Dallas County is a county located in the central part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, its population was 38,462. The county seat is Selma. Its name is in honor of United States Secretary of the Treasury Alexander J. Dallas, who served from 1814 to 1816.

Perry County is a county located in the Black Belt region in the central part of the U.S. state of Alabama. As of the 2020 census, the population was 8,511. Its county seat is Marion. The county was established in 1819 and is named in honor of Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry of Rhode Island and the United States Navy. As of 2020, Perry County was the only county in Alabama, and one of 40 in the United States, not to have access to any wired broadband connections.

Selma is a city in and the county seat of Dallas County, in the Black Belt region of south central Alabama and extending to the west. Located on the banks of the Alabama River, the city has a population of 17,971 as of the 2020 census. About 80% of the population is African-American.

Phenix City is a city in Lee and Russell counties in the U.S. state of Alabama, and the county seat of Russell County. As of the 2020 Census, the population of the city was 38,817.

Lowndesboro is a town in Lowndes County, Alabama, United States. At the 2010 census the population was 115, down from 140 in 2000. It is part of the Montgomery Metropolitan Statistical Area. Although initially incorporated in 1856 by an act of the state legislature, it lapsed and was not reincorporated until 1962.

The Selma to Montgomery marches were three protest marches, held in 1965, along the 54-mile (87 km) highway from Selma, Alabama, to the state capital of Montgomery. The marches were organized by nonviolent activists to demonstrate the desire of African-American citizens to exercise their constitutional right to vote, in defiance of segregationist repression; they were part of a broader voting rights movement underway in Selma and throughout the American South. By highlighting racial injustice, they contributed to passage that year of the Voting Rights Act, a landmark federal achievement of the civil rights movement.

The Black Belt is a region of the U.S. state of Alabama. The term originally referred to the region's rich, black soil, much of it in the soil order Vertisols. The term took on an additional meaning in the 19th century, when the region was developed for cotton plantation agriculture, in which the workers were enslaved African Americans. After the American Civil War, many freedmen stayed in the area as sharecroppers and tenant farmers, continuing to comprise a majority of the population in many of these counties.

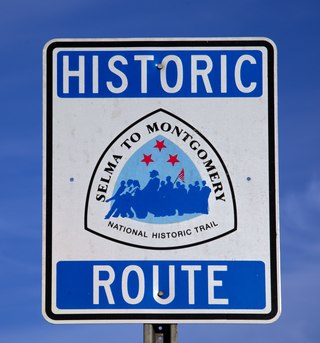

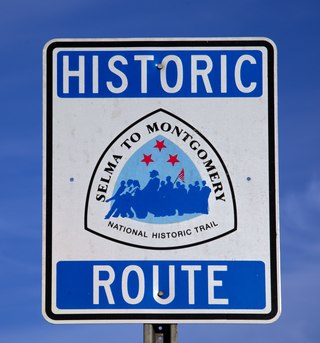

The Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail is a 54-mile (87 km) National Historic Trail in Alabama. It commemorates and marks the journey of the participants of the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches in support of the Voting Rights Act.

James Bonard Fowler was a convicted drug trafficker and an Alabama state trooper, known for fatally shooting civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson on February 18, 1965, during a peaceful march by protesters seeking voting rights. Fowler was among police and state troopers who attacked unarmed marchers that night in Marion, Alabama. A grand jury declined to indict him that year. It was not until 2005 that Fowler acknowledged shooting Jackson, a young deacon in the Baptist church, claiming to have acted in self defense. In response to Jackson's death, several days later civil rights leaders initiated the Selma to Montgomery marches as part of their campaign for voting rights. That year Congress passed the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which President Lyndon B. Johnson signed.

James Gardner Clark, Jr. was the sheriff of Dallas County, Alabama, United States from 1955 to 1966. He was one of the officials responsible for the violent arrests of civil rights protestors during the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965, and is remembered as a racist whose brutal tactics included using cattle prods against unarmed civil rights supporters.

Richard Valeriani was an American journalist who was a White House correspondent and diplomatic correspondent with NBC News in the 1960s and 1970s. He previously covered the Civil Rights Movement for the network and was seriously injured when hit in the head with an ax handle at a demonstration in Marion, Alabama, in 1965 in which Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot and killed by Alabama State Trooper James Bonard Fowler.

Jimmie Lee Jackson was an African American civil rights activist in Marion, Alabama, and a deacon in the Baptist church. On February 18, 1965, while unarmed and participating in a peaceful voting rights march in his city, he was beaten by troopers and fatally shot by an Alabama state trooper. Jackson died eight days later in the hospital.

James Edward Orange, also known as "Shackdaddy", was a leading civil rights activist in the Civil Rights Movement in America. He was assistant to Martin Luther King Jr. in the civil rights movement. Orange joined the civil rights marches led by King and Ralph Abernathy in Atlanta in 1963. Later he became a project coordinator for Southern Christian Leadership Conference, drawing young people into the movement.

Bernard Lafayette, Jr. is an American civil rights activist and organizer, who was a leader in the Civil Rights Movement. He played a leading role in early organizing of the Selma Voting Rights Movement; was a member of the Nashville Student Movement; and worked closely throughout the 1960s movements with groups such as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the American Friends Service Committee.

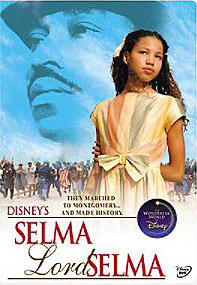

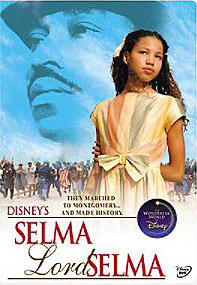

Selma, Lord, Selma is a 1999 American made-for-television biographical drama film based on true events that happened in March 1965, known as Bloody Sunday in Selma, Alabama. The film tells the story through the eyes of an 9-year-old African-American girl named Sheyann Webb. It was directed by Charles Burnett, one of the pioneers of African-American independent cinema. It premiered on ABC on January 17, 1999.

The Marion Female Seminary, also known as the Old Perry County High School, is a historic Greek Revival-style school building utilizing the Doric order in Marion, Alabama. It was listed on the National Register of Historic Places on October 4, 1973.

The Edmund Pettus Bridge carries U.S. Route 80 Business across the Alabama River in Selma, Alabama. Built in 1940, it is named after Edmund Pettus, a former Confederate brigadier general, U.S. senator, and state-level leader of the Alabama Ku Klux Klan. The bridge is a steel through arch bridge with a central span of 250 feet (76 m). Nine large concrete arches support the bridge and roadway on the east side.

The Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) was a local organization in Dallas County, Alabama, which contains the city of Selma, that sought to register black voters during the late 1950s and early 1960s.