An incest taboo is any cultural rule or norm that prohibits sexual relations between certain members of the same family, mainly between individuals related by blood. All human cultures have norms that exclude certain close relatives from those considered suitable or permissible sexual or marriage partners, making such relationships taboo. However, different norms exist among cultures as to which blood relations are permissible as sexual partners and which are not. Sexual relations between related persons which are subject to the taboo are called incestuous relationships.

Exogamy is the social norm of mating or marrying outside one's social group. The group defines the scope and extent of exogamy, and the rules and enforcement mechanisms that ensure its continuity. One form of exogamy is dual exogamy, in which two groups continually intermarry with each other.

In anthropology, kinship is the web of social relationships that form an important part of the lives of all humans in all societies, although its exact meanings even within this discipline are often debated. Anthropologist Robin Fox says that the study of kinship is the study of what humans do with these basic facts of life – mating, gestation, parenthood, socialization, siblingship etc. Human society is unique, he argues, in that we are "working with the same raw material as exists in the animal world, but [we] can conceptualize and categorize it to serve social ends." These social ends include the socialization of children and the formation of basic economic, political and religious groups.

A wet nurse is a woman who breastfeeds and cares for another's child. Wet nurses are employed if the mother dies, or if she is unable or chooses not to nurse the child herself. Wet-nursed children may be known as "milk-siblings", and in some cultures, the families are linked by a special relationship of milk kinship. Wet-nursing existed in cultures around the world until the invention of reliable formula milk in the 20th century. The practice has made a small comeback in the 21st century.

In denominations of Christianity, a godparent or sponsor is someone who bears witness to a child's baptism (christening) and later is willing to help in their catechesis, as well as their lifelong spiritual formation. In the past, in some countries, the role carried some legal obligations as well as religious responsibilities. In both religious and civil views, a godparent tends to be an individual chosen by the parents to take an interest in the child's upbringing and personal development, to offer mentorship or claim legal guardianship of the child if anything should happen to the parents. A male godparent is a godfather, and a female godparent is a godmother. The child is a godchild.

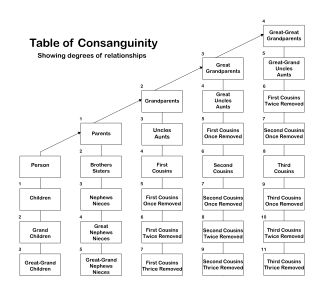

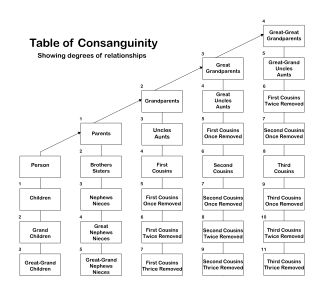

Consanguinity is the characteristic of having a kinship with a relative who is descended from a common ancestor.

Ambilineality is a form of kinship affiliation of cognatic descent that relies on self-defined affiliation within a given social system, meaning individuals have the choice to be affiliated with their mother's or father's group. Common features of societies that practice ambilineality are a shared set of land, communal responsibilities, and collective ownership of some segments of wealth and debt in their societies. This system of descent is distinct from more common genealogical structures in that rather than determining affiliation and descent using the standard determinants of biological and genealogical relation, it instead relies heavily on voluntary affiliation with one's group, oftentimes being determined by factors including residence.

In Islam, a mahram is a family member with whom marriage would be considered permanently unlawful (haram). A woman does not need to wear hijab around her mahram or spouse, and an adult male mahram or husband may escort a woman on a journey, although an escort may not be obligatory.

Fictive kinship is a term used by anthropologists and ethnographers to describe forms of kinship or social ties that are based on neither consanguineal nor affinal ties. It contrasts with true kinship ties.

In discussing consanguineal kinship in anthropology, a parallel cousin or ortho-cousin is a cousin from a parent's same-sex sibling, while a cross-cousin is from a parent's opposite-sex sibling. Thus, a parallel cousin is the child of the father's brother or of the mother's sister, while a cross-cousin is the child of the mother's brother or of the father's sister. Where there are unilineal descent groups in a society, one's parallel cousins on one or both sides will belong to one's own descent group, while cross-cousins will not.

Halima bint Abi Dhu'ayb al-Sa'diyya was the foster-mother of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. Halimah and her husband were from the tribe of Sa'd b. Bakr, a subdivision of Hawazin.

Alliance theory, also known as the general theory of exchanges, is a structuralist method of studying kinship relations. It finds its origins in Claude Lévi-Strauss's Elementary Structures of Kinship (1949) and is in opposition to the functionalist theory of Radcliffe-Brown. Alliance theory has oriented most anthropological French works until the 1980s; its influences were felt in various fields, including psychoanalysis, philosophy and political philosophy.

Erotic lactation is sexual arousal by breastfeeding on a woman's breast. Depending on the context, the practice can also be referred to as adult suckling, adult nursing, and adult breastfeeding. Practitioners sometimes refer to themselves as being in an adult nursing relationship (ANR). Two persons in an exclusive relationship can be called a nursing couple.

The history and culture of breastfeeding traces changing social, medical and legal attitudes to breastfeeding, the act of feeding a child breast milk directly from breast to mouth. Breastfeeding may be performed by the infant's mother or by a surrogate, typically called a wet nurse.

Breastfeeding is highly regarded in Islam. The Qur'an regards it as a sign of love between the mother and child. In Islamic law, breastfeeding creates ties of milk kinship that has implications in family law. Muslims throughout the world have varied breastfeeding traditions.

Breastfeeding, or nursing, is the process by which human breast milk is fed to a child. Breast milk may be from the breast, or may be pumped and fed to the infant. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that breastfeeding begin within the first hour of a baby's life and continue as often and as much as the baby wants. Health organizations, including the WHO, recommend breastfeeding exclusively for six months. This means that no other foods or drinks, other than vitamin D, are typically given. The WHO recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first 6 months of life, followed by continued breastfeeding with appropriate complementary foods for up to 2 years and beyond. Of the 135 million babies born every year, only 42% are breastfed within the first hour of life, only 38% of mothers practice exclusive breastfeeding during the first six months, and 58% of mothers continue breastfeeding up to the age of two years and beyond.

The concept of nurture kinship in the anthropological study of human social relationships (kinship) highlights the extent to which such relationships are brought into being through the performance of various acts of nurture between individuals. Additionally the concept highlights ethnographic findings that, in a wide swath of human societies, people understand, conceptualize and symbolize their relationships predominantly in terms of giving, receiving and sharing nurture. The concept stands in contrast to the earlier anthropological concepts of human kinship relations being fundamentally based on "blood ties", some other form of shared substance, or a proxy for these, and the accompanying notion that people universally understand their social relationships predominantly in these terms.

Human to animal breastfeeding has been practiced in some different cultures during various time periods. The practice of breastfeeding or suckling between humans and other species occurred in both directions: women sometimes breastfed young animals, and animals were used to suckle babies and children. Animals were used as substitute wet nurses for infants, particularly after the rise of syphilis increased the health risks of wet nursing. Goats and donkeys were widely used to feed abandoned babies in foundling hospitals in 18th- and 19th-century Europe. Breastfeeding animals has also been practised, whether for perceived health reasons – such as to toughen the nipples and improve the flow of milk – or for religious and cultural purposes. A wide variety of animals have been used for this purpose, including puppies, kittens, piglets and monkeys.

Islamic family jurisprudence or Islamic family law or Muslim Family Law is the fiqh of laws and regulations related to maintaining of Muslim family, which are taken from Quran, hadith, fatwas of Muslim jurists and ijma of the Muslims. It contains pubertal, marital, sexual, child upbringing, adoption and fostering, inheritance, criminal and other related subjects. The subject mainly discusses on foster relationship, marriage, divorce, Ila, li'an, Raj'ah, Khul', Zihar, Iddah, custody and maintenance of children etc. From the political aspects, Muslim family law is a part of almost every national constitution of the world regarding religious (Muslim) laws, especially of the Muslim-majority countries.

Allomothering, or allomaternal care, is parental care provided by group members other than the genetic mother. This is a common feature of many cooperative breeding species, including some mammal, bird and insect species. Allomothering in humans is universal, but the members who participate in allomothering vary from culture to culture. Common allomothers are grandmothers, older siblings, extended family members, members of religious communities and ritual kin.