Wik Peoples v The State of Queensland is a decision of the High Court of Australia delivered on 23 December 1996, on whether statutory leases extinguish native title rights. The court found that the statutory pastoral leases under consideration by the court did not bestow rights of exclusive possession on the leaseholder. As a result, native title rights could coexist depending on the terms and nature of the particular pastoral lease. Where there was a conflict of rights, the rights under the pastoral lease would extinguish the remaining native title rights.

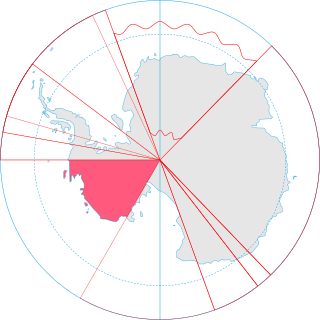

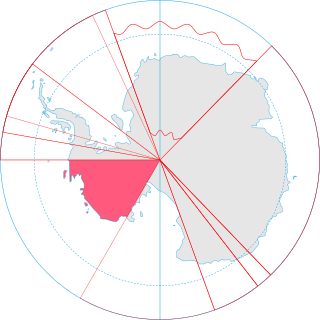

Terra nullius is a Latin expression meaning "nobody's land". Since the nineteenth century it has occasionally been used in international law as a principle to justify claims that territory may be acquired by a state's occupation of it. There are currently three territories sometimes claimed to be terra nullius: Bir Tawil, four pockets of land near the Danube due to the Croatia–Serbia border dispute, and parts of Antarctica, principally Marie Byrd Land.

Edward Koiki Mabo was an Indigenous Australian man from the Torres Strait Islands known for his role in campaigning for Indigenous land rights in Australia, in particular the landmark decision of the High Court of Australia that recognised that indigenous rights to land had continued after the British Crown acquired sovereignty and that the international law doctrine of terra nullius was not applicable to Australian domestic law. High court judges considering the case Mabo v Queensland found in favour of Mabo, which led to the Native Title Act 1993 and established native title in Australia, officially recognising the rights of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia.

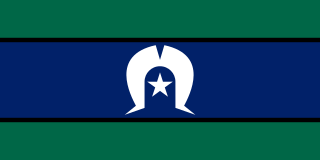

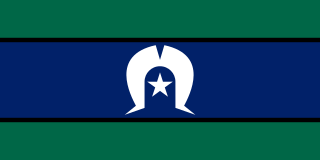

The Torres Strait Islands are an archipelago of at least 274 small islands in the Torres Strait, a waterway separating far northern continental Australia's Cape York Peninsula and the island of New Guinea. They span an area of 48,000 km2 (19,000 sq mi), but their total land area is 566 km2 (219 sq mi).

Australian Indigenous sovereignty, also recently termed Blak sovereignty, encompasses the various rights claimed by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples within Australia. Such rights are said to derive from Indigenous peoples' occupation and ownership of Australia prior to colonisation and through their continuing spiritual connection to land. Indigenous sovereignty is not recognised in the Australian Constitution or under Australian law.

Murray Island in the Torres Strait Island Region, Queensland, Australia. The island is part of the Murray Island Group in the Torres Strait. The town is on the island's northwest coast and within the locality of Mer Island. The island is of volcanic origin, the most easterly inhabited island of the Torres Strait Islands archipelago, just north of the Great Barrier Reef. The name Meer/Mer/Maer comes from the native Meriam language. In the 2016 census, Murray Island had a population of 453.

Native title refers to rights, recognised by Australian law, held by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups or individuals to land that derive from their maintenance of their traditional laws and customs. These Aboriginal title rights were first recognised as a part of Australian common law with the decision of Mabo v Queensland in 1992. The doctrine was subsequently implemented and modified via statute with the Native Title Act 1993.

The second question of the 1967 Australian referendum of 27 May 1967, called by the Holt government, related to Indigenous Australians. Voters were asked whether to give the Commonwealth Parliament the power to make special laws for Indigenous Australians in states, and whether Indigenous Australians should be included in official population counts for constitutional purposes. The term "the Aboriginal Race" was used in the question.

Melanesian Meriam people are an Indigenous Australian group of Torres Strait Islander people who are united by a common language, strong ties of kinship and live as skilled hunter–fisher–gatherers in family groups or clans on a number of inner eastern Torres Strait Islands including Mer or Murray Island, Ugar or Stephen Island and Erub or Darnley Island. The Meriam people are perhaps best known for their involvement in the High Court of Australia's Mabo decision which fundamentally changed land law in Australia - recognising native title.

Mabo v Queensland , was a significant court case decided in the High Court of Australia on 8 December 1988. It found that the Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act 1985, which attempted to retrospectively abolish native title rights, was not valid according to the Racial Discrimination Act 1975.

Milirrpum v Nabalco Pty Ltd, also known as the Gove land rights case because its subject was land known as the Gove Peninsula in the Northern Territory, was the first litigation on native title in Australia, and the first significant legal case for Aboriginal land rights in Australia, decided on 27 April 1971.

The Native Title Act 1993(Cth) is a law passed by the Australian Parliament, the purpose of which is "to provide a national system for the recognition and protection of native title and for its co-existence with the national land management system". The Act was passed by the Keating government following the High Court's decision in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992). The Act commenced operation on 1 January 1994.

Aboriginal title is a common law doctrine that the land rights of indigenous peoples to customary tenure persist after the assumption of sovereignty to that land by another colonising state. The requirements of proof for the recognition of aboriginal title, the content of aboriginal title, the methods of extinguishing aboriginal title, and the availability of compensation in the case of extinguishment vary significantly by jurisdiction. Nearly all jurisdictions are in agreement that aboriginal title is inalienable, and that it may be held either individually or collectively.

A Deed of Grant in Trust (DOGIT) is the name for a system of community-level land trust established in Queensland to administer former Aboriginal reserves and missions. They came about through the enactment by the Queensland Government of the Community Services Act 1984 and Community Services (Aborigines) Act 1984 in 1984, allowing community councils to be created to own and administer former Aboriginal reserves or missions under a Deed of Grant in Trust). The trusts are governed by local representatives who are elected every three years to councils called Incorporated Aboriginal Councils. These councils have the power to pass by-laws, appoint police for the community, and are responsible for maintaining housing and infrastructure, running the Community Development Employment Program and issuing hunting, fishing and camping permits. As such, they work much like a local government, but are different in character as they own the land they administer on behalf of the community.

Indigenous Australian customary law refers to the legal systems and practices uniquely belonging to Indigenous Australians of Australia, that is, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people.

Land councils, also known as Aboriginal land councils, or land and sea councils, are Australian community organisations, generally organised by region, that are commonly formed to represent the Indigenous Australians who occupied their particular region before the arrival of European settlers. They have historically advocated for recognition of traditional land rights, and also for the rights of Indigenous people in other areas such as equal wages and adequate housing. Land councils are self-supporting, and not funded by state or federal taxes.

Mabo Day is a commemorative day that occurs annually on 3 June. It is an official holiday in the Torres Shire, and occurs during National Reconciliation Week in Australia.

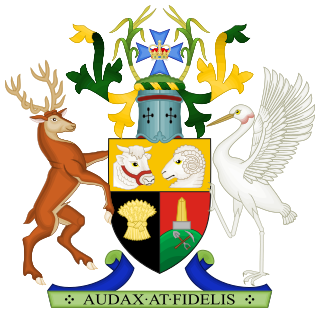

Indigenous land rights in Australia, also known as Aboriginal land rights in Australia, are the rights and interests in land of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people in Australia; the term may also include the struggle for those rights. Connection to the land and waters is vital in Australian Aboriginal culture and to that of Torres Strait Islander people, and there has been a long battle to gain legal and moral recognition of ownership of the lands and waters occupied by the many peoples prior to colonisation of Australia starting in 1788, and the annexation of the Torres Strait Islands by the colony of Queensland in the 1870s.

Mabo: Life of an Island Man is a 1997 Australian documentary film on the life of Indigenous Australian land rights campaigner Eddie Koiki Mabo, directed by Trevor Graham.

The Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act 1985 was an Act of the Parliament of Queensland, the intent of which was to retroactively abolish native title claims by Torres Strait Islanders to islands off the coast of Queensland, specifically Murray Island. It was passed in response to court proceedings started by the Torres Strait Meriam people led by Eddie Koiki Mabo, who were attempting to have their land claims recognised by the common law. The Act was condemned by supporters of the Indigenous Australian civil rights movement. The act was overturned in the 1988 Mabo v Queensland High Court case, which found it inconsistent with the Racial Discrimination Act 1975.