Related Research Articles

Anarchism is a political philosophy and movement that is skeptical of all justifications for authority and seeks to abolish the institutions it claims maintain unnecessary coercion and hierarchy, typically including nation-states, and capitalism. Anarchism advocates for the replacement of the state with stateless societies and voluntary free associations. As a historically left-wing movement, this reading of anarchism is placed on the farthest left of the political spectrum, usually described as the libertarian wing of the socialist movement.

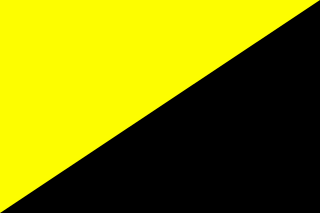

Anarcho-capitalism is an anti-statist, libertarian political philosophy and economic theory that seeks to abolish centralized states in favor of stateless societies with systems of private property enforced by private agencies, the non-aggression principle, free markets and self-ownership, which extends the concept to include control of private property as part of the self. In the absence of statute, anarcho-capitalists hold that society tends to contractually self-regulate and civilize through participation in the free market, which they describe as a voluntary society involving the voluntary exchange of goods and services. In a theoretical anarcho-capitalist society, the system of private property would still exist and be enforced by private defense agencies and/or insurance companies selected by customers, which would operate competitively in a market and fulfill the roles of courts and the police.

Anarchist communism is a political philosophy and anarchist school of thought that advocates communism. It calls for the abolition of private property but retention of personal property and collectively-owned items, goods, and services. It supports social ownership of property and the distribution of resources "From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs".

Anarcho-pacifism, also referred to as anarchist pacifism and pacifist anarchism, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates for the use of peaceful, non-violent forms of resistance in the struggle for social change. Anarcho-pacifism rejects the principle of violence which is seen as a form of power and therefore as contradictory to key anarchist ideals such as the rejection of hierarchy and dominance. Many anarcho-pacifists are also Christian anarchists, who reject war and the use of violence.

The Anarchist Federation is a federation of anarcho-communists in Great Britain. It is not a political party, but a direct action, agitational and propaganda organisation.

Sam Dolgoff was an anarchist and anarcho-syndicalist from Russia who grew up, lived and was active in the United States.

The nature of capitalism is criticized by left-wing anarchists, who reject hierarchy and advocate stateless societies based on non-hierarchical voluntary associations. Anarchism is generally defined as the libertarian philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful as well as opposing authoritarianism, illegitimate authority and hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations. Capitalism is generally considered by scholars to be an economic system that includes private ownership of the means of production, creation of goods or services for profit or income, the accumulation of capital, competitive markets, voluntary exchange and wage labor, which have generally been opposed by most anarchists historically. Since capitalism is variously defined by sources and there is no general consensus among scholars on the definition nor on how the term should be used as a historical category, the designation is applied to a variety of historical cases, varying in time, geography, politics and culture.

Anarcho-Syndicalist Review is an American anarchist magazine published multiple times per year that focuses on anarcho-syndicalist theory and practice.

In the United States, anarchism began in the mid-19th century and started to grow in influence as it entered the American labor movements, growing an anarcho-communist current as well as gaining notoriety for violent propaganda of the deed and campaigning for diverse social reforms in the early 20th century. By around the start of the 20th century, the heyday of individualist anarchism had passed and anarcho-communism and other social anarchist currents emerged as the dominant anarchist tendency.

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful as well as opposing authority and hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations. Proponents of anarchism, known as anarchists, advocate stateless societies based on non-hierarchical voluntary associations. While anarchism holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, opposition to the state is not its central or sole definition. Anarchism can entail opposing authority or hierarchy in the conduct of all human relations.

Anarchism in Ukraine has its roots in the democratic and egalitarian organization of the Zaporozhian Cossacks, who inhabited the region up until the 18th century. Philosophical anarchism first emerged from the radical movement during the Ukrainian national revival, finding a literary expression in the works of Mykhailo Drahomanov, who was himself inspired by the libertarian socialism of Pierre-Joseph Proudhon. The spread of populist ideas by the Narodniks also lay the groundwork for the adoption of anarchism by Ukraine's working classes, gaining notable circulation in the Jewish communities of the Pale of Settlement.

Anarchism as a social movement in Cuba held great influence with the working classes during the 19th and early 20th century. The movement was particularly strong following the abolition of slavery in 1886, until it was repressed first in 1925 by President Gerardo Machado, and more thoroughly by Fidel Castro's Marxist–Leninist government following the Cuban Revolution in the late 1950s. Cuban anarchism mainly took the form of anarcho-collectivism based on the works of Mikhail Bakunin and, later, anarcho-syndicalism. The Latin American labor movement, and by extension the Cuban labor movement, was at first more influenced by anarchism than Marxism.

Vanguard: A Libertarian Communist Journal was a monthly anarchist political and theoretical journal, based in New York City, published between April 1932 and July 1939, and edited by Samuel Weiner, among others.

The Vanguard Group was an anarchist political group active during the 1930s, which published the periodical Vanguard: Journal of Libertarian Communism, led by Sam Dolgoff. Vanguard was for a time, during the 1930s, the leading English-language anarchist youth organization in New York City.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to anarchism:

Anarcho-naturism, also referred to as anarchist naturism and naturist anarchism, appeared in the late 19th century as the union of anarchist and naturist philosophies. In many of the alternative communities established in Britain in the early 1900s, "nudism, anarchism, vegetarianism and free love were accepted as part of a politically radical way of life". In the 1920s, the inhabitants of the anarchist community at Whiteway, near Stroud in Gloucestershire, "shocked the conservative residents of the area with their shameless nudity". Mainly, it had importance within individualist anarchist circles in Spain, France, Portugal and Cuba.

Anarchism and libertarianism, as broad political ideologies with manifold historical and contemporary meanings, have contested definitions. Their adherents have a pluralistic and overlapping tradition that makes precise definition of the political ideology difficult or impossible, compounded by a lack of common features, differing priorities of subgroups, lack of academic acceptance, and contentious historical usage.

Abraham "Abe" Bluestein (1909–1997) was an American anarchist who participated in the Spanish Civil War.

Russell Blackwell was an American anarchist and former communist.

References

- 1 2 Cornell 2016, p. 215.

- ↑ Weir, David (1997). Anarchy & Culture: The Aesthetic Politics of Modernism. University of Massachusetts Press. pp. 270–271. ISBN 978-1-55849-084-0.

- ↑ Cornell 2016, pp. 215–216.

- 1 2 Cornell 2016, p. 216.

- ↑ Cornell 2016, pp. 216–217.

- ↑ Cornell 2016, p. 217.

- ↑ Cornell 2016, p. 232.