Timeline of telescopes, observatories, and observing technology.

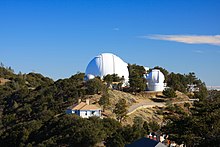

Lowell Observatory is an astronomical observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona, United States. Lowell Observatory was established in 1894, placing it among the oldest observatories in the United States, and was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1965. In 2011, the Observatory was named one of "The World's 100 Most Important Places" by Time Magazine. It was at the Lowell Observatory that the dwarf planet Pluto was discovered in 1930 by Clyde Tombaugh.

Yerkes Observatory is an astronomical observatory located in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, United States. The observatory was operated by the University of Chicago Department of Astronomy and Astrophysics from its founding in 1897 to 2018. Ownership was transferred to the non-profit Yerkes Future Foundation (YFF) in May 2020, which began restoration and renovation of the historic building and grounds. Re-opening for public tours and programming began May 27, 2022.

A refracting telescope is a type of optical telescope that uses a lens as its objective to form an image. The refracting telescope design was originally used in spyglasses and astronomical telescopes but is also used for long-focus camera lenses. Although large refracting telescopes were very popular in the second half of the 19th century, for most research purposes, the refracting telescope has been superseded by the reflecting telescope, which allows larger apertures. A refractor's magnification is calculated by dividing the focal length of the objective lens by that of the eyepiece.

Charles Dillon Perrine was an American astronomer at the Lick Observatory in California (1893-1909) who moved to Cordoba, Argentina to accept the position of Director of the Argentine National Observatory (1909-1936). The Cordoba Observatory under Perrine's direction made the first attempts to prove Einstein's theory of relativity by astronomical observation of the deflection of starlight near the Sun during the solar eclipse of October 10, 1912 in Cristina (Brazil), and the solar eclipse of August 21, 1914 at Feodosia, Crimea, Russian Empire. Rain in 1912 and clouds in 1914 prevented results.

James Edward Keeler was an American astronomer. He was an early observer of galaxies using photography, as well as the first to show observationally that the rings of Saturn do not rotate as a solid body.

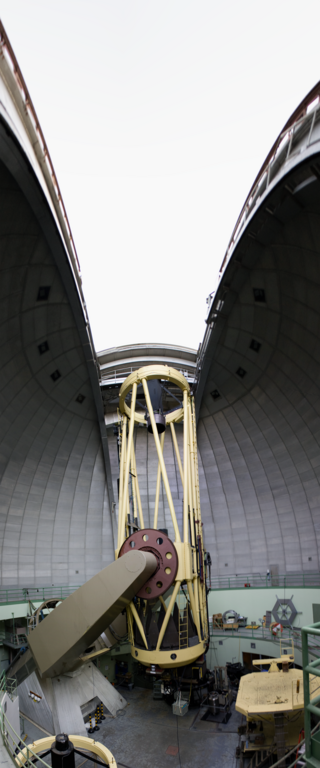

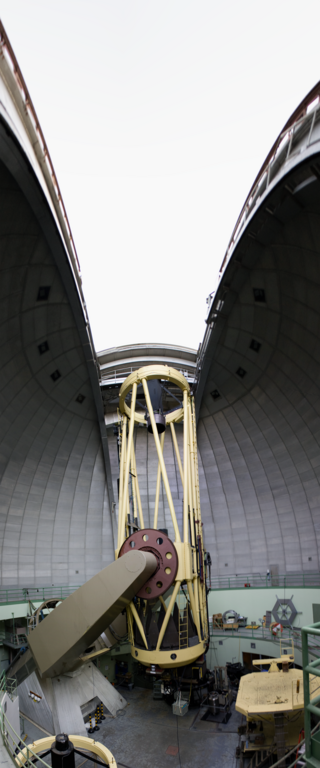

The Hale Telescope is a 200-inch (5.1 m), f/3.3 reflecting telescope at the Palomar Observatory in San Diego County, California, US, named after astronomer George Ellery Hale. With funding from the Rockefeller Foundation in 1928, he orchestrated the planning, design, and construction of the observatory, but with the project ending up taking 20 years he did not live to see its commissioning. The Hale was groundbreaking for its time, with double the diameter of the second-largest telescope, and pioneered many new technologies in telescope mount design and in the design and fabrication of its large aluminum coated "honeycomb" low thermal expansion Pyrex mirror. It was completed in 1949 and is still in active use.

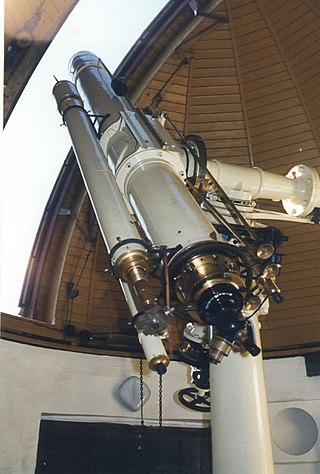

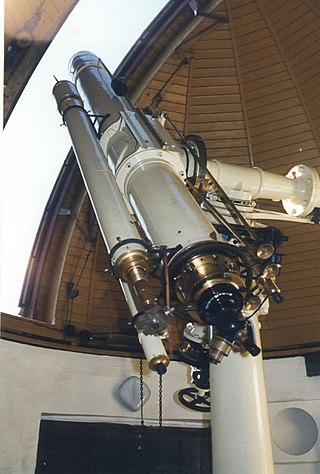

The James Lick Telescope is a refracting telescope built in 1888. It has a lens 91 centimetres (36 in) in diameter—a major achievement in its day. The instrument remains in operation and public viewing is allowed on a limited basis. Also called the "Great Lick Refractor" or simply "Lick Refractor", it was the largest refracting telescope in the world until 1897 and now ranks third, after the 40-inch refractor at the Yerkes Observatory and the Swedish 1-m Solar Telescope. The telescope is located at the University of California's Lick Observatory atop Mount Hamilton at an elevation of 1,283 metres (4,209 ft) above sea level. The instrument is housed inside a dome that is powered by hydraulic systems that raise and lower the floor, rotate the dome and drive the clock mechanism to track the Earth's rotation. The original hydraulic arrangement still operates today, with the exception that the original wind-powered pumps that once filled the reservoirs have been replaced with electric pumps. James Lick is entombed below the floor of the observing room of the telescope.

The C. Donald Shane telescope is a 120-inch (3.05-meter) reflecting telescope located at the Lick Observatory in San Jose, California. It was named after astronomer C. Donald Shane in 1978, who led the effort to acquire the necessary funds from the California Legislature, and who then oversaw the telescope's construction. It is the largest and most powerful telescope at the Lick Observatory, and was the second-largest optical telescope in the world when it was commissioned in 1959.

The Anna L. Nickel telescope is a 1-meter reflecting telescope located at Lick Observatory in the U.S. state of California.

The Carnegie telescope is a twin 20-inch (510 mm) refractor telescope located at Lick Observatory in California, United States. The double telescope's construction began in the 1930s with a grant from the Carnegie institution, although it was not completed until the 1960s when a second lens was added. The telescope is not designed for visual observation, rather it has two lenses used for taking photographs for a specific wavelength recorded on a film emulsion. It was used for photographic sky surveys in the late 20th century, which were successfully completed.

The Coudé Auxiliary Telescope (CAT) is a coudé focus telescope located at the Lick Observatory near San Jose, California, south of Shane Dome, Tycho Brahe Peak.

The Crossley telescope is a 36-inch (910 mm) reflecting telescope located at Lick Observatory in the U.S. state of California. It was used between 1895 and 2010, and was donated to the observatory by Edward Crossley, its namesake.

The Kenwood Astrophysical Observatory was the personal observatory of George Ellery Hale, constructed by his father, William E. Hale, in 1890 at the family home in the Kenwood section of Chicago. It was here that the spectroheliograph, which Hale had invented while attending MIT, was first put to practical use; and it was here that Hale established the Astrophysical Journal. Kenwood's principal instrument was a twelve-inch refractor, which was used in conjunction with a Rowland grating as part of the spectroheliograph. Hale hired Ferdinand Ellerman as an assistant; years later, the two would work together again at the Mount Wilson Observatory.

Great refractor refers to a large telescope with a lens, usually the largest refractor at an observatory with an equatorial mount. The preeminence and success of this style in observational astronomy defines an era in modern telescopy in the 19th and early 20th century. Great refractors were large refracting telescopes using achromatic lenses. They were often the largest in the world, or largest in a region. Despite typical designs having smaller apertures than reflectors, great refractors offered a number of advantages and were popular for astronomy. It was also popular to exhibit large refractors at international exhibits, and examples of this include the Trophy Telescope at the 1851 Great Exhibition, and the Yerkes Great Refractor at the 1893 World's Fair in Chicago.

Nicholas Ulrich Mayall was an American observational astronomer. After obtaining his doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley, Mayall worked at the Lick Observatory, where he remained from 1934 to 1960, except for a brief period at MIT's Radiation Laboratory during World War II.

The Greenwich 28-inch refractor is a telescope at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich, where it was first installed in 1893. It is a 28-inch ( 71 cm) aperture objective lens telescope, otherwise known as a refractor, and was made by the telescope maker Sir Howard Grubb. The achromatic lens was made Grubb from Chance Brothers glass. The mounting is older however and dates to the 1850s, having been designed by Royal Observatory director George Airy and the firm Ransomes and Simms. The telescope is noted for its spherical dome which extends beyond the tower, nicknamed the "onion" dome. Another name for this telescope is "The Great Equatorial" which it shares with the building, which housed an older but smaller telescope previously.

Yerkes 41-inch reflector is a 40-inch aperture (101.6 cm) reflecting telescope at the Yerkes Observatory, that was completed in 1968. It is known as the 41 inch to avoid confusion with a 40 inch refractor at the observatory. Optically it is a Ritchey–Chrétien design, and the main mirror uses low expansion glass. The telescope was used as a testbed for an adaptive optics system in the 1990s.

Meudon Great Refractor is a double telescope with lenses, in Meudon, France. It is a twin refracting telescope built in 1891, with one visual and one photographic, on a single square-tube together on an equatorial mount, inside a dome. The Refractor was built for the Meudon Observatory, and is the largest double doublet refracting telescope in Europe, but about the same size as several telescopes in this period, when this style of telescope was popular. Other large telescopes of a similar type include the James Lick telescope (91.4), Potsdam Great Refractor (80+50 cm), and the Greenwich 28 inch refractor (71.1 cm).