In politics, lobbying, or advocacy, is the act of lawfully attempting to influence the actions, policies, or decisions of government officials, most often legislators or members of regulatory agencies, but also judges of the judiciary. Lobbying, which usually involves direct, face-to-face contact in cooperation with support staff that may not meet directly face-to-face, is done by many types of people, associations and organized groups, including individuals on a personal level in their capacity as voters, constituents, or private citizens; it is also practiced by corporations in the private sector serving their own business interests; by non-profits and non-governmental organizations in the voluntary sector through advocacy groups to fulfil their mission such as requesting humanitarian aid or grantmaking; and by fellow legislators or government officials influencing each other through legislative affairs in the public sector.

Public choice, or public choice theory, is "the use of economic tools to deal with traditional problems of political science." Its content includes the study of political behavior. In political science, it is the subset of positive political theory that studies self-interested agents and their interactions, which can be represented in a number of ways—using standard constrained utility maximization, game theory, or decision theory. It is the origin and intellectual foundation of contemporary work in political economy.

Advocacy is an activity by an individual or group that aims to influence decisions within political, economic, and social institutions. Advocacy includes activities and publications to influence public policy, laws and budgets by using facts, their relationships, the media, and messaging to educate government officials and the public. Advocacy can include many activities that a person or organization undertakes, including media campaigns, public speaking, commissioning and publishing research. Lobbying is a form of advocacy where a direct approach is made to legislators on a specific issue or specific piece of legislation. Research has started to address how advocacy groups in the United States and Canada are using social media to facilitate civic engagement and collective action.

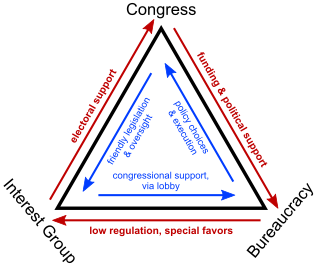

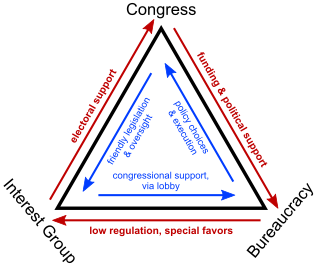

In United States politics, the "iron triangle" comprises the policy-making relationship among the congressional committees, the bureaucracy, and interest groups, as described in 1981 by Gordon Adams. Earlier mentions of this ‘iron triangle’ concept are in a 1956 Congressional Quarterly Weekly Report as, “Iron triangle: Clout, background, and outlook” and “Chinks in the Iron Triangle?”

Single-issue politics involves political campaigning or political support based on one essential policy area or idea.

Domestic policy, also known as internal policy, is a type of public policy overseeing administrative decisions that are directly related to all issues and activity within a state's borders. It differs from foreign policy, which refers to the ways a government advances its interests in external politics. Domestic policy covers a wide range of areas, including business, education, energy, healthcare, law enforcement, money and taxes, natural resources, social welfare, and personal rights and freedoms.

Lobbying in the United States describes paid activity in which special interest groups hire well-connected professional advocates, often lawyers, to argue for specific legislation in decision-making bodies such as the United States Congress. It is often perceived negatively by journalists and the American public; critics consider it to be a form of bribery, influence peddling, and/or extortion. Lobbying is subject to complex rules which, if not followed, can lead to penalties including jail. Lobbying has been interpreted by court rulings as free speech protected by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Since the 1970s, the numbers of lobbyists and the size of lobbying budgets has grown and become the focus of criticism of American governance.

The Arab lobby in the United States is a collection of formal and informal groups and professional lobbyists in the United States paid directly by Gulf Arab states and private donors on behalf of the Arab states.

A civil society campaign is one that is intended to mobilize public support and use democratic tools such as lobbying in order to instigate social change. Civil society campaigns can seek local, national or international objectives. They can be run by dedicated single-issue groups such as Baby Milk Action, or by professional non-governmental organisations (NGOs), such as the World Development Movement, who may have several campaigns running at any one time. Larger coalition campaigns such as 2005's Make Poverty History may involve a combination of NGOs.

LGBT movements in the United States comprise an interwoven history of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and allied social movements in the United States of America, beginning in the early 20th century. A commonly stated goal among these movements is social equality for LGBT people. Some have also focused on building LGBT communities or worked towards liberation for the broader society from biphobia, homophobia, and transphobia. LGBT movements organized today are made up of a wide range of political activism and cultural activity, including lobbying, street marches, social groups, media, art, and research. Sociologist Mary Bernstein writes: "For the lesbian and gay movement, then, cultural goals include challenging dominant constructions of masculinity and femininity, homophobia, and the primacy of the gendered heterosexual nuclear family (heteronormativity). Political goals include changing laws and policies in order to gain new rights, benefits, and protections from harm." Bernstein emphasizes that activists seek both types of goals in both the civil and political spheres.

Equality NC(ENC) is the largest lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender rights advocacy group and political lobbying organization in North Carolina and is the oldest statewide LGBT equality organization in the United States.

Lobbying in the United Kingdom plays a significant role in the formation of legislation and a wide variety of commercial organisations, lobby groups "lobby" for particular policies and decisions by Parliament and other political organs at national, regional and local levels.

Advocacy groups, also known as lobby groups, interest groups, special interest groups, pressure groups, or public associations, use various forms of advocacy or lobbying to influence public opinion and ultimate public policy. They play an important role in the development of political and social systems.

Grassroots lobbying is lobbying with the intention of reaching the legislature and making a difference in the decision-making process. Grassroots lobbying is an approach that separates itself from direct lobbying through the act of asking the general public to contact legislators and government officials concerning the issue at hand, as opposed to conveying the message to the legislators directly. Companies, associations and citizens are increasingly partaking in grassroots lobbying as an attempt to influence a change in legislation.

Direct lobbying in the United States are methods used by lobbyists to influence United States legislative bodies. Interest groups from many sectors spend billions of dollars on lobbying.

The Fairness Campaign is a Louisville, Kentucky-based lobbying and advocacy organization, focusing primarily on preventing discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation and gender identity. The Fairness Campaign is recognized by the IRS as a 501(c)(4) organization. The organization is a member of the Equality Federation.

An advocacy group is a group or an organization that tries to influence the government but does not hold power in the government. Advocacy groups are generally classified according to two broad typologies: their core aims, and their relationship to government.

Lobbying in Canada is an activity where organizations or people outside of government attempt to influence the decision making of elected politicians or government officials at the municipal, provincial or federal level.