Reformed Christianity, also called Calvinism, is a major branch of Protestantism that began during the sixteenth-century Protestant Reformation, a schism in the Roman Catholic Church. Today, it is largely represented by the Continental Reformed, Presbyterian, Reformed Anglican, Congregationalist, and Reformed Baptist denominational families.

Karl Paul Reinhold Niebuhr (1892–1971) was an American Reformed theologian, ethicist, commentator on politics and public affairs, and professor at Union Theological Seminary for more than 30 years. Niebuhr was one of America's leading public intellectuals for several decades of the 20th century and received the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1964. A public theologian, he wrote and spoke frequently about the intersection of religion, politics, and public policy, with his most influential books including Moral Man and Immoral Society and The Nature and Destiny of Man.

Karl Barth was a Swiss Reformed theologian. Barth is best known for his commentary The Epistle to the Romans, his involvement in the Confessing Church, including his authorship of the Barmen Declaration, and especially his unfinished multi-volume theological summa the Church Dogmatics. Barth's influence expanded well beyond the academic realm to mainstream culture, leading him to be featured on the cover of Time on 20 April 1962.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Christian theology:

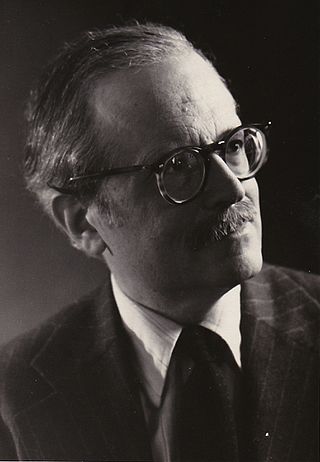

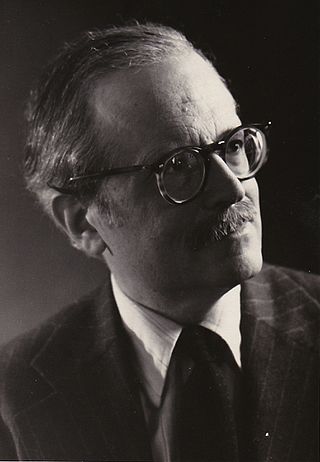

Paul Johannes Tillich was a German-American Christian existentialist philosopher, Christian socialist, and Lutheran theologian who was one of the most influential theologians of the twentieth century. Tillich taught at German universities before immigrating to the United States in 1933, where he taught at Union Theological Seminary, Harvard University, and the University of Chicago.

Systematic theology, or systematics, is a discipline of Christian theology that formulates an orderly, rational, and coherent account of the doctrines of the Christian faith. It addresses issues such as what the Bible teaches about certain topics or what is true about God and his universe. It also builds on biblical disciplines, church history, as well as biblical and historical theology. Systematic theology shares its systematic tasks with other disciplines such as constructive theology, dogmatics, ethics, apologetics, and philosophy of religion.

Karl Löwith was a German philosopher in the phenomenological tradition. A student of Husserl and Heidegger, he was one of the most prolific German philosophers of the twentieth century.

Christian existentialism is a theo-philosophical movement which takes an existentialist approach to Christian theology. The school of thought is often traced back to the work of the Danish philosopher and theologian Søren Kierkegaard (1813–1855) who is widely regarded as the father of existentialism.

Liberal Christianity, also known as liberal theology and historically as Christian Modernism, is a movement that interprets Christian teaching by taking into consideration modern knowledge, science and ethics. It emphasizes the importance of reason and experience over doctrinal authority. Liberal Christians view their theology as an alternative to both atheistic rationalism and theologies based on traditional interpretations of external authority, such as the Bible or sacred tradition.

Thomas Clark Oden (1931–2016) was an American Methodist theologian and religious author. He is often regarded as the father of the paleo-orthodox theological movement and is considered to be one of the most influential theologians of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century. He was Henry Anson Buttz Professor of Theology and Ethics at Drew University in New Jersey from 1980 until his retirement in 2004.

Postliberal theology is a Christian theological movement that focuses on a narrative presentation of the Christian faith as regulative for the development of a coherent systematic theology. Thus, Christianity is an overarching story, with its own embedded culture, grammar, and practices, which can be understood only with reference to Christianity's own internal logic.

Helmut Richard Niebuhr is considered one of the most important Christian theological ethicists in 20th-century America, best known for his 1951 book Christ and Culture and his posthumously published book The Responsible Self. The younger brother of theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, Richard Niebuhr taught for several decades at the Yale Divinity School. Both brothers were, in their day, important figures in the neo-orthodox theological school within American Protestantism. His theology has been one of the main sources of postliberal theology, sometimes called the "Yale school". He influenced such figures as James Gustafson, Stanley Hauerwas, and Gordon Kaufman.

Wolfhart Pannenberg was a German Lutheran theologian. He made a number of significant contributions to modern theology, including his concept of history as a form of revelation centered on the resurrection of Christ, which has been widely debated in both Protestant and Catholic theology, as well as by non-Christian thinkers.

Langdon Brown Gilkey was an American Protestant ecumenical theologian.

Heinrich Emil Brunner (1889–1966) was a Swiss Reformed theologian. Along with Karl Barth, he is commonly associated with neo-orthodoxy or the dialectical theology movement.

Edward John Carnell was a prominent Christian theologian and apologist, was an ordained Baptist pastor, and served as President of Fuller Theological Seminary in Pasadena, California. He was the author of nine major books, several of which attempted to develop a fresh outlook in Christian apologetics. He also wrote essays that were published in several other books, and was a contributor of articles to periodicals such as The Christian Century and Christianity Today.

Conservative Christianity, also known as conservative theology, theological conservatism, traditional Christianity, or biblical orthodoxy is a grouping of overlapping and denominationally diverse theological movements within Christianity that seeks to retain the orthodox and long-standing traditions and beliefs of Christianity. It is contrasted with Liberal Christianity and Progressive Christianity, which are seen as heretical heterodoxies by theological conservatives. Conservative Christianity should not be mistaken as being necessarily synonymous with the political philosophy of conservatism, nor the Christian right.

Karl Barth's views on Mary agreed with much Roman Catholic dogma but disagreed with the Catholic veneration of Mary. Barth, a leading 20th-century theologian, was a Reformed Protestant. Aware of the common dogmatic tradition of the early Church, Barth fully accepted the dogma of Mary as the Mother of God. Through Mary, Jesus belongs to the human race. Through Jesus, Mary is Mother of God.

Michael Wyschogrod was a Jewish German-American philosopher of religion, Jewish theologian, and activist for Jewish–Christian interfaith dialogue. During his academic career he taught in philosophy and religion departments of several universities in the United States, Europe and Israel.

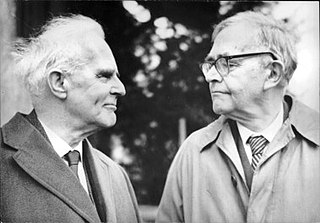

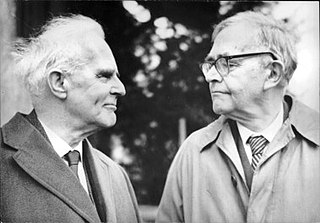

Wilhelm Pauck was a German-American church historian and historical theologian in the field of Reformation studies whose fifty-year teaching career reached from the University of Chicago and Union Theological Seminary, to Vanderbilt and Stanford universities. His impact was extended through frequent lectures and visiting appointments in the U.S. and Europe. Pauck served as a bridge between the historical-critical study of Protestant theology at the University of Berlin and U.S. universities, seminaries, and divinity schools. Combining high critical acumen with a keen sense of the drama of human history, in his prime Pauck was considered the Dean of historical theology in the United States. In the course of his career he became associated with Reinhold Niebuhr and Paul Tillich as friend, colleague, and confidant.