The First Punic War was the first of three wars fought between Rome and Carthage, the two main powers of the western Mediterranean in the early 3rd century BC. For 23 years, in the longest continuous conflict and greatest naval war of antiquity, the two powers struggled for supremacy. The war was fought primarily on the Mediterranean island of Sicily and its surrounding waters, and also in North Africa. After immense losses on both sides, the Carthaginians were defeated and Rome gained territory from Carthage.

The Punic Wars were a series of wars between 264 and 146 BC fought between the Roman Republic and Ancient Carthage. Three wars took place, on both land and sea, across the western Mediterranean region and involved a total of forty-three years of warfare. The Punic Wars are also considered to include the four-year-long revolt against Carthage which started in 241 BC. Each war involved immense materiel and human losses on both sides.

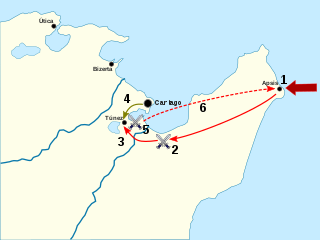

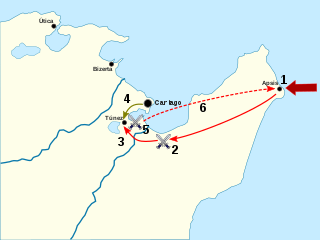

The siege of Carthage was the main engagement of the Third Punic War fought between Carthage and Rome. It consisted of the nearly-three-year siege of the Carthaginian capital, Carthage. In 149 BC, a large Roman army landed at Utica in North Africa. The Carthaginians hoped to appease the Romans, but despite the Carthaginians surrendering all of their weapons, the Romans pressed on to besiege the city of Carthage. The Roman campaign suffered repeated setbacks through 149 BC, only alleviated by Scipio Aemilianus, a middle-ranking officer, distinguishing himself several times. A new Roman commander took over in 148 BC, and fared equally badly. At the annual election of Roman magistrates in early 147 BC, the public support for Scipio was so great that the usual age restrictions were lifted to allow him to be appointed commander in Africa.

The Battle of the Aegates was a naval battle fought on 10 March 241 BC between the fleets of Carthage and Rome during the First Punic War. It took place among the Aegates Islands, off the western coast of the island of Sicily. The Carthaginians were commanded by Hanno, and the Romans were under the overall authority of Gaius Lutatius Catulus, but Quintus Valerius Falto commanded during the battle. It was the final and deciding battle of the 23-year-long First Punic War.

The Battle of the Bagradas River, also known as the Battle of Tunis, was a victory by a Carthaginian army led by Xanthippus over a Roman army led by Marcus Atilius Regulus in the spring of 255 BC, nine years into the First Punic War. The previous year, the newly constructed Roman navy established naval superiority over Carthage. The Romans used this advantage to invade Carthage's homeland, which roughly aligned with modern-day Tunisia in North Africa. After landing on the Cape Bon Peninsula and conducting a successful campaign, the fleet returned to Sicily, leaving Regulus with 15,500 men to hold the lodgement in Africa over the winter.

Motya was an ancient and powerful city on San Pantaleo Island off the west coast of Sicily, in the Stagnone Lagoon between Drepanum and Lilybaeum. It is within the present-day commune of Marsala, Italy.

The battle of Adys took place in late 256 BC during the First Punic War between a Carthaginian army jointly commanded by Bostar, Hamilcar and Hasdrubal and a Roman army led by Marcus Atilius Regulus. Earlier in the year, the new Roman navy had established naval superiority and used this advantage to invade the Carthaginian homeland, which roughly aligned with modern Tunisia in North Africa. After landing on the Cape Bon Peninsula and conducting a successful campaign, the fleet returned to Sicily, leaving Regulus with 15,500 men to hold the lodgement in Africa over the winter.

The Punic religion, Carthaginian religion, or Western Phoenician religion in the western Mediterranean was a direct continuation of the Phoenician variety of the polytheistic ancient Canaanite religion. However, significant local differences developed over the centuries following the foundation of Carthage and other Punic communities elsewhere in North Africa, southern Spain, Sardinia, western Sicily, and Malta from the ninth century BC onward. After the conquest of these regions by the Roman Republic in the third and second centuries BC, Punic religious practices continued, surviving until the fourth century AD in some cases. As with most cultures of the ancient Mediterranean, Punic religion suffused their society and there was no stark distinction between religious and secular spheres. Sources on Punic religion are poor. There are no surviving literary sources and Punic religion is primarily reconstructed from inscriptions and archaeological evidence. An important sacred space in Punic religion appears to have been the large open air sanctuaries known as tophets in modern scholarship, in which urns containing the cremated bones of infants and animals were buried. There is a long-running scholarly debate about whether child sacrifice occurred at these locations, as suggested by Greco-Roman and biblical sources.

The Punic people, usually known as the Carthaginians, were a Semitic people who migrated from Phoenicia to the Western Mediterranean during the Early Iron Age. In modern scholarship, the term Punic, the Latin equivalent of the Greek-derived term Phoenician, is exclusively used to refer to Phoenicians in the western Mediterranean, following the line of the Greek East and Latin West. The largest Punic settlement was Ancient Carthage, but there were 300 other settlements along the North African coast from Leptis Magna in modern Libya to Mogador in southern Morocco, as well as western Sicily, southern Sardinia, the southern and eastern coasts of the Iberian Peninsula, Malta, and Ibiza. Their language, Punic, was a dialect of Phoenician, one of the Northwest Semitic languages originating in the Levant.

Ancient Carthage was an ancient Semitic civilisation based in North Africa. Initially a settlement in present-day Tunisia, it later became a city-state and then an empire. Founded by the Phoenicians in the ninth century BC, Carthage reached its height in the fourth century BC as one of the largest metropoleis in the world. It was the centre of the Carthaginian Empire, a major power led by the Punic people who dominated the ancient western and central Mediterranean Sea. Following the Punic Wars, Carthage was destroyed by the Romans in 146 BC, who later rebuilt the city lavishly.

Carthage National Museum is a national museum in Byrsa, Tunisia. Along with the Bardo National Museum, it is one of the two main local archaeological museums in the region. The edifice sits atop Byrsa Hill, in the heart of the city of Carthage. Founded in 1875, it houses many archaeological items from the Punic era and other periods.

The culture of the ancient Phoenicians was one of the first to have had a significant effect on the history of wine. Phoenicia was a civilization centered in current day Lebanon. Between 1550 BC and 300 BC, the Phoenicians developed a maritime trading culture that expanded their influence from the Levant to North Africa, the Greek Isles, Sicily, and the Iberian Peninsula. Through contact and trade, they spread not only their alphabet but also their knowledge of viticulture and winemaking, including the propagation of several ancestral varieties of the Vitis vinifera species of wine grapes.

Honor Frost was a pioneer in the field of underwater archaeology, who led many Mediterranean archaeological investigations, especially in Lebanon, and was noted for her typology of stone anchors and skills in archaeological illustration.

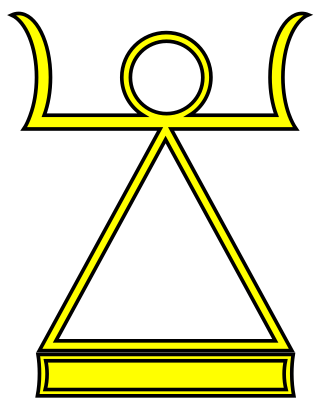

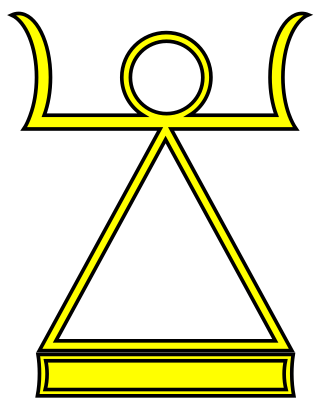

The sign of Tanit or sign of Tinnit is an anthropomorph symbol of the Punic goddess Tanit, present on many archaeological remains of the Carthaginian civilization.

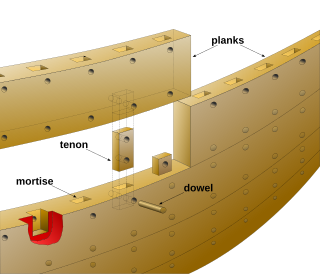

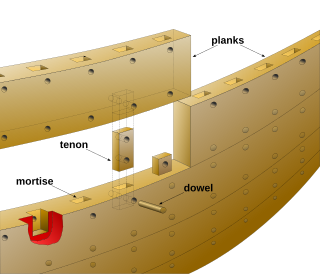

Phoenician joints is a locked mortise and tenon wood joinery technique used in shipbuilding to fasten watercraft hulls. The locked mortise and tenon technique consists of cutting a mortise, or socket, into the edges of two planks and fastening them together with a rectangular wooden knob. The assembly is then locked in place by driving a dowel through one or more holes drilled through the mortise side wall and tenon.

The Carthage Punic Ports were the old ports of the city of Carthage that were in operation during ancient times. Carthage was first and foremost a thalassocracy, that is, a power that was referred to as an Empire of the Seas, whose primary force was based on the scale of its trade. The Carthaginians, however, were not the only ones to follow that policy of control over the seas, since several of the people in those times "lived by and for the sea".

Ancient Rome had a variety of ships that played crucial roles in its military, trade, and transportation activities. Rome was preceded in the use of the sea by other ancient, seafaring civilizations of the Mediterranean. The galley was a long, narrow, highly maneuverable ship powered by oarsmen, sometimes stacked in multiple levels such as biremes or triremes, and many of which also had sails. Initial efforts of the Romans to construct a war fleet were based on copies of Carthaginian warships. In the Punic wars in the mid-third century BCE, the Romans were at first outclassed by Carthage at sea, but by 256 BCE had drawn even and fought the wars to a stalemate. In 55 BCE Julius Caesar used warships and transport ships to invade Britain. Numerous types of transport ships were used to carry foodstuffs or other trade goods around the Mediterranean, many of which did double duty and were pressed into service as warships or troop transports in time of war.

The Carthage tophet, is an ancient sacred area dedicated to the Phoenician deities Tanit and Baal, located in the Carthaginian district of Salammbô, Tunisia, near the Punic ports. This tophet, a "hybrid of sanctuary and necropolis", contains a large number of children's tombs which, according to some interpretations, were sacrificed or buried here after their untimely death. The area is part of the Carthage archaeological site, a UNESCO World Heritage site.

The Bajo de la Campana Phoenician shipwreck is a seventh-century-BC shipwreck of a Phoenician trade ship found at Bajo de la Campana, a submerged rock reef near Cartagena, Spain. This shipwreck was accidentally discovered in the 1950s. It is the earliest Phoenician shipwreck to date to undergo an archaeological excavation. Over the course of four field seasons, researchers conducted almost 4,000 dives and over 300 hours of exploration. The sunken ship spilled its cargo in and around an underwater cave at the edge of the Bajo reef. Among the artifacts recovered were fragments of the ship's hull, along with terracotta vessels, including amphoras, bowls, and plates. Among the cargo were elephant ivory tusks, indicating Phoenician trade connections with regions where elephants were native. Additionally, the discovery of tin ingots, copper ingots, and galena nuggets suggests the ship's involvement in long-distance trade networks. The cargo contained also pine cones, double-sided wooden combs, amber nodules from the Baltic, and various raw materials such as timber, and resin. Provisions and personal items of the crew were also recovered from the wreck, such as a gaming piece, a whetstone with Phoenician graffiti, and nuts and seeds. The Bajo de la Campana shipwreck belonged to Phoenician traders from the Eastern Mediterranean.