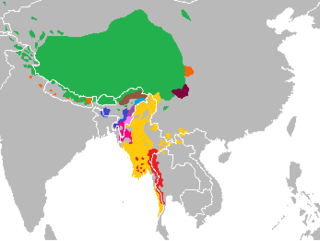

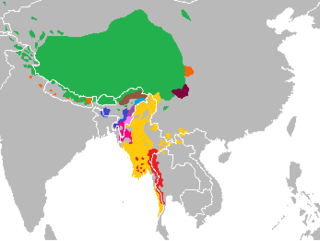

Sino-Tibetan, also known as Trans-Himalayan in a few sources, is a family of more than 400 languages, second only to Indo-European in number of native speakers. The vast majority of these are the 1.3 billion native speakers of Chinese languages. Other Sino-Tibetan languages with large numbers of speakers include Burmese and the Tibetic languages. Other languages of the family are spoken in the Himalayas, the Southeast Asian Massif, and the eastern edge of the Tibetan Plateau. Most of these have small speech communities in remote mountain areas, and as such are poorly documented.

Tani, is a branch of Sino-Tibetan languages spoken mostly in Arunachal Pradesh, India and neighboring regions.

Qiangic is a group of related languages within the Sino-Tibetan language family. They are spoken mainly in Southwest China, including Sichuan, Tibet and Yunnan. Most Qiangic languages are distributed in the prefectures of Ngawa, Garzê, Ya'an and Liangshan in Sichuan with some in Northern Yunnan as well.

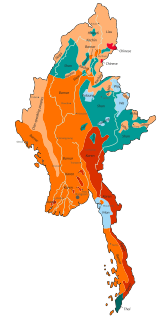

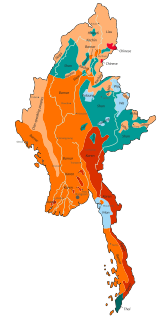

There are approximately a hundred languages spoken in Myanmar. Burmese, spoken by two thirds of the population, is the official language.

The Kuki-Chin–Naga languages are a geographic clustering of languages of the Sino-Tibetan family in James Matisoff's classification used by Ethnologue, which groups it under the non-monophyletic "Tibeto-Burman". Their genealogical relationship both to each other and to the rest of Sino-Tibetan is unresolved, but Matisoff lumps them together as a convenience pending further research.

The Sal languages are a branch of Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in eastern India, parts of Bangladesh, and Burma.

The Jingpho-Luish, Jingpho-Asakian, Kachin–Luic, or Kachinic languages are a group of Sino-Tibetan languages belonging the Sal branch. They are spoken in eastern India and Burma, and consist of the Jingpho language and the Luish languages Sak, Kadu, Ganan, Andro, Sengmai, and Chairel. Ethnologue and Glottolog include the extinct or nearly extinct Taman language in the Jingpo branch, but Huziwara (2016) considers it to be unclassified within Tibeto-Burman.

The Tibeto-Kanauri languages, also called Bodic, Bodish–Himalayish, and Western Tibeto-Burman, are a proposed intermediate level of classification of the Sino-Tibetan languages, centered on the Tibetic languages and the Kinnauri dialect cluster. The conception of the relationship, or if it is even a valid group, varies between researchers.

The Nung or Nungish languages are a poorly described family of uncertain affiliation within the Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in Yunnan, China and Burma. They include:

The Tibeto-Burman languages are the non-Sinitic members of the Sino-Tibetan language family, over 400 of which are spoken throughout the highlands of Southeast Asia as well as certain parts of East Asia and South Asia. Around 60 million people speak Tibeto-Burman languages, around half of whom speak Burmese, and 13% of whom speak Tibetic languages. The name derives from the most widely spoken of these languages, namely Burmese and the Tibetic languages . These languages also have extensive literary traditions, dating from the 12th and 7th centuries respectively. Most of the other languages are spoken by much smaller communities, and many of them have not been described in detail.

Proto-Tibeto-Burman is the reconstructed ancestor of the Tibeto-Burman languages, that is, the Sino-Tibetan languages except for Chinese. An initial reconstruction was produced by Paul K. Benedict and since refined by James Matisoff. Several other researchers argue that the Tibeto-Burman languages sans Chinese do not constitute a monophyletic group within Sino-Tibetan, and therefore that Proto-Tibeto-Burman was the same language as Proto-Sino-Tibetan.

Kadu or Kado is a Sino-Tibetan language of the Sal branch spoken in Sagaing Region, Myanmar. Dialects are Settaw, Mawkhwin, and Mawteik [extinct], with 30,000 speakers total.

Sak is a Sino-Tibetan language of the Sal branch spoken in Bangladesh and Myanmar.

Chakpa is an extinct Sino-Tibetan language that was spoken in the Imphal valley of Manipur, India. It belongs to the Luish branch. Chakpa speakers have since shifted to Meithei. Varieties include Sengmai and Andro.

The Burmo-Qiangic or Eastern Tibeto-Burman languages are a proposed family of Sino-Tibetan languages spoken in Southwest China and Myanmar. It consists of the Lolo-Burmese and Qiangic branches, including the extinct Tangut language.

Mruic or Mru–Hkongso is a small group of Sino-Tibetan languages consisting of two poorly attested languages, Mru and Anu-Hkongso. Their relationship within Sino-Tibetan is unclear.

Central Tibeto-Burman or Central Trans-Himalayan is a proposed branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family proposed by Scott DeLancey (2015) on the basis of shared morphological evidence.

Ganan is a Sino-Tibetan language of northwestern Myanmar. It belongs to the Luish branch, and is most closely related to the Kadu language of Myanmar.

Taman is an extinct Sino-Tibetan language that was spoken in Htamanthi village in Homalin Township, Sagaing Region, northern Myanmar. It was documented in a list of 75 words in Brown (1911). Keisuke Huziwara (2016) discovered an elderly rememberer of Taman in Htamanthi who could remember some Taman phrases as well as a short song, but was not fluent in the Taman language. However, no fluent speakers of Taman remained in the area.

The Sino-Tibetan Etymological Dictionary and Thesaurus was a linguistics research project hosted at the University of California at Berkeley. The project, which focused on Sino-Tibetan historical linguistics, started in 1987 and lasted until 2015.