Bra–ket notation, also called Dirac notation, is a notation for linear algebra and linear operators on complex vector spaces together with their dual space both in the finite-dimensional and infinite-dimensional case. It is specifically designed to ease the types of calculations that frequently come up in quantum mechanics. Its use in quantum mechanics is quite widespread.

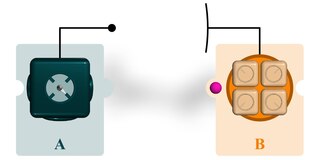

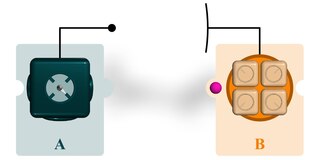

Quantum teleportation is a technique for transferring quantum information from a sender at one location to a receiver some distance away. While teleportation is commonly portrayed in science fiction as a means to transfer physical objects from one location to the next, quantum teleportation only transfers quantum information. The sender does not have to know the particular quantum state being transferred. Moreover, the location of the recipient can be unknown, but to complete the quantum teleportation, classical information needs to be sent from sender to receiver. Because classical information needs to be sent, quantum teleportation cannot occur faster than the speed of light.

Quantum entanglement is the phenomenon of a group of particles being generated, interacting, or sharing spatial proximity in such a way that the quantum state of each particle of the group cannot be described independently of the state of the others, including when the particles are separated by a large distance. The topic of quantum entanglement is at the heart of the disparity between classical and quantum physics: entanglement is a primary feature of quantum mechanics not present in classical mechanics.

Quantum decoherence is the loss of quantum coherence, the process in which a system's behaviour changes from that which can be explained by quantum mechanics to that which can be explained by classical mechanics. Beginning out of attempts to extend the understanding of quantum mechanics, the theory has developed in several directions and experimental studies have confirmed some of the key issues. Quantum computing relies on quantum coherence and is the primary practical applications of the concept.

In quantum information theory, a quantum channel is a communication channel which can transmit quantum information, as well as classical information. An example of quantum information is the state of a qubit. An example of classical information is a text document transmitted over the Internet.

LOCC, or local operations and classical communication, is a method in quantum information theory where a local (product) operation is performed on part of the system, and where the result of that operation is "communicated" classically to another part where usually another local operation is performed conditioned on the information received.

Wigner's theorem, proved by Eugene Wigner in 1931, is a cornerstone of the mathematical formulation of quantum mechanics. The theorem specifies how physical symmetries such as rotations, translations, and CPT transformations are represented on the Hilbert space of states.

In functional analysis and quantum information science, a positive operator-valued measure (POVM) is a measure whose values are positive semi-definite operators on a Hilbert space. POVMs are a generalization of projection-valued measures (PVM) and, correspondingly, quantum measurements described by POVMs are a generalization of quantum measurement described by PVMs.

In physics, in the area of quantum information theory, a Greenberger–Horne–Zeilinger state is a certain type of entangled quantum state that involves at least three subsystems. The four-particle version was first studied by Daniel Greenberger, Michael Horne and Anton Zeilinger in 1989, and the three-particle version was introduced by N. David Mermin in 1990. Extremely non-classical properties of the state have been observed. GHZ states for large numbers of qubits are theorized to give enhanced performance for metrology compared to other qubit superposition states.

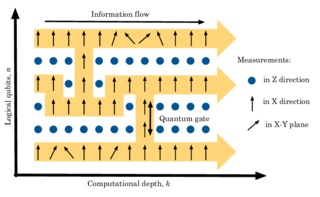

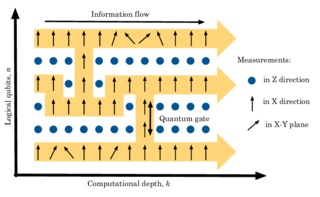

The one-way or measurement-based quantum computer (MBQC) is a method of quantum computing that first prepares an entangled resource state, usually a cluster state or graph state, then performs single qubit measurements on it. It is "one-way" because the resource state is destroyed by the measurements.

In physics, the no-deleting theorem of quantum information theory is a no-go theorem which states that, in general, given two copies of some arbitrary quantum state, it is impossible to delete one of the copies. It is a time-reversed dual to the no-cloning theorem, which states that arbitrary states cannot be copied. This theorem seems remarkable, because, in many senses, quantum states are fragile; the theorem asserts that, in a particular case, they are also robust. Physicist Arun K. Pati along with Samuel L. Braunstein proved this theorem.

A decoherence-free subspace (DFS) is a subspace of a quantum system's Hilbert space that is invariant to non-unitary dynamics. Alternatively stated, they are a small section of the system Hilbert space where the system is decoupled from the environment and thus its evolution is completely unitary. DFSs can also be characterized as a special class of quantum error correcting codes. In this representation they are passive error-preventing codes since these subspaces are encoded with information that (possibly) won't require any active stabilization methods. These subspaces prevent destructive environmental interactions by isolating quantum information. As such, they are an important subject in quantum computing, where (coherent) control of quantum systems is the desired goal. Decoherence creates problems in this regard by causing loss of coherence between the quantum states of a system and therefore the decay of their interference terms, thus leading to loss of information from the (open) quantum system to the surrounding environment. Since quantum computers cannot be isolated from their environment and information can be lost, the study of DFSs is important for the implementation of quantum computers into the real world.

Entanglement distillation is the transformation of N copies of an arbitrary entangled state into some number of approximately pure Bell pairs, using only local operations and classical communication.

In quantum mechanics, and especially quantum information theory, the purity of a normalized quantum state is a scalar defined as

In quantum mechanics, weak measurements are a type of quantum measurement that results in an observer obtaining very little information about the system on average, but also disturbs the state very little. From Busch's theorem the system is necessarily disturbed by the measurement. In the literature weak measurements are also known as unsharp, fuzzy, dull, noisy, approximate, and gentle measurements. Additionally weak measurements are often confused with the distinct but related concept of the weak value.

In quantum computation, the Hadamard test is a method used to create a random variable whose expected value is the expected real part , where is a quantum state and is a unitary gate acting on the space of . The Hadamard test produces a random variable whose image is in and whose expected value is exactly . It is possible to modify the circuit to produce a random variable whose expected value is by applying an gate after the first Hadamard gate.

The no-hiding theorem states that if information is lost from a system via decoherence, then it moves to the subspace of the environment and it cannot remain in the correlation between the system and the environment. This is a fundamental consequence of the linearity and unitarity of quantum mechanics. Thus, information is never lost. This has implications in black hole information paradox and in fact any process that tends to lose information completely. The no-hiding theorem is robust to imperfection in the physical process that seemingly destroys the original information.

In quantum information theory and quantum optics, the Schrödinger–HJW theorem is a result about the realization of a mixed state of a quantum system as an ensemble of pure quantum states and the relation between the corresponding purifications of the density operators. The theorem is named after physicists and mathematicians Erwin Schrödinger, Lane P. Hughston, Richard Jozsa and William Wootters. The result was also found independently by Nicolas Gisin, and by Nicolas Hadjisavvas building upon work by Ed Jaynes, while a significant part of it was likewise independently discovered by N. David Mermin. Thanks to its complicated history, it is also known by various other names such as the GHJW theorem, the HJW theorem, and the purification theorem.

In quantum physics, the "monogamy" of quantum entanglement refers to the fundamental property that it cannot be freely shared between arbitrarily many parties.

Bell diagonal states are a class of bipartite qubit states that are frequently used in quantum information and quantum computation theory.