Mars, the fourth planet from the Sun, has appeared as a setting in works of fiction since at least the mid-1600s. Trends in the planet's portrayal have largely been influenced by advances in planetary science. It became the most popular celestial object in fiction in the late 1800s, when it became clear that there was no life on the Moon. The predominant genre depicting Mars at the time was utopian fiction. Around the same time, the mistaken belief that there are canals on Mars emerged and made its way into fiction, popularized by Percival Lowell's speculations of an ancient civilization having constructed them. The War of the Worlds, H. G. Wells's novel about an alien invasion of Earth by sinister Martians, was published in 1897 and went on to have a major influence on the science fiction genre.

Science fiction is a genre of speculative fiction, which typically deals with imaginative and futuristic concepts such as advanced science and technology, space exploration, time travel, parallel universes, and extraterrestrial life. It is related to fantasy, horror, and superhero fiction and contains many subgenres. Its exact definition has long been disputed among authors, critics, scholars, and readers.

An overwhelming majority of fiction is set on or features the Earth, as the only planet home to humans. This also holds true of science fiction, despite perceptions to the contrary. Works that focus specifically on Earth may do so holistically, treating the planet as one semi-biological entity. Counterfactual depictions of the shape of the Earth, be it flat or hollow, are occasionally featured. A personified, living Earth appears in a handful of works. In works set in the far future, Earth can be a center of space-faring human civilization, or just one of many inhabited planets of a galactic empire, and sometimes destroyed by ecological disaster or nuclear war or otherwise forgotten or lost.

An extraterrestrial or alien is any extraterrestrial lifeform: a lifeform that did not originate on Earth. The word extraterrestrial means "outside Earth". The first published use of extraterrestrial as a noun occurred in 1956, during the Golden Age of Science Fiction.

Adventure fiction is a type of fiction that usually presents danger, or gives the reader a sense of excitement. Some adventure fiction also satisfies the literary definition of romance fiction.

The literary genre of science fiction is diverse, and its exact definition remains a contested question among both scholars and devotees. This lack of consensus is reflected in debates about the genre's history, particularly over determining its exact origins. There are two broad camps of thought, one that identifies the genre's roots in early fantastical works such as the Sumerian Epic of Gilgamesh. A second approach argues that science fiction only became possible sometime between the 17th and early 19th centuries, following the scientific revolution and major discoveries in astronomy, physics, and mathematics.

Jupiter, the largest planet in the Solar System, has appeared in works of fiction across several centuries. The way the planet has been depicted has evolved as more has become known about its composition; it was initially portrayed as being entirely solid, later as having a high-pressure atmosphere with a solid surface underneath, and finally as being entirely gaseous. It was a popular setting during the pulp era of science fiction. Life on the planet has variously been depicted as identical to humans, larger versions of humans, and non-human. Non-human life on Jupiter has been portrayed as primitive in some works and more advanced than humans in others.

Neptune has appeared in fiction since shortly after its 1846 discovery, albeit infrequently. It initially made appearances indirectly—e.g. through its inhabitants—rather than as a setting. The earliest stories set on Neptune itself portrayed it as a rocky planet rather than as having its actual gaseous composition; later works rectified this error. Extraterrestrial life on Neptune is uncommon in fiction, though the exceptions have ranged from humanoids to gaseous lifeforms. Neptune's largest moon Triton has also appeared in fiction, especially in the late 20th century onwards.

The fictional portrayal of the Solar System has often included planets, moons, and other celestial objects which do not actually exist. Some of these objects were, at one time, seriously considered as hypothetical planets which were either thought to have been observed, or were hypothesized to be orbiting the Sun in order to explain certain celestial phenomena. Often such objects continued to be used in literature long after the hypotheses upon which they were based had been abandoned.

The concepts of space stations and space habitats feature in science fiction. The difference between the two is that habitats are larger and more complex structures intended as permanent homes for substantial populations, but the line between the two is fuzzy with significant overlap and the term space station is sometimes used for both concepts. The first such artificial satellite in fiction was Edward Everett Hale's "The Brick Moon" in 1869, a sphere of bricks 61 meters across accidentally launched into orbit around the Earth with people still onboard.

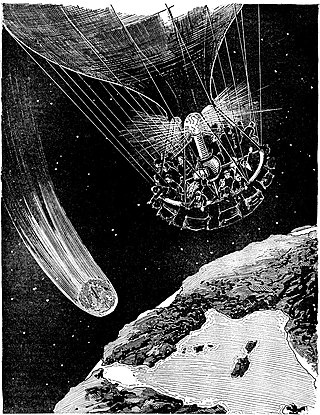

Comets have appeared in works of fiction since at least the 1830s. They primarily appear in science fiction as literal objects, but also make occasional symbolical appearances in other genres. In keeping with their traditional cultural associations as omens, they often threaten destruction to Earth. This commonly comes in the form of looming impact events, and occasionally through more novel means such as affecting Earth's atmosphere in different ways. In other stories, humans seek out and visit comets for purposes of research or resource extraction. Comets are inhabited by various forms of life ranging from microbes to vampires in different depictions, and are themselves living beings in some stories.

Gary Wesley Westfahl is an American writer and scholar of science fiction. He has written reviews for the Los Angeles Times, The Internet Review of Science Fiction and Locus Online. He worked at the University of California, Riverside until 2011 and is now an Professor Emeritus at the University of La Verne.

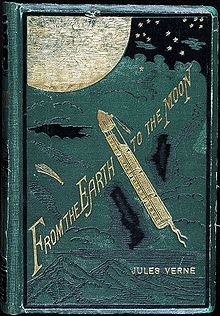

French science fiction is a substantial genre of French literature. It remains an active and productive genre which has evolved in conjunction with anglophone science fiction and other French and international literature.

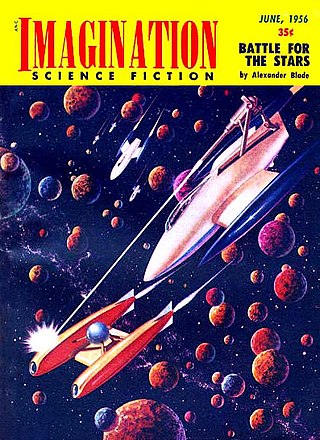

Space opera is a subgenre of science fiction that emphasizes space warfare, with use of melodramatic, risk-taking space adventures, relationships, and chivalric romance. Set mainly or entirely in outer space, it features technological and social advancements in faster-than-light travel, futuristic weapons, and sophisticated technology, on a backdrop of galactic empires and interstellar wars with fictional aliens, often in fictional galaxies. The term does not refer to opera music, but instead originally referred to the melodrama, scope, and formulaicness of operas, much as used in "horse opera", a 1930s phrase for a clichéd and formulaic Western film, and "soap opera", a melodramatic television series. Space operas emerged in the 1930s and continue to be produced in literature, film, comics, television, video games and board games.

The year 1889 was marked, in science fiction, by the following events.

The far future has been used as a setting in many works of science fiction. The far future setting arose in the late 19th century, as earlier writers had little understanding of concepts such as deep time and its implications for the nature of humankind. Classic examples of this genre include works such as H.G. Wells' The Time Machine (1895) or Olaf Stapledon's Last and First Men (1930). Recurring themes include themes such as Utopias, eschatology or the ultimate fate of the universe. Many works also overlap with other genres such as space opera, science fantasy or apocalyptic and post-apocalyptic fiction.

The Greenwood Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Themes, Works, and Wonders is an English language reference work on science fiction and fantasy, published in 2005 by Greenwood Press. It was edited by Gary Westfahl and consists of three volumes of 200 entries each. The first two volumes contain entries organized by themes, such as "Aliens in Space", "Asia" or "Rats and Mice", while the third volume lists works such as novels and films which are considered defining for the science fiction and fantasy genres.

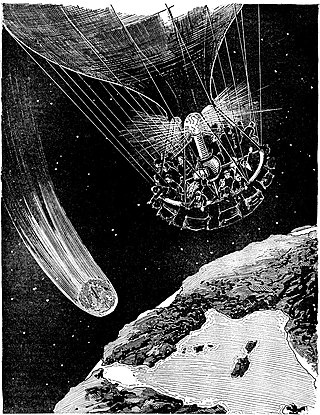

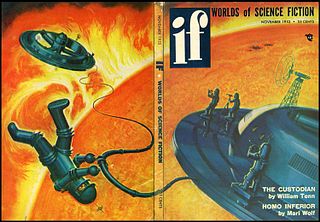

Space travel, or space flight is a classic science-fiction theme that has captivated the public and is almost archetypal for science fiction. Space travel, interplanetary or interstellar, is usually performed in space ships, and spacecraft propulsion in various works ranges from the scientifically plausible to the totally fictitious.

Technology in science fiction is a crucial aspect of the genre.

The Sun has appeared as a setting in fiction at least since classical antiquity, but for a long time it received relatively sporadic attention. Many of the early depictions viewed it as an essentially Earth-like and thus potentially habitable body—a once-common belief about celestial objects in general known as the plurality of worlds—and depicted various kinds of solar inhabitants. As more became known about the Sun through advances in astronomy, in particular its temperature, solar inhabitants fell out of favour save for the occasional more exotic alien lifeforms. Instead, many stories focused on the eventual death of the Sun and the havoc it would wreak upon life on Earth. Before it was understood that the Sun is powered by nuclear fusion, the prevailing assumption among writers was that combustion was the source of its heat and light, and it was expected to run out of fuel relatively soon. Even after the true source of the Sun's energy was discovered in the 1920s, the dimming or extinction of the Sun remained a recurring theme in disaster stories, with occasional attempts at averting disaster by reigniting the Sun. Another common way for the Sun to cause destruction is by exploding, and other mechanisms such as solar flares also appear on occasion.