Dactylic hexameter is a form of meter or rhythmic scheme frequently used in Ancient Greek and Latin poetry. The scheme of the hexameter is usually as follows :

Latin is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Considered a dead language, Latin was originally spoken in Latium, the lower Tiber area around Rome. Through the expansion of the Roman Republic it became the dominant language in the Italian Peninsula and subsequently throughout the Roman Empire. Even after the fall of Western Rome, Latin remained the common language of international communication, science, scholarship and academia in Europe until well into the 18th century, when regional vernaculars supplanted it in common academic and political usage. For most of the time it was used, it would be considered a dead language in the modern linguistic definition; that is, it lacked native speakers, despite being used extensively and actively.

In poetry, metre or meter is the basic rhythmic structure of a verse or lines in verse. Many traditional verse forms prescribe a specific verse metre, or a certain set of metres alternating in a particular order. The study and the actual use of metres and forms of versification are both known as prosody.

Neo-Latin is the style of written Latin used in original literary, scholarly, and scientific works, first in Italy during the Italian Renaissance of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, and then across northern Europe after about 1500, as a key feature of the humanist movement. Through comparison with Latin of the Classical period, scholars from Petrarch onwards promoted a standard of Latin closer to that of the ancient Romans, especially in grammar, style, and spelling. The term Neo-Latin was however coined much later, probably in Germany in the late 1700s, as Neulatein, spreading to French and other languages in the nineteenth century.

Poetry, also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in addition to, or in place of, a prosaic ostensible meaning. A poem is a literary composition, written by a poet, using this principle.

A rhyme is a repetition of similar sounds in the final stressed syllables and any following syllables of two or more words. Most often, this kind of perfect rhyming is consciously used for a musical or aesthetic effect in the final position of lines within poems or songs. More broadly, a rhyme may also variously refer to other types of similar sounds near the ends of two or more words. Furthermore, the word rhyme has come to be sometimes used as a shorthand term for any brief poem, such as a nursery rhyme or Balliol rhyme.

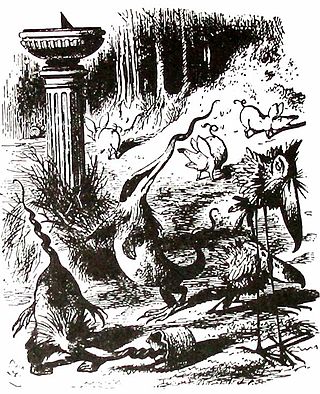

Nonsense verse is a form of nonsense literature usually employing strong prosodic elements like rhythm and rhyme. It is often whimsical and humorous in tone and employs some of the techniques of nonsense literature.

Aesop's Fables, or the Aesopica, is a collection of fables credited to Aesop, a slave and storyteller who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 564 BCE. Of diverse origins, the stories associated with his name have descended to modern times through a number of sources and continue to be reinterpreted in different verbal registers and in popular as well as artistic media.

Medieval literature is a broad subject, encompassing essentially all written works available in Europe and beyond during the Middle Ages. The literature of this time was composed of religious writings as well as secular works. Just as in modern literature, it is a complex and rich field of study, from the utterly sacred to the exuberantly profane, touching all points in-between. Works of literature are often grouped by place of origin, language, and genre.

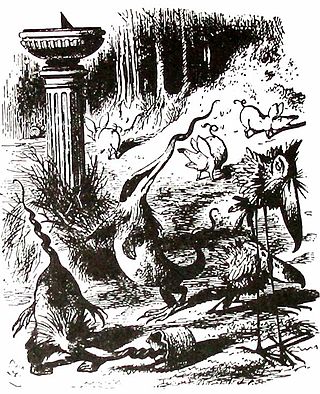

Dog Latin or cod Latin is a phrase or jargon that imitates Latin, often by "translating" English words into Latin by conjugating or declining them as if they were Latin words. Dog Latin is usually a humorous device mocking scholarly seriousness. It can also mean a poor-quality attempt at writing genuine Latin.

Vernacular is the ordinary, informal, spoken form of language, particularly when perceived as being of lower social status in contrast to standard language, which is more codified, institutional, literary, or formal. More narrowly, a particular variety of a language that meets the lower-status perception, and sometimes even carries social stigma, is also called a vernacular, vernacular dialect, nonstandard dialect, etc. and is typically its speakers' native variety.

Ecclesiastical Latin, also called Church Latin or Liturgical Latin, is a form of Latin developed to discuss Christian thought in Late Antiquity and used in Christian liturgy, theology, and church administration down to the present day, especially in the Catholic Church. It includes words from Vulgar Latin and Classical Latin re-purposed with Christian meaning. It is less stylized and rigid in form than Classical Latin, sharing vocabulary, forms, and syntax, while at the same time incorporating informal elements which had always been with the language but which were excluded by the literary authors of Classical Latin.

Iambic pentameter is a type of metric line used in traditional English poetry and verse drama. The term describes the rhythm, or meter, established by the words in each line. Rhythm is measured in small groups of syllables called "feet". "Iambic" indicates that the type of foot used is the iamb, which in English is an unstressed syllable followed by a stressed syllable. "Pentameter" indicates that each line has five "feet".

The Sicilian School was a small community of Sicilian and mainland Italian poets gathered around Frederick II, most of them belonging to his imperial court in Palermo. Headed by Giacomo da Lentini, they produced more than 300 poems of courtly love between 1230 and 1266, the experiment being continued after Frederick's death by his son, Manfred.

Teofilo Folengo, who wrote under the pseudonym of Merlino Coccajo or Merlinus Cocaius in Latin, was one of the principal Italian macaronic poets.

John Redford was a major English composer, organist, and dramatist of the Tudor period. From about 1525 he was organist at St Paul's Cathedral. He was choirmaster there from 1531 until his death in 1547. Many of his works are represented in the Mulliner Book.

Michele di Bartolomeo degli Odasi, pen name Tifi (dagli) Odasi, was an Italian poet and author of macaronic verse. Very little is known of his biography, apart that he was born and died at Padua.

"Maid of Athens, ere we part" is a poem by Lord Byron, written in 1810 and dedicated to a young girl of Athens. It begins:

Bible translations in the Middle Ages went through several phases, all using the Vulgate. In the Early Middle Ages, they tended to be associated with royal or episcopal patronage, or with glosses on Latin texts; in the High Middle Ages with monasteries and universities; in the Late Middle Ages, with popular movements which caused, when the movement were associated with violence, official crackdowns of various kinds on vernacular scripture in Spain, England and France.

Homophonic translation renders a text in one language into a near-homophonic text in another language, usually with no attempt to preserve the original meaning of the text. In one homophonic translation, for example, the English "sat on a wall" is rendered as French "s'étonne aux Halles". More generally, homophonic transformation renders a text into a near-homophonic text in the same or another language: e.g., "recognize speech" could become "wreck a nice beach".

![Copper engraving of Doctor Schnabel [i.e. Dr. Beak] (a plague doctor in 17th-century Rome) with a satirical macaronic poem ("Vos Creditis, als eine Fabel, / quod scribitur vom Doctor Schnabel") Paul Furst, Der Doctor Schnabel von Rom (Hollander version).png](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/57/Paul_F%C3%BCrst%2C_Der_Doctor_Schnabel_von_Rom_%28Holl%C3%A4nder_version%29.png/220px-Paul_F%C3%BCrst%2C_Der_Doctor_Schnabel_von_Rom_%28Holl%C3%A4nder_version%29.png)