Islamic art is a part of Islamic culture and encompasses the visual arts produced since the 7th century CE by people who lived within territories inhabited or ruled by Muslim populations. Referring to characteristic traditions across a wide range of lands, periods, and genres, Islamic art is a concept used first by Western art historians in the late 19th century. Public Islamic art is traditionally non-representational, except for the widespread use of plant forms, usually in varieties of the spiralling arabesque. These are often combined with Islamic calligraphy, geometric patterns in styles that are typically found in a wide variety of media, from small objects in ceramic or metalwork to large decorative schemes in tiling on the outside and inside of large buildings, including mosques. Other forms of Islamic art include Islamic miniature painting, artefacts like Islamic glass or pottery, and textile arts, such as carpets and embroidery.

The medieval art of the Western world covers a vast scope of time and place, with over 1000 years of art in Europe, and at certain periods in Western Asia and Northern Africa. It includes major art movements and periods, national and regional art, genres, revivals, the artists' crafts, and the artists themselves.

Relief is a sculptural method in which the sculpted pieces remain attached to a solid background of the same material. The term relief is from the Latin verb relevare, to raise. To create a sculpture in relief is to give the impression that the sculpted material has been raised above the background plane. When a relief is carved into a flat surface of stone or wood, the field is actually lowered, leaving the unsculpted areas seeming higher. The approach requires a lot of chiselling away of the background, which takes a long time. On the other hand, a relief saves forming the rear of a subject, and is less fragile and more securely fixed than a sculpture in the round, especially one of a standing figure where the ankles are a potential weak point, particularly in stone. In other materials such as metal, clay, plaster stucco, ceramics or papier-mâché the form can be simply added to or raised up from the background. Monumental bronze reliefs are made by casting.

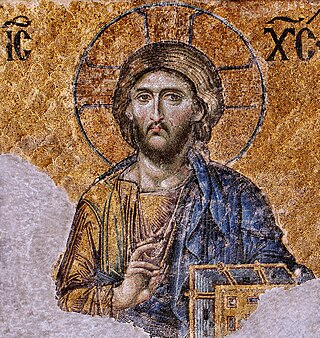

Byzantine art comprises the body of artistic products of the Eastern Roman Empire, as well as the nations and states that inherited culturally from the empire. Though the empire itself emerged from the decline of western Rome and lasted until the Fall of Constantinople in 1453, the start date of the Byzantine period is rather clearer in art history than in political history, if still imprecise. Many Eastern Orthodox states in Eastern Europe, as well as to some degree the Islamic states of the eastern Mediterranean, preserved many aspects of the empire's culture and art for centuries afterward.

Anglo-Saxon art covers art produced within the Anglo-Saxon period of English history, beginning with the Migration period style that the Anglo-Saxons brought with them from the continent in the 5th century, and ending in 1066 with the Norman Conquest of England, whose sophisticated art was influential in much of northern Europe. The two periods of outstanding achievement were the 7th and 8th centuries, with the metalwork and jewellery from Sutton Hoo and a series of magnificent illuminated manuscripts, and the final period after about 950, when there was a revival of English culture after the end of the Viking invasions. By the time of the Conquest the move to the Romanesque style is nearly complete. The important artistic centres, in so far as these can be established, were concentrated in the extremities of England, in Northumbria, especially in the early period, and Wessex and Kent near the south coast.

Romanesque art is the art of Europe from approximately 1000 AD to the rise of the Gothic style in the 12th century, or later depending on region. The preceding period is known as the Pre-Romanesque period. The term was invented by 19th-century art historians, especially for Romanesque architecture, which retained many basic features of Roman architectural style – most notably round-headed arches, but also barrel vaults, apses, and acanthus-leaf decoration – but had also developed many very different characteristics. In Southern France, Spain, and Italy there was an architectural continuity with the Late Antique, but the Romanesque style was the first style to spread across the whole of Catholic Europe, from Sicily to Scandinavia. Romanesque art was also greatly influenced by Byzantine art, especially in painting, and by the anti-classical energy of the decoration of the Insular art of the British Isles. From these elements was forged a highly innovative and coherent style.

Ivory carving is the carving of ivory, that is to say animal tooth or tusk, generally by using sharp cutting tools, either mechanically or manually. Objects carved in ivory are often called "ivories".

The Palatine Chapel is the royal chapel of the Norman Palace in Palermo, Sicily. This building is a mixture of Byzantine, Norman and Fatimid architectural styles, showing the tricultural state of Sicily during the 12th century after Roger I and Robert Guiscard conquered the island.

Olifant was the name applied in the Middle Ages to a type of carved ivory hunting horn created from elephant tusks. Olifants were most prominently used in Europe from roughly the tenth to the sixteenth century, although some were created later. The surviving inventories of Renaissance treasuries and armories document that Europeans, especially in France, Germany and England, owned trumpets in a variety of media and were used to signal, both in war and hunting. They were manufactured primarily in Italy, but towards the end of the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, they were also made in Africa for a European market. Typically, they were made with relief carvings that showed animal and human combat scenes, hunting scenes, fantastic beasts, and European heraldry. About seventy-five ivory hunting horns survive and about half can be found in museums and church treasuries, while others are in private collections or their locations remain unknown.

The Gebel el-Arak Knife, also Jebel el-Arak Knife, is an ivory and flint knife dating from the Naqada II period of Egyptian prehistory, showing Mesopotamian influence. The knife was purchased in 1914 in Cairo by Georges Aaron Bénédite for the Louvre, where it is now on display in the Sully wing, room 633. At the time of its purchase, the knife handle was alleged by the seller to have been found at the site of Gebel el-Arak, but it is today believed to come from Abydos.

The term Norman–Arab–Byzantine culture, Norman–Sicilian culture or, less inclusively, Norman–Arab culture, refers to the interaction of the Norman, Byzantine Greek, Latin, and Arab cultures following the Norman conquest of the former Emirate of Sicily and North Africa from 1061 to around 1250. The civilization resulted from numerous exchanges in the cultural and scientific fields, based on the tolerance shown by the Normans towards the Latin- and Greek-speaking Christian populations and the former Arab Muslim settlers. As a result, Sicily under the Normans became a crossroad for the interaction between the Norman and Latin Catholic, Byzantine–Orthodox, and Arab–Islamic cultures.

The Veroli Casket is a Middle Byzantine casket, probably made in Constantinople in the late 10th or early 11th century, and now in Room 8 of the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. It is thought to have been made for a person close to the Imperial Court of Constantinople, the capital of the Byzantine Empire, and may have been used to hold scent bottles or jewellery. It was later in the Cathedral Treasury at Veroli, south east of Rome, until 1861.

Fatimid art refers to artifacts and architecture from the Fatimid Caliphate (909–1171), an empire based in Egypt and North Africa. The Fatimid Caliphate was initially established in the Maghreb, with its roots in a ninth-century Shia Ismailist uprising. Many monuments survive in the Fatimid cities founded in North Africa, starting with Mahdia, on the Tunisian coast, the principal city prior to the conquest of Egypt in 969 and the building of al-Qahira, the "City Victorious", now part of modern-day Cairo. The period was marked by a prosperity amongst the upper echelons, manifested in the creation of opulent and finely wrought objects in the decorative arts, including carved rock crystal, lustreware and other ceramics, wood and ivory carving, gold jewelry and other metalware, textiles, books and coinage. These items not only reflected personal wealth, but were used as gifts to curry favour abroad. The most precious and valuable objects were amassed in the caliphal palaces in al-Qahira. In the 1060s, following several years of drought during which the armies received no payment, the palaces were systematically looted. The libraries were largely destroyed and precious gold objects were melted down, with a few of the treasures dispersed across the medieval Christian world. Afterwards, Fatimid artifacts continued to be made in the same style, but were adapted to a larger populace, using less precious materials.

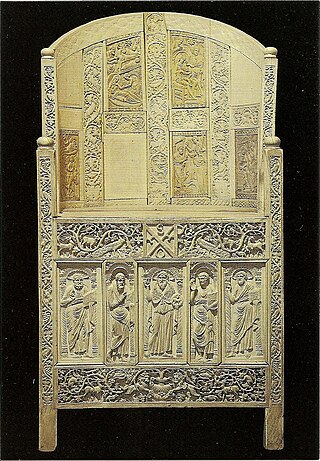

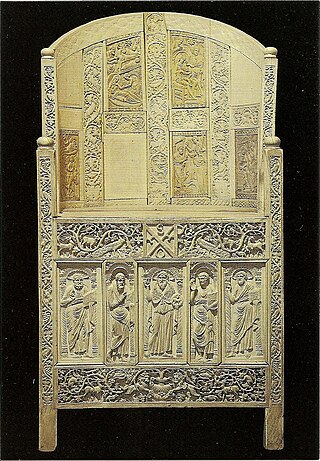

The Throne of Maximian is a cathedra that was made for Archbishop Maximianus of Ravenna and is now on display at the Archiepiscopal Museum, Ravenna. It is generally agreed that the throne was carved in the Greek East of the Byzantine Empire and shipped to Ravenna, but there has long been scholarly debate over whether it was made in Constantinople or Alexandria.

The Brescia Casket, also called the lipsanotheca of Brescia or reliquary of Brescia, is an ivory box, perhaps a reliquary, from the late 4th century, which is now in the Museo di Santa Giulia at San Salvatore in Brescia, Italy. It is a virtually unique survival of a complete Early Christian ivory box in generally good condition. The 36 subjects depicted on the box represent a wide range of the images found in the evolving Christian art of the period, and their identification has generated a great deal of art-historical discussion, though the high quality of the carving has never been in question. According to one scholar: "despite an abundance of resourceful and often astute exegesis, its date, use, provenance, and meaning remain among the most formidable and enduring enigmas in the study of early Christian art."

The Pyxis of Zamora is an carved ivory casket (pyx) that dates from the Caliphate of Córdoba. It is now in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain in Madrid, Spain.

The Troyes Casket is a carved ivory box of Byzantine origin. It is housed in the treasury of the Troyes Cathedral in Troyes, France.

The Salerno Ivories are a collection of Biblical ivory plaques from around the 11th or 12th century that contain elements of Early Christian, Byzantine, and Islamic art as well as influences from Western Romanesque and Anglo-Saxon art. Disputed in number, it is said there are between 38 and 70 plaques that comprise the collection. It is the largest unified set of ivory carvings preserved from the pre-Gothic Middle Ages, and depicts narrative scenes from both the Old and New Testaments. Some researchers believe the Ivories hold political significance and serve as commentary on the Investiture Controversy through their iconographies. The majority of the plaques are housed in the Diocesan Museum of the Cathedral of Salerno, which is where the group's main namesake comes from. It is supposed the ivories originated in either Salerno and Amalfi, which both contain identified ivory workshops, however neither has been definitively linked to the plaques so the city of origin remains unknown. Smaller groups of the plaques and fragments of panels are currently housed in different museum collections in Europe and America, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Louvre in Paris, the Museum of Fine Arts in Budapest, the Hamburg Museum of Art and Trade, and the Sculpture Collection in the Berlin State Museums.

Ivory carving is one of the traditional industries of Sri Lanka. The country's ivory carving industry has a very long history, but its origin is not yet fully understood. During the Kingdom of Kandy, ivory art became very popular and reached at its zenith. These delicate ivory works represent how Sri Lankan craftsmen mastered in this technique.

The Embriachi workshop was an important producer of objects in carved ivory and carved bone, set in a framework of inlaid wood, in north Italy from around 1375 to perhaps as late as 1433, apparently moving from Florence to Venice about 1395. They are especially known for what are now called marriage caskets or wedding caskets, hexagonal or oblong caskets about a foot across, with lids that rise up in the centre. Their output of these was probably made for stock rather than individual commissions, and filled a market for gifts for betrothals and weddings. They sold mirrors framed in a similar style, though fewer of these have survived, and religious pieces both small and in a few cases very large.