Related Research Articles

Aulus Gellius was a Roman author and grammarian, who was probably born and certainly brought up in Rome. He was educated in Athens, after which he returned to Rome. He is famous for his Attic Nights, a commonplace book, or compilation of notes on grammar, philosophy, history, antiquarianism, and other subjects, preserving fragments of the works of many authors who might otherwise be unknown today.

Classical Latin is the form of Literary Latin recognized as a literary standard by writers of the late Roman Republic and early Roman Empire. It was used from 75 BC to the 3rd century AD, when it developed into Late Latin. In some later periods, it was regarded as good or proper Latin, with following versions viewed as debased, degenerate, or corrupted. The word Latin is now understood by default to mean "Classical Latin"; for example, modern Latin textbooks almost exclusively teach Classical Latin.

Alexander Numenius, or Alexander, son of Numenius, was a Greek rhetorician who flourished in the first half of the 2nd century. About his life almost nothing is known. We possess two works ascribed to him. The one which certainly is his work bears the title Περὶ τῶν τῆς διανοίας καὶ τῆς λέξεως σχημάτων Peri ton tes dianoias kai tes lexeos schematon. Julius Rufinianus, in his work on the same subject expressly states that Aquila Romanus, in his Latin treatise De Figuris Sententiarum et Elocutionis, took his materials from Alexander's work. Another epitome was made in the 4th century by a Christian for use in Christian schools, containing additional examples from Gregory Nazianzus.

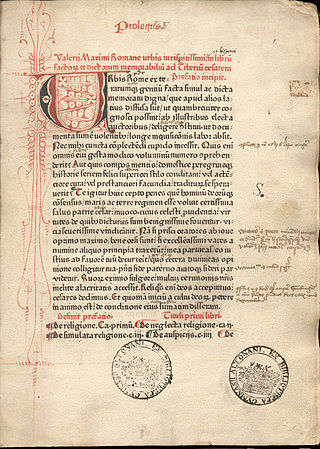

Valerius Maximus was a 1st-century Latin writer and author of a collection of historical anecdotes: Factorum et dictorum memorabilium libri IX. He worked during the reign of Tiberius.

Lucian Müller was a German classical scholar.

The Carmen Arvale is the preserved chant of the Arval priests or Fratres Arvales of ancient Rome.

Gnaeus Naevius was a Roman epic poet and dramatist of the Old Latin period. He had a notable literary career at Rome until his satiric comments delivered in comedy angered the Metellus family, one of whom was consul. After a sojourn in prison he recanted and was set free by the tribunes. After a second offense he was exiled to Tunisia, where he wrote his own epitaph and committed suicide. His comedies were in the genre of Palliata Comoedia, an adaptation of Greek New Comedy. A soldier in the Punic Wars, he was highly patriotic, inventing a new genre called Praetextae Fabulae, an extension of tragedy to Roman national figures or incidents, named after the Toga praetexta worn by high officials. Of his writings there survive only fragments of several poems preserved in the citations of late ancient grammarians.

Late Latin is the scholarly name for the form of Literary Latin of late antiquity. English dictionary definitions of Late Latin date this period from the 3rd to the 6th centuries CE, and continuing into the 7th century in the Iberian Peninsula. This somewhat ambiguously defined version of Latin was used between the eras of Classical Latin and Medieval Latin. Scholars do not agree exactly when Classical Latin should end or Medieval Latin should begin.

Sextus Pompeius Festus, usually known simply as Festus, was a Roman grammarian who probably flourished in the later 2nd century AD, perhaps at Narbo (Narbonne) in Gaul.

Marcellus Empiricus, also known as Marcellus Burdigalensis, was a Latin medical writer from Gaul at the turn of the 4th and 5th centuries. His only extant work is the De medicamentis, a compendium of pharmacological preparations drawing on the work of multiple medical and scientific writers as well as on folk remedies and magic. It is a significant if quirky text in the history of European medical writing, an infrequent subject of monographs, but regularly mined as a source for magic charms, Celtic herbology and lore, and the linguistic study of Gaulish and Vulgar Latin. Bonus auctor est was the judgment of J.J. Scaliger, while the science historian George Sarton called the De medicamentis an “extraordinary mixture of traditional knowledge, popular (Celtic) medicine, and rank superstition.” Marcellus is usually identified with the magister officiorum of that name who held office during the reign of Theodosius I.

Siburius, for whom only the single name survives, was a high-ranking official of the Roman Empire. He was one of several Gauls who rose to political prominence in the late 4th century as a result of the emperor Gratian's appointment of his Bordelaise tutor Ausonius to high office.

Wallace Martin Lindsay was a classical scholar of the late 19th and early 20th centuries and a palaeographer. He was Professor of Humanity at University of St Andrews.

In ancient Roman religion, the indigitamenta were lists of deities kept by the College of Pontiffs to assure that the correct divine names were invoked for public prayers. These lists or books probably described the nature of the various deities who might be called on under particular circumstances, with specifics about the sequence of invocation. The earliest indigitamenta, like many other aspects of Roman religion, were attributed to Numa Pompilius, second king of Rome.

Hortensius or On Philosophy is a lost dialogue written by Marcus Tullius Cicero in the year 45 BC. The dialogue—which is named after Cicero's friendly rival and associate, the speaker and politician Quintus Hortensius Hortalus—took the form of a protreptic. In the work, Cicero, Hortensius, Quintus Lutatius Catulus, and Lucius Licinius Lucullus discuss the best use of one's leisure time. At the conclusion of the work, Cicero argues that the pursuit of philosophy is the most important endeavor.

The secespita is a long iron sacrificial knife, made of brass and copper from Cyprus, with a solid and rounded ivory handle, which is secured to the hilt by a ring of silver or gold. The flamens and their wives, the flaminicae, who were priests and priestesses of the Ancient Rome, the virgins and the pontiffs made use of it for sacrifices. This knife derives its name from the Latin verb seco.

Georgius Lauer was a German printer who worked in Rome in the late fifteenth century, responsible for important publications by classical authors and renaissance humanists, including editiones principes by Festus, Nonius, Varro, Poggio Bracciolini, and others, as well as patristic writers such as John Chrysostom.

De verborum significatione libri XX, also known as the Lexicon of Festus, is an epitome compiled, edited, and annotated by Sextus Pompeius Festus from the encyclopedic works of Verrius Flaccus. Festus' epitome is typically dated to the 2nd century, but the work only survives in an incomplete 11th-century manuscript and copies of its own separate epitome.

Annales is the name of a fragmentary Latin epic poem written by the Roman poet Ennius in the 2nd century BC. While only snippets of the work survive today, the poem's influence on Latin literature was significant. Although written in Latin, stylistically it borrows from the Greek poetic tradition, particularly the works of Homer, and is written in dactylic hexameter. The poem was significantly larger than others from the period, and eventually comprised 18 books.

The gens Nonia was a plebeian family at ancient Rome. Its members first appear in history toward the end of the Republic. The first of the Nonii to obtain the consulship was Lucius Nonius Asprenas in 36 BC. From then until the end of the fourth century, they regularly held the highest offices of the Roman state.

Ralph of Beauvais was an English grammarian and linguist.

References

- ↑ Matthew Bunson, A Dictionary of the Roman Empire (Oxford University Press, 1995), p. 258.

- ↑ CIL VIII 4878; W. M. Lindsay, Noni Marcelli, vol. 1, Teubner, 1903, p. xiii.

- ↑ H. Nettleship, American Journal of Philology Vol. 3, No. 9 (1882), pp. 1-16. pp. 2–3: "His assumption of the title Peripateticus justifies us in concluding further that he was not a Christian; the contents of his book prove that he was an eager student of ancient and classical Latin. He may fairly therefore be classed, for literary purposes, among the non-Christian scholars and antiquarians of the fourth and fifth centuries; with Servius the commentator on Vergil, Macrobius, and the elder Symmachus."

- ↑ W. M. Lindsay, Noni Marcelli, vol. 1, Teubner, 1903, p. xiii. Note 2 lists references to Nonius by Priscian in Inst. I, p. 35; I. p. 269 and 499.

- ↑ Robert Browning, "Grammarians," in the Cambridge History of Classical Literature, vol. 2: Latin Literature, 1982, p. 769.

- ↑ W. M. Lindsay, Nonius Marcellus, St. Andrews University Publications 1, Oxford: Parker (1901), p. 1.

- ↑ Paul T. Keyser, Late Authors in Nonius Marcellus and Other Evidence of His Date, Harvard Studies in Classical Philology, Vol. 96 (1994), pp. 369–389. pp. 388–9: "The prevailing belief that Nonius must belong roughly to the fourth century A.D. is based on little more than the tendency to presume that an undatable Latin work associated with a Roman aristocrat dates from the fourth century A.D. ... The inference that Nonius is Severan is ... based on ... the otherwise isolated and inexplicable cluster of quotations of authors dated to ca. A.D. 160-210 in the context of Nonius' express preference for the auctoritas of Republican and Augustan authors. Furthermore, this is supported by some items of contemporary language he records, by his heavy use of rolls rather than codices, and by his designation as a Peripatetic. In the end, one can conclude that he is to be dated to ca. A.D. 205–20."

- ↑ W. M. Lindsay, Nonius Marcellus, St. Andrews University Publications 1, Oxford: Parker (1901), p. 1.

- ↑ Browning, Cambridge History of Classical Literature, vol. 2: Latin Literature, p. 769.

- ↑ Nonius Marcellus' Dictionary of Republican Latin, 1901. Reference from Habinek.

- ↑ Paulys Real-Encyclopadie 33.882-97. Reference from Habinek.

- ↑ Thomas N. Habinek, The colometry of Latin prose (1985), pp. 115–6. Preview here.

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica entry.

- ↑ George Crabb (1833), Universal historical dictionary, volume 2, no page numbers, online here: "NONIUS, Marcellus, (Biog.) a grammarian and peripatetic philosopher and a native of Tibur, whose treatise, 'De varia significatione verborum' was edited by Mercer, 8vo, Paris, 1614."

- ↑ W. M. Lindsay, Nonius Marcellus, St. Andrews University Publications 1, Oxford: Parker (1901), p. 1: "He published a volume of letters 'On the Neglect of Study,' from which he quotes a pompous sentence in illustration of the word meridies (p. 451 of Mercier's edition)."