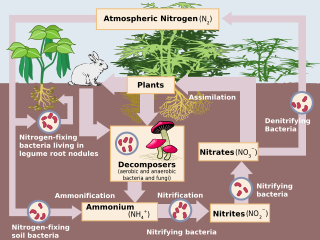

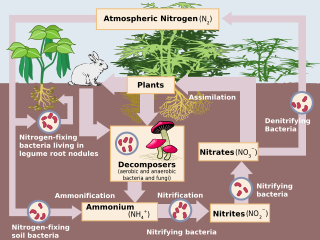

Nitrification is the biological oxidation of ammonia to nitrate via the intermediary nitrite. Nitrification is an important step in the nitrogen cycle in soil. The process of complete nitrification may occur through separate organisms or entirely within one organism, as in comammox bacteria. The transformation of ammonia to nitrite is usually the rate limiting step of nitrification. Nitrification is an aerobic process performed by small groups of autotrophic bacteria and archaea.

Anaerobic respiration is respiration using electron acceptors other than molecular oxygen (O2). Although oxygen is not the final electron acceptor, the process still uses a respiratory electron transport chain.

Methanogenesis or biomethanation is the formation of methane coupled to energy conservation by microbes known as methanogens. Organisms capable of producing methane for energy conservation have been identified only from the domain Archaea, a group phylogenetically distinct from both eukaryotes and bacteria, although many live in close association with anaerobic bacteria. The production of methane is an important and widespread form of microbial metabolism. In anoxic environments, it is the final step in the decomposition of biomass. Methanogenesis is responsible for significant amounts of natural gas accumulations, the remainder being thermogenic.

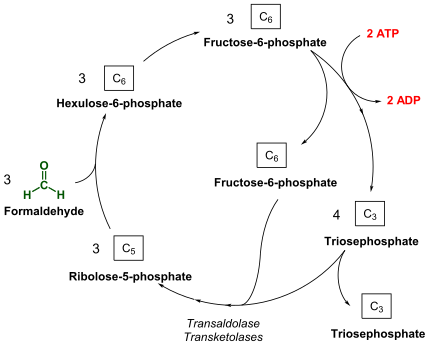

Methylotrophs are a diverse group of microorganisms that can use reduced one-carbon compounds, such as methanol or methane, as the carbon source for their growth; and multi-carbon compounds that contain no carbon-carbon bonds, such as dimethyl ether and dimethylamine. This group of microorganisms also includes those capable of assimilating reduced one-carbon compounds by way of carbon dioxide using the ribulose bisphosphate pathway. These organisms should not be confused with methanogens which on the contrary produce methane as a by-product from various one-carbon compounds such as carbon dioxide. Some methylotrophs can degrade the greenhouse gas methane, and in this case they are called methanotrophs. The abundance, purity, and low price of methanol compared to commonly used sugars make methylotrophs competent organisms for production of amino acids, vitamins, recombinant proteins, single-cell proteins, co-enzymes and cytochromes.

Denitrifying bacteria are a diverse group of bacteria that encompass many different phyla. This group of bacteria, together with denitrifying fungi and archaea, is capable of performing denitrification as part of the nitrogen cycle. Denitrification is performed by a variety of denitrifying bacteria that are widely distributed in soils and sediments and that use oxidized nitrogen compounds such as nitrate and nitrite in the absence of oxygen as a terminal electron acceptor. They metabolize nitrogenous compounds using various enzymes, including nitrate reductase (NAR), nitrite reductase (NIR), nitric oxide reductase (NOR) and nitrous oxide reductase (NOS), turning nitrogen oxides back to nitrogen gas or nitrous oxide.

Methane monooxygenase (MMO) is an enzyme capable of oxidizing the C-H bond in methane as well as other alkanes. Methane monooxygenase belongs to the class of oxidoreductase enzymes.

Microbial metabolism is the means by which a microbe obtains the energy and nutrients it needs to live and reproduce. Microbes use many different types of metabolic strategies and species can often be differentiated from each other based on metabolic characteristics. The specific metabolic properties of a microbe are the major factors in determining that microbe's ecological niche, and often allow for that microbe to be useful in industrial processes or responsible for biogeochemical cycles.

Methylobacillus flagellatus is a species of aerobic bacteria.

A chemocline is a type of cline, a layer of fluid with different properties, characterized by a strong, vertical chemistry gradient within a body of water. In bodies of water where chemoclines occur, the cline separates the upper and lower layers, resulting in different properties for those layers. The lower layer shows a change in the concentration of dissolved gases and solids compared to the upper layer.

Anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM) is a methane-consuming microbial process occurring in anoxic marine and freshwater sediments. AOM is known to occur among mesophiles, but also in psychrophiles, thermophiles, halophiles, acidophiles, and alkophiles. During AOM, methane is oxidized with different terminal electron acceptors such as sulfate, nitrate, nitrite and metals, either alone or in syntrophy with a partner organism.

Methylocella silvestris is a bacterium from the genus Methylocella spp which are found in many acidic soils and wetlands. Historically, Methylocella silvestris was originally isolated from acidic forest soils in Germany, and it is described as Gram-negative, aerobic, non-pigmented, non-motile, rod-shaped and methane-oxidizing facultative methanotroph. As an aerobic methanotrophic bacteria, Methylocella spp use methane (CH4), and methanol as their main carbon and energy source, as well as multi compounds acetate, pyruvate, succinate, malate, and ethanol. They were known to survive in the cold temperature from 4° to 30° degree of Celsius with the optimum at around 15° to 25 °C, but no more than 36 °C. They grow better in the pH scale between 4.5 to 7.0. It lacks intracytoplasmic membranes common to all methane-oxidizing bacteria except Methylocella, but contain a vesicular membrane system connected to the cytoplasmic membrane. BL2T (=DSM 15510T=NCIMB 13906T) is the type strain.

Methylocapsa acidiphila is a bacterium. It is a methane-oxidizing and dinitrogen-fixing acidophilic bacterium first isolated from Sphagnum bog. Its cells are aerobic, gram-negative, colourless, non-motile, curved coccoids that form conglomerates covered by an extracellular polysaccharide matrix. The cells use methane and methanol as sole sources of carbon and energy. B2T is the type strain.

Methylosinus trichosporium is an obligate aerobic and methane-oxidizing bacterium species from the genus of Methylosinus. Its native habitat is generally in the soil, but the bacteria has been isolated from fresh water sediments and groundwater as well. Because of this bacterium's ability to oxidize methane, M. trichosporium has been popular for identifying both the structure and function of enzymes involved with methane oxidation since it was first isolated in 1970 by Roger Whittenbury and colleagues. Since its discovery, M. trichosporium and its soluble monooxygenase enzyme have been studied in detail to see if the bacterium could help in bioremediation treatments.

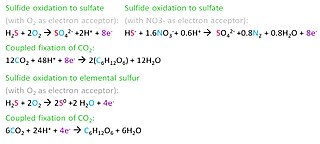

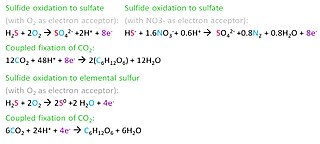

Microbial oxidation of sulfur is the oxidation of sulfur by microorganisms to build their structural components. The oxidation of inorganic compounds is the strategy primarily used by chemolithotrophic microorganisms to obtain energy to survive, grow and reproduce. Some inorganic forms of reduced sulfur, mainly sulfide (H2S/HS−) and elemental sulfur (S0), can be oxidized by chemolithotrophic sulfur-oxidizing prokaryotes, usually coupled to the reduction of oxygen (O2) or nitrate (NO3−). Anaerobic sulfur oxidizers include photolithoautotrophs that obtain their energy from sunlight, hydrogen from sulfide, and carbon from carbon dioxide (CO2).

The sulfate-methane transition zone (SMTZ) is a zone in oceans, lakes, and rivers typically found below the sediment surface in which sulfate and methane coexist. The formation of a SMTZ is driven by the diffusion of sulfate down the sediment column and the diffusion of methane up the sediments. At the SMTZ, their diffusion profiles meet and sulfate and methane react with one another, which allows the SMTZ to harbor a unique microbial community whose main form of metabolism is anaerobic oxidation of methane (AOM). The presence of AOM marks the transition from dissimilatory sulfate reduction to methanogenesis as the main metabolism utilized by organisms.

An oxygen minimum zone (OMZ) is characterized as an oxygen-deficient layer in the world's oceans. Typically found between 200m to 1500m deep below regions of high productivity, such as the western coasts of continents. OMZs can be seasonal following the spring-summer upwelling season. Upwelling of nutrient-rich water leads to high productivity and labile organic matter, that is respired by heterotrophs as it sinks down the water column. High respiration rates deplete the oxygen in the water column to concentrations of 2 mg/L or less forming the OMZ. OMZs are expanding, with increasing ocean deoxygenation. Under these oxygen-starved conditions, energy is diverted from higher trophic levels to microbial communities that have evolved to use other biogeochemical species instead of oxygen, these species include Nitrate, Nitrite, Sulphate etc. Several Bacteria and Archea have adapted to live in these environments by using these alternate chemical species and thrive. The most abundant phyla in OMZs are Pseudomonadota, Bacteroidota, Actinomycetota, and Planctomycetota.

The hydrothermal vent microbial community includes all unicellular organisms that live and reproduce in a chemically distinct area around hydrothermal vents. These include organisms in the microbial mat, free floating cells, or bacteria in an endosymbiotic relationship with animals. Chemolithoautotrophic bacteria derive nutrients and energy from the geological activity at Hydrothermal vents to fix carbon into organic forms. Viruses are also a part of the hydrothermal vent microbial community and their influence on the microbial ecology in these ecosystems is a burgeoning field of research.

NC10 is a bacterial phylum with candidate status, meaning its members remain uncultured to date. The difficulty in producing lab cultures may be linked to low growth rates and other limiting growth factors.

Candidatus "Methylomirabilis oxyfera" is a candidate species of Gram-negative bacteria belonging to the NC10 phylum, characterized for its capacity to couple anaerobic methane oxidation with nitrite reduction in anoxic environments. To acquire oxygen for methane oxidation, M. oxyfera utilizes an intra-aerobic pathway through the reduction of nitrite (NO2) to dinitrogen (N2) and oxygen.

Methanoperedens nitroreducens is a candidate species of methanotrophic archaea that oxidizes methane by coupling to nitrate reduction.