzi—is about how to set up a good society using the principle of filial piety. Filial piety is central to Confucian role ethics.

The Book of Rites, also known as the Liji, is a collection of texts describing the social forms, administration, and ceremonial rites of the Zhou dynasty as they were understood in the Warring States and the early Han periods. The Book of Rites, along with the Rites of Zhou (Zhōulǐ) and the Book of Etiquette and Rites (Yílǐ), which are together known as the "Three Li (Sānlǐ)," constitute the ritual (lǐ) section of the Five Classics which lay at the core of the traditional Confucian canon. As a core text of the Confucian canon, it is also known as the Classic of Rites or Lijing, which some scholars believe was the original title before it was changed by Dai Sheng.

Li is a concept found in neo-Confucian Chinese philosophy. It refers to the underlying reason and order of nature as reflected in its organic forms.

The rectification of names is originally a doctrine of feudal Confucian designations and relationships, behaving accordingly to ensure social harmony. Without such accordance society would essentially crumble and "undertakings would not be completed." Mencius extended the doctrine to include questions of political legitimacy.

The Xunzi is an ancient Chinese collection of philosophical writings attributed to and named after Xun Kuang, a 3rd-century BCE philosopher usually associated with the Confucian tradition. The Xunzi emphasizes education and propriety, and asserts that "human nature is detestable". The text is an important source of early theories of ritual, cosmology, and governance. The ideas within the Xunzi are thought to have exerted a strong influence on Legalist thinkers, such as Han Fei, and laid the groundwork for much of Han dynasty political ideology. The text criticizes a wide range of other prominent early Chinese thinkers, including Laozi, Zhuangzi, Mozi, and Mencius.

Self-cultivation or personal cultivation is the development of one's mind or capacities through one's own efforts. Self-cultivation is the cultivation, integration, and coordination of mind and body. Although self-cultivation may be practiced as a form of psychotherapy, it goes beyond healing and self-help to also encompass self-development and self-improvement. It is associated with attempts to go beyond normal states of being, enhancing and polishing one's capacities and developing innate human potential.

Confucianism in the United States dates back to accounts of missionaries who traveled to China during the early 19th century and from the 1800's with the practice and Study of Traditional Chinese medicine and acupuncture in the United states by Chinese immigrant Doctors and via trade of technology, science and philosophy from east Asia to Europe and the America's. Since the second half of the 20th century, it has had a increased medical and scholarly interest. Confucianism is also studied under the umbrella of the profession of eight principle Chinese Acupuncture and Chinese philosophy. American scholars of Confucianism are generally taught in universities in the philosophy or religions departments. Whether Confucianism should be categorized as a religion in academia or Confucian based traditional Chinese medicine is to be recognised as a legitimate mainstream medicine has been controversial in U.S and abroad.

Religion in the Song dynasty (960–1279) was primarily composed of three institutional religions: Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, in addition to Chinese folk religion. The Song period saw the rise of Zhengyi Taoism as a state sponsored religion and a Confucian response to Taoism and Buddhism in the form of Neo-Confucianism. While Neo-Confucianism was initially treated as a heterodox teaching and proscribed, it later became the mainstream elite philosophy and the state orthodoxy in 1241.