The Snowy Mountains scheme or Snowy scheme is a hydroelectricity and irrigation complex in south-east Australia. The Scheme consists of sixteen major dams; nine power stations; two pumping stations; and 225 kilometres (140 mi) of tunnels, pipelines and aqueducts that were constructed between 1949 and 1974. The Scheme was completed under the supervision of Chief Engineer, Sir William Hudson. It is the largest engineering project undertaken in Australia.

The South Saskatchewan River is a major river in Canada that flows through the provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan.

Glen Canyon Dam is a concrete arch-gravity dam on the Colorado River in northern Arizona, United States, near the town of Page. The 710-foot (220 m) high dam was built by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation (USBR) from 1956 to 1966 and forms Lake Powell, one of the largest man-made reservoirs in the U.S. with a capacity of 27 million acre feet (33 km3). The dam is named for Glen Canyon, a series of deep sandstone gorges now flooded by the reservoir; Lake Powell is named for John Wesley Powell, who in 1869 led the first expedition to traverse the Colorado's Grand Canyon by boat.

The California water wars were a series of political conflicts between the city of Los Angeles and farmers and ranchers in the Owens Valley of Eastern California over water rights.

The Teton Dam was an earthen dam on the Teton River in Idaho, United States. It was built by the Bureau of Reclamation, one of eight federal agencies authorized to construct dams. Located in the eastern part of the state, between Fremont and Madison counties, it suffered a catastrophic failure on June 5, 1976, as it was filling for the first time.

Cadillac Desert (1986), is a history by American Marc Reisner about land development and water policy in the western United States. Subtitled The American West and its Disappearing Water, it explores the history of the federal agencies, Bureau of Reclamation and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and their struggles to remake the American West in ways to satisfy national settlement goals. The book concludes that the development-driven policies, formed when settling the West was the country's main concern, have had serious long-term negative effects on the environment and water quantity. The book was revised and updated in 1993.

The Bow River is a river in Alberta, Canada. It begins within the Canadian Rocky Mountains and winds through the Alberta foothills onto the prairies, where it meets the Oldman River, the two then forming the South Saskatchewan River. These waters ultimately flow through the Nelson River into Hudson Bay. The Bow River runs through the city of Calgary, taking in the Elbow River at the historic site of Fort Calgary near downtown. The Bow River pathway, developed along the river's banks, is considered a part of Calgary's self-image.

The Columbia Basin Project in Central Washington, United States, is the irrigation network that the Grand Coulee Dam makes possible. It is the largest water reclamation project in the United States, supplying irrigation water to over 670,000 acres (2,700 km2) of the 1,100,000 acres (4,500 km2) large project area, all of which was originally intended to be supplied and is still classified as irrigable and open for the possible enlargement of the system. Water pumped from the Columbia River is carried over 331 miles (533 km) of main canals, stored in a number of reservoirs, then fed into 1,339 miles (2,155 km) of lateral irrigation canals, and out into 3,500 miles (5,600 km) of drains and wasteways. The Grand Coulee Dam, powerplant, and various other parts of the CBP are operated by the Bureau of Reclamation. There are three irrigation districts in the project area, which operate additional local facilities.

Grand Lake is Colorado's largest and deepest natural lake. It is located in the headwaters of the Colorado River in Grand County, Colorado. On its north shore is located the historic and eponymous town of Grand Lake. The lake was formed during the Pinedale glaciation, which occurred from 30000 BP to 10000 BP. The glacial terminal moraine created a natural dam. Natural tributaries to the lake are the North Inlet and East Inlet, both of which flow out of Rocky Mountain National Park, which surrounds the lake on three sides. Grand Lake is located 1 mile from the Park's western entrance. Grand Lake was named Spirit Lake by the Ute Tribe because they believed the lake's cold waters to be the dwelling place of departed souls.

The California State Water Project, commonly known as the SWP, is a state water management project in the U.S. state of California under the supervision of the California Department of Water Resources. The SWP is one of the largest public water and power utilities in the world, providing drinking water for more than 23 million people and generating an average of 6,500 GWh of hydroelectricity annually. However, as it is the largest single consumer of power in the state itself, it has a net usage of 5,100 GWh.

The Robert Moses Niagara Hydroelectric Power Station is a hydroelectric power station in Lewiston, New York, near Niagara Falls. Owned and operated by the New York Power Authority (NYPA), the plant diverts water from the Niagara River above Niagara Falls and returns the water into the lower portion of the river near Lake Ontario. It uses 13 generators at an installed capacity of 2,675 MW (3,587,000 hp).

The Brazeau River is a river in western Alberta, Canada. It is a major tributary of the North Saskatchewan River.

Lake Qaraoun is an artificial lake or reservoir located in the southern region of the Beqaa Valley, Lebanon. It was created near Qaraoun village in 1959 by building a 61 m-high (200 ft) concrete-faced rockfill dam in the middle reaches of the Litani River. The reservoir has been used for hydropower generation, domestic water supply, and for irrigation of 27,500 ha.

The Kenney Dam is a rock-fill embankment dam on the Nechako River in northwestern British Columbia, built in the early 1950s. The impoundment of water behind the dam forms the Nechako Reservoir, which is also commonly known as the Ootsa Lake Reservoir. The dam was constructed to power an aluminum smelter in Kitimat, British Columbia by Alcan, although in the late 1980s the company increased their economic activity by selling excess electricity across North America. The development of the dam caused various environmental problems along with the displacement of the Cheslatta T'En First Nation, whose traditional land was flooded.

The Central Utah Project is a US federal water project that was authorized for construction under the Colorado River Storage Project Act of April 11, 1956, as a participating project. In general, the Central Utah Project develops a portion of Utah's share of the yield of the Colorado River, as set out in the Colorado River Compact of 1922.

Interbasin transfer or transbasin diversion are terms used to describe man-made conveyance schemes which move water from one river basin where it is available, to another basin where water is less available or could be utilized better for human development. The purpose of such designed schemes can be to alleviate water shortages in the receiving basin, to generate electricity, or both. Rarely, as in the case of the Glory River which diverted water from the Tigris to Euphrates River in modern Iraq, interbasin transfers have been undertaken for political purposes. While ancient water supply examples exist, the first modern developments were undertaken in the 19th century in Australia, India and the United States; large cities such as Denver and Los Angeles would not exist as we know them today without these diversion transfers. Since the 20th century many more similar projects have followed in other countries, including Israel, Canada and China. Utilized alternatively, the Green Revolution in India and hydropower development in Canada could not have been accomplished without such man-made transfers.

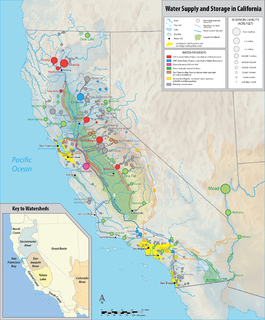

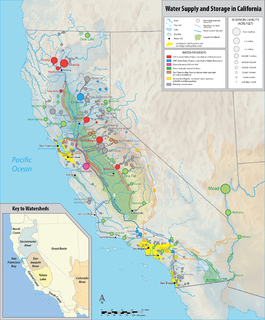

California's interconnected water system serves over 30 million people and irrigates over 5,680,000 acres (2,300,000 ha) of farmland. As the world's largest, most productive, and potentially most controversial water system, it manages over 40 million acre feet (49 km3) of water per year.

The Klamath Diversion was a federal water project proposed by the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation in the 1950s. It would have diverted the Klamath River in Northern California to the more arid central and southern parts of that state. It would relieve irrigation water demand and groundwater overdraft in the Central Valley and boost the water supply for Southern California. Through the latter it would allow for other Southwestern states—Arizona, Nevada, New Mexico and Utah—as well as Mexico to receive an increased share of the waters of the Colorado River.

Hooker Dam was a proposed dam on the Gila River in New Mexico, planned as a major component of the Central Arizona Project. Located near the mouth of the river's canyon upstream from the confluence of the Gila with Mogollon Creek and below Turkey Creek, the dam was to be part of the CAP's Gila River Division, authorized under the 1968 Colorado River Basin Project Act. The project was planned to provide 18,000 acre feet (0.022 km3)/year of water to western New Mexico.

The Big Creek Hydroelectric Project is an extensive hydroelectric power scheme on the upper San Joaquin River system, in the Sierra Nevada of central California. The project is owned and operated by Southern California Edison (SCE). The use and reuse of the waters of the San Joaquin River, its South Fork, and the namesake of the project, Big Creek – over a vertical drop of 6,200 ft (1,900 m) – have over the years inspired a nickname, "The Hardest Working Water in the World".