In philosophy, empiricism is an epistemological view that holds that true knowledge or justification comes only or primarily from sensory experience. It is one of several competing views within epistemology, along with rationalism and skepticism. Empiricism emphasizes the central role of empirical evidence in the formation of ideas, rather than innate ideas or traditions. However, empiricists may argue that traditions arise due to relations of previous sensory experiences.

Physics is a branch of science whose primary objects of study are matter and energy. Discoveries of physics find applications throughout the natural sciences and in technology. Physics today may be divided loosely into classical physics and modern physics.

Sir Isaac Newton was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author who was described in his time as a natural philosopher. He was a key figure in the Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment that followed. His pioneering book Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, first published in 1687, consolidated many previous results and established classical mechanics. Newton also made seminal contributions to optics, and shares credit with German mathematician Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz for developing infinitesimal calculus.

Science is a rigorous, systematic endeavor that builds and organizes knowledge in the form of testable explanations and predictions about the universe. Modern science is typically divided into three major branches: natural sciences, which study the physical world; the social sciences, which study individuals and societies; and the formal sciences, which study formal systems, governed by axioms and rules. There is disagreement whether the formal sciences are science disciplines, because they do not rely on empirical evidence. Applied sciences are disciplines that use scientific knowledge for practical purposes, such as in engineering and medicine.

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology and chemistry transformed the views of society about nature. The Scientific Revolution took place in Europe in the second half of the Renaissance period, with the 1543 Nicolaus Copernicus publication De revolutionibus orbium coelestium often cited as its beginning.

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment, also known as the Age of Reason, was an intellectual and philosophical movement that occurred in Europe, especially Western Europe, in the 17th and 18th centuries, with global influences and effects. The Enlightenment included a range of ideas centered on the value of human happiness, the pursuit of knowledge obtained by means of reason and the evidence of the senses, and ideals such as natural law, liberty, progress, toleration, fraternity, constitutional government, and separation of church and state.

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatability of findings are used to try to ensure the validity of scientific advances.

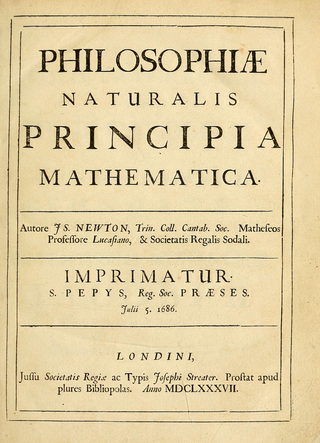

Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica often referred to as simply the Principia, is a book by Isaac Newton that expounds Newton's laws of motion and his law of universal gravitation. The Principia is written in Latin and comprises three volumes, and was first published on 5 July 1687.

In philosophy of science and in epistemology, instrumentalism is a methodological view that ideas are useful instruments, and that the worth of an idea is based on how effective it is in explaining and predicting natural phenomena. According to instrumentalists, a successful scientific theory reveals nothing known either true or false about nature's unobservable objects, properties or processes. Scientific theory is merely a tool whereby humans predict observations in a particular domain of nature by formulating laws, which state or summarize regularities, while theories themselves do not reveal supposedly hidden aspects of nature that somehow explain these laws. Instrumentalism is a perspective originally introduced by Pierre Duhem in 1906.

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

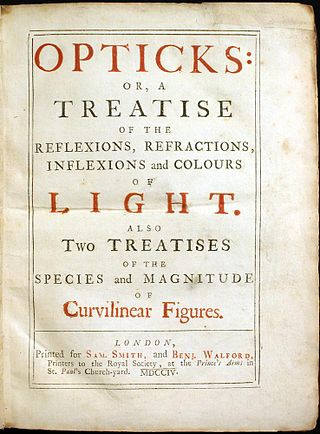

Opticks: or, A Treatise of the Reflexions, Refractions, Inflexions and Colours of Light is a book by English natural philosopher Isaac Newton that was published in English in 1704. The book analyzes the fundamental nature of light by means of the refraction of light with prisms and lenses, the diffraction of light by closely spaced sheets of glass, and the behaviour of color mixtures with spectral lights or pigment powders. Opticks was Newton's second major book on physical science and it is considered one of the three major works on optics during the Scientific Revolution. Newton's name did not appear on the title page of the first edition of Opticks.

Early modern philosophy is a period in the history of philosophy that overlaps with the beginning of the period known as modern philosophy.

Gabrielle Émilie Le Tonnelier de Breteuil, Marquise du Châtelet was a French natural philosopher and mathematician from the early 1730s until her death due to complications during childbirth in 1749.

In optics, the corpuscular theory of light states that light is made up of small discrete particles called "corpuscles" which travel in a straight line with a finite velocity and possess impetus. This was based on an alternate description of atomism of the time period.

The history of scientific method considers changes in the methodology of scientific inquiry, as distinct from the history of science itself. The development of rules for scientific reasoning has not been straightforward; scientific method has been the subject of intense and recurring debate throughout the history of science, and eminent natural philosophers and scientists have argued for the primacy of one or another approach to establishing scientific knowledge.

Inductivism is the traditional and still commonplace philosophy of scientific method to develop scientific theories. Inductivism aims to neutrally observe a domain, infer laws from examined cases—hence, inductive reasoning—and thus objectively discover the sole naturally true theory of the observed.

The "General Scholium" is an essay written by Isaac Newton, appended to his work of Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica, known as the Principia. It was first published with the second (1713) edition of the Principia and reappeared with some additions and modifications on the third (1726) edition. It is best known for the "Hypotheses non fingo" expression, which Newton used as a response to some of the criticism received after the release of the first edition (1687). In the essay Newton not only counters the natural philosophy of René Descartes and Gottfried Leibniz, but also addresses issues of scientific methodology, theology, and metaphysics.

The history of science during the Age of Enlightenment traces developments in science and technology during the Age of Reason, when Enlightenment ideas and ideals were being disseminated across Europe and North America. Generally, the period spans from the final days of the 16th and 17th-century Scientific Revolution until roughly the 19th century, after the French Revolution (1789) and the Napoleonic era (1799–1815). The scientific revolution saw the creation of the first scientific societies, the rise of Copernicanism, and the displacement of Aristotelian natural philosophy and Galen's ancient medical doctrine. By the 18th century, scientific authority began to displace religious authority, and the disciplines of alchemy and astrology lost scientific credibility.

An index list of articles about the philosophy of science.

Deism, the religious attitude typical of the Enlightenment, especially in France and England, holds that the only way the existence of God can be proven is to combine the application of reason with observation of the world. A Deist is defined as "One who believes in the existence of a God or Supreme Being but denies revealed religion, basing his belief on the light of nature and reason." Deism was often synonymous with so-called natural religion because its principles are drawn from nature and human reasoning. In contrast to Deism there are many cultural religions or revealed religions, such as Judaism, Trinitarian Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, and others, which believe in supernatural intervention of God in the world; while Deism denies any supernatural intervention and emphasizes that the world is operated by natural laws of the Supreme Being.