Category theory is a general theory of mathematical structures and their relations that was introduced by Samuel Eilenberg and Saunders Mac Lane in the middle of the 20th century in their foundational work on algebraic topology. Category theory is used in almost all areas of mathematics. In particular, many constructions of new mathematical objects from previous ones that appear similarly in several contexts are conveniently expressed and unified in terms of categories. Examples include quotient spaces, direct products, completion, and duality.

In algebra, a homomorphism is a structure-preserving map between two algebraic structures of the same type. The word homomorphism comes from the Ancient Greek language: ὁμός meaning "same" and μορφή meaning "form" or "shape". However, the word was apparently introduced to mathematics due to a (mis)translation of German ähnlich meaning "similar" to ὁμός meaning "same". The term "homomorphism" appeared as early as 1892, when it was attributed to the German mathematician Felix Klein (1849–1925).

In mathematics, an abelian category is a category in which morphisms and objects can be added and in which kernels and cokernels exist and have desirable properties.

In mathematics, a category is a collection of "objects" that are linked by "arrows". A category has two basic properties: the ability to compose the arrows associatively and the existence of an identity arrow for each object. A simple example is the category of sets, whose objects are sets and whose arrows are functions.

In the context of abstract algebra or universal algebra, a monomorphism is an injective homomorphism. A monomorphism from X to Y is often denoted with the notation .

In category theory, an epimorphism is a morphism f : X → Y that is right-cancellative in the sense that, for all objects Z and all morphisms g1, g2: Y → Z,

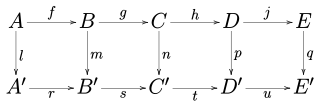

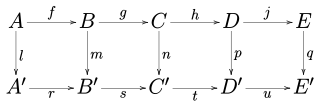

In mathematics, and especially in category theory, a commutative diagram is a diagram such that all directed paths in the diagram with the same start and endpoints lead to the same result. It is said that commutative diagrams play the role in category theory that equations play in algebra.

Homological algebra is the branch of mathematics that studies homology in a general algebraic setting. It is a relatively young discipline, whose origins can be traced to investigations in combinatorial topology and abstract algebra at the end of the 19th century, chiefly by Henri Poincaré and David Hilbert.

In category theory, a branch of mathematics, the opposite category or dual categoryCop of a given category C is formed by reversing the morphisms, i.e. interchanging the source and target of each morphism. Doing the reversal twice yields the original category, so the opposite of an opposite category is the original category itself. In symbols, .

In category theory, a branch of abstract mathematics, an equivalence of categories is a relation between two categories that establishes that these categories are "essentially the same". There are numerous examples of categorical equivalences from many areas of mathematics. Establishing an equivalence involves demonstrating strong similarities between the mathematical structures concerned. In some cases, these structures may appear to be unrelated at a superficial or intuitive level, making the notion fairly powerful: it creates the opportunity to "translate" theorems between different kinds of mathematical structures, knowing that the essential meaning of those theorems is preserved under the translation.

In category theory, a branch of mathematics, a subobject is, roughly speaking, an object that sits inside another object in the same category. The notion is a generalization of concepts such as subsets from set theory, subgroups from group theory, and subspaces from topology. Since the detailed structure of objects is immaterial in category theory, the definition of subobject relies on a morphism that describes how one object sits inside another, rather than relying on the use of elements.

This is a glossary of properties and concepts in category theory in mathematics.

In mathematics, particularly in homotopy theory, a model category is a category with distinguished classes of morphisms ('arrows') called 'weak equivalences', 'fibrations' and 'cofibrations' satisfying certain axioms relating them. These abstract from the category of topological spaces or of chain complexes. The concept was introduced by Daniel G. Quillen.

In category theory, the notion of a projective object generalizes the notion of a projective module. Projective objects in abelian categories are used in homological algebra. The dual notion of a projective object is that of an injective object.

In category theory, a regular category is a category with finite limits and coequalizers of a pair of morphisms called kernel pairs, satisfying certain exactness conditions. In that way, regular categories recapture many properties of abelian categories, like the existence of images, without requiring additivity. At the same time, regular categories provide a foundation for the study of a fragment of first-order logic, known as regular logic.

In category theory, a branch of mathematics, a section is a right inverse of some morphism. Dually, a retraction is a left inverse of some morphism. In other words, if and are morphisms whose composition is the identity morphism on , then is a section of , and is a retraction of .

In mathematics, specifically in category theory, an exact category is a category equipped with short exact sequences. The concept is due to Daniel Quillen and is designed to encapsulate the properties of short exact sequences in abelian categories without requiring that morphisms actually possess kernels and cokernels, which is necessary for the usual definition of such a sequence.

In category theory, the concept of an element, or a point, generalizes the more usual set theoretic concept of an element of a set to an object of any category. This idea often allows restating of definitions or properties of morphisms given by a universal property in more familiar terms, by stating their relation to elements. Some very general theorems, such as Yoneda's lemma and the Mitchell embedding theorem, are of great utility for this, by allowing one to work in a context where these translations are valid. This approach to category theory – in particular the use of the Yoneda lemma in this way – is due to Grothendieck, and is often called the method of the functor of points.

In mathematics, particularly in category theory, a morphism is a structure-preserving map from one mathematical structure to another one of the same type. The notion of morphism recurs in much of contemporary mathematics. In set theory, morphisms are functions; in linear algebra, linear transformations; in group theory, group homomorphisms; in analysis and topology, continuous functions, and so on.

In category theory, an abstract mathematical discipline, a nodal decomposition of a morphism is a representation of as a product , where is a strong epimorphism, a bimorphism, and a strong monomorphism.