Related Research Articles

A cosmological argument, in natural theology, is an argument which claims that the existence of God can be inferred from facts concerning causation, explanation, change, motion, contingency, dependency, or finitude with respect to the universe or some totality of objects. A cosmological argument can also sometimes be referred to as an argument from universal causation, an argument from first cause, the causal argument, or prime mover argument. Whichever term is employed, there are two basic variants of the argument, each with subtle yet important distinctions: in esse (essentiality), and in fieri (becoming).

In philosophy, physicalism is the view that "everything is physical", that there is "nothing over and above" the physical, or that everything supervenes on the physical. Physicalism is a form of ontological monism—a "one substance" view of the nature of reality as opposed to a "two-substance" or "many-substance" (pluralism) view. Both the definition of "physical" and the meaning of physicalism have been debated.

Saul Aaron Kripke was an American analytic philosopher and logician. He was Distinguished Professor of Philosophy at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York and emeritus professor at Princeton University. Kripke is considered one of the most important philosophers of the latter half of the 20th century. Since the 1960s, he has been a central figure in a number of fields related to mathematical and modal logic, philosophy of language and mathematics, metaphysics, epistemology, and recursion theory.

Modal logic is a kind of logic used to represent statements about necessity and possibility. It plays a major role in philosophy and related fields as a tool for understanding concepts such as knowledge, obligation, and causation. For instance, in epistemic modal logic, the formula can be used to represent the statement that is known. In deontic modal logic, that same formula can represent that is a moral obligation.

The Critique of Pure Reason is a book by the German philosopher Immanuel Kant, in which the author seeks to determine the limits and scope of metaphysics. Also referred to as Kant's "First Critique", it was followed by his Critique of Practical Reason (1788) and Critique of Judgment (1790). In the preface to the first edition, Kant explains that by a "critique of pure reason" he means a critique "of the faculty of reason in general, in respect of all knowledge after which it may strive independently of all experience" and that he aims to reach a decision about "the possibility or impossibility of metaphysics". The term "critique" is understood to mean a systematic analysis in this context, rather than the colloquial sense of the term.

Hume's fork, in epistemology, is a tenet elaborating upon British empiricist philosopher David Hume's emphatic, 1730s division between "relations of ideas" and "matters of fact." As phrased in Immanuel Kant's 1780s characterization of Hume's thesis, and furthered in the 1930s by the logical empiricists, Hume's fork asserts that all statements are exclusively either "analytic a priori" or "synthetic a posteriori," which, respectively, are universally true by mere definition or, however apparently probable, are unknowable without exact experience.

Logical possibility refers to a logical proposition that cannot be disproved, using the axioms and rules of a given system of logic. The logical possibility of a proposition will depend upon the system of logic being considered, rather than on the violation of any single rule. Some systems of logic restrict inferences from inconsistent propositions or even allow for true contradictions. Other logical systems have more than two truth-values instead of a binary of such values. Some assume the system in question is classical propositional logic. Similarly, the criterion for logical possibility is often based on whether or not a proposition is contradictory and as such, is often thought of as the broadest type of possibility.

The existence of God is a subject of debate in theology and the philosophy of religion. A wide variety of arguments for and against the existence of God can be categorized as logical, empirical, metaphysical, subjective or scientific. In philosophical terms, the question of the existence of God involves the disciplines of epistemology and ontology and the theory of value.

A possible world is a complete and consistent way the world is or could have been. Possible worlds are widely used as a formal device in logic, philosophy, and linguistics in order to provide a semantics for intensional and modal logic. Their metaphysical status has been a subject of controversy in philosophy, with modal realists such as David Lewis arguing that they are literally existing alternate realities, and others such as Robert Stalnaker arguing that they are not.

Subjunctive possibility is a form of modality studied in modal logic. Subjunctive possibilities are the sorts of possibilities considered when conceiving counterfactual situations; subjunctive modalities are modalities that bear on whether a statement might have been or could be true—such as might, could, must, possibly, necessarily, contingently, essentially, accidentally, and so on. Subjunctive possibilities include logical possibility, metaphysical possibility, nomological possibility, and temporal possibility.

Modal realism is the view propounded by philosopher David Lewis that all possible worlds are real in the same way as is the actual world: they are "of a kind with this world of ours." It is based on four tenets: possible worlds exist, possible worlds are not different in kind from the actual world, possible worlds are irreducible entities, and the term actual in actual world is indexical, i.e. any subject can declare their world to be the actual one, much as they label the place they are "here" and the time they are "now".

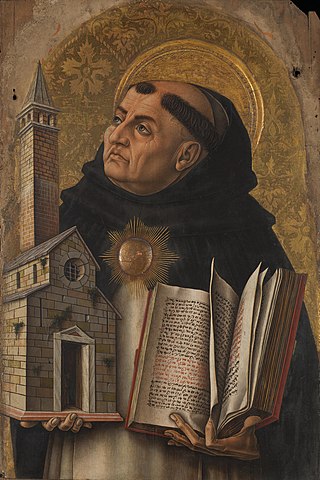

The Quinque viæ are five logical arguments for the existence of God summarized by the 13th-century Catholic philosopher and theologian Thomas Aquinas in his book Summa Theologica. They are:

- the argument from "first mover";

- the argument from universal causation;

- the argument from contingency;

- the argument from degree;

- the argument from final cause or ends.

The analytic–synthetic distinction is a semantic distinction used primarily in philosophy to distinguish between propositions that are of two types: analytic propositions and synthetic propositions. Analytic propositions are true or not true solely by virtue of their meaning, whereas synthetic propositions' truth, if any, derives from how their meaning relates to the world.

A priori and a posteriori are Latin phrases used in philosophy to distinguish types of knowledge, justification, or argument by their reliance on experience. A priori knowledge is independent from any experience. Examples include mathematics, tautologies and deduction from pure reason. A posteriori knowledge depends on empirical evidence. Examples include most fields of science and aspects of personal knowledge.

Naming and Necessity is a 1980 book with the transcript of three lectures, given by the philosopher Saul Kripke, at Princeton University in 1970, in which he dealt with the debates of proper names in the philosophy of language. The transcript was brought out originally in 1972 in Semantics of Natural Language, edited by Donald Davidson and Gilbert Harman. Among analytic philosophers, Naming and Necessity is widely considered one of the most important philosophical works of the twentieth century.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to metaphysics:

In logic, contingency is the feature of a statement making it neither necessary nor impossible. Contingency is a fundamental concept of modal logic. Modal logic concerns the manner, or mode, in which statements are true. Contingency is one of three basic modes alongside necessity and possibility. In modal logic, a contingent statement stands in the modal realm between what is necessary and what is impossible, never crossing into the territory of either status. Contingent and necessary statements form the complete set of possible statements. While this definition is widely accepted, the precise distinction between what is contingent and what is necessary has been challenged since antiquity.

An ontological argument is a philosophical argument, made from an ontological basis, that is advanced in support of the existence of God. Such arguments tend to refer to the state of being or existing. More specifically, ontological arguments are commonly conceived a priori in regard to the organization of the universe, whereby, if such organizational structure is true, God must exist.

A posteriori necessity is a thesis in metaphysics and the philosophy of language, that some statements of which we must acquire knowledge a posteriori are also necessarily true. It challenges previously widespread belief that only a priori knowledge can be necessary. It draws on a number of philosophical concepts such as necessity, the causal theory of reference, rigidity, and the a priori–a posteriori distinction.

Humeanism refers to the philosophy of David Hume and to the tradition of thought inspired by him. Hume was an influential Scottish philosopher well known for his empirical approach, which he applied to various fields in philosophy. In the philosophy of science, he is notable for developing the regularity theory of causation, which in its strongest form states that causation is nothing but constant conjunction of certain types of events without any underlying forces responsible for this regularity of conjunction. This is closely connected to his metaphysical thesis that there are no necessary connections between distinct entities. The Humean theory of action defines actions as bodily behavior caused by mental states and processes without the need to refer to an agent responsible for this. The slogan of Hume's theory of practical reason is that "reason is...the slave of the passions". It restricts the sphere of practical reason to instrumental rationality concerning which means to employ to achieve a given end. But it denies reason a direct role regarding which ends to follow. Central to Hume's position in metaethics is the is-ought distinction. It states that is-statements, which concern facts about the natural world, do not imply ought-statements, which are moral or evaluative claims about what should be done or what has value. In philosophy of mind, Hume is well known for his development of the bundle theory of the self. It states that the self is to be understood as a bundle of mental states and not as a substance acting as the bearer of these states, as is the traditional conception. Many of these positions were initially motivated by Hume's empirical outlook. It emphasizes the need to ground one's theories in experience and faults opposing theories for failing to do so. But many philosophers within the Humean tradition have gone beyond these methodological restrictions and have drawn various metaphysical conclusions from Hume's ideas.

References

- ↑ Brian Leftow, God and Necessity (2012). ISBN 0191654876, 9780191654879

- ↑ John Hick (1961): Necessary Being. - Scottish Journal of Theology, 1961: 353-369.

- ↑ William L. Rowe (1998): The Cosmological Argument. Fordham Univ Press, 273 pp.

- 1 2 Hume, David (1739). "Book I, Part III, Section VI". A Treatise of Human Nature. The Project Gutenberg.

- ↑ Lewis, David (1986). On the Plurality of Worlds. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 88.

- ↑ Gibbs, Cameron (2019). "6. THE ARGUMENT FROM PLENITUDE". A Defense of Hume's Dictum.

- ↑ Swartz, Norman. Laws of Nature . Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Bird, Alexander (2001). "Necessarily, Salt Dissolves in Water". Analysis. 61 (4): 267–274. doi:10.1111/1467-8284.00304.

- ↑ Gibbs, Cameron (2019). "2. CONSTRAINTS ON FORMULATING HUME'S DICTUM". A Defense of Hume's Dictum.

- ↑ Menzel, Christopher (2017). Possible Worlds. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 28 November 2020.

- ↑ Kripke, Saul. 1980. Naming and Necessity. Harvard University Press: 22.

- ↑ Ronald H. Nash (1983): The Concept of God. Grand Rapids, MI: Zondervan, p. 108

- ↑ Richard Swinburne (2004): The Existence of God. 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 96