Related Research Articles

Rousay is a small, hilly island about 3 km (1.9 mi) north of Mainland, the largest island in the Orkney Islands of Scotland. It has been nicknamed "Egypt of the north", due to its archaeological diversity and importance.

A trow is a malignant or mischievous fairy or spirit in the folkloric traditions of the Orkney and Shetland islands. Trows may be regarded as monstrous giants at times, or quite the opposite, short-statured fairies dressed in grey.

A kelpie, or water kelpie, is a shape-shifting spirit inhabiting lochs in Irish and Scottish folklore. It is usually described as a grey or white horse-like creature, able to adopt human form. Some accounts state that the kelpie retains its hooves when appearing as a human, leading to its association with the Christian idea of Satan as alluded to by Robert Burns in his 1786 poem "Address to the Devil".

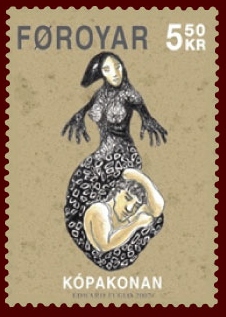

Selkies are mythological creatures that can shapeshift between seal and human forms by removing or putting on their seal skin. They feature prominently in the oral traditions and mythology of various cultures, especially those of Celtic and Norse origin. The term “selkie” derives from the Scots word for “seal”, and is also spelled as silkies, sylkies, or selchies. Selkies are sometimes referred to as selkie folk, meaning 'seal folk'. Selkies are mainly associated with the Northern Isles of Scotland, where they are said to live as seals in the sea but shed their skin to become human on land.

The nuckelavee or nuckalavee is a horse-like demon from Orcadian folklore that combines equine and human elements. British folklorist Katharine Briggs called it "the nastiest" of all the demons of Scotland's Northern Isles. The nuckelavee's breath was thought to wilt crops and sicken livestock, and the creature was held responsible for droughts and epidemics on land despite being predominantly a sea-dweller.

The each-uisge is a water spirit in Irish and Scottish folklore, spelled as the each-uisce in Ireland and cabbyl-ushtey on the Isle of Man. It usually takes the form of a horse, and is similar to the kelpie but far more vicious.

The wulver or wullver is a kind of wolf-like humanoid creature in the folklore of the Shetland Islands of Scotland. In modern times, the origin of the wulver has been disputed.

Glashtyn is a legendary creature from Manx folklore.

The Linton Worm is a mythical beast referred to in a Scottish Borders legend dating back to the 12th century. "Wyrm" is the Old Norse for serpent. A 12th-century writer believed it to be "In length three Scots yards and bigger than an ordinary man’s leg – in form and callour to our common muir edders." The myth is similar to that of the more famous Lambton Worm.

A tangie is a shape-shifting sea spirit in the folklore of the Orkney and Shetland Islands in Scotland. A sea horse or merman, it takes on the appearance of either a horse or an aged man. Usually described as being covered with seaweed, its name derives from "tang" or seaweed of the genus Fucus.

A water horse is a mythical creature, such as the Ceffyl Dŵr, Capaill Uisce, the bäckahäst and kelpie.

William Alexander Clouston was a Scottish 19th century folklorist from Orkney.

A water spirit is a kind of supernatural being found in the folklore of many cultures:

Muckle Water is a long, narrow fresh water loch on Ward Hill on Rousay, Orkney, Scotland. It is the biggest loch on the island and is popular for fishing. It can be reached by a track from the roadside. The Suso Burn on the north eastern shore drains the loch into the Sound of Rousay.

The water bull, also known as tarbh-uisge in Scottish Gaelic, is a mythological Scottish creature similar to the Manx tarroo ushtey. Generally regarded as a nocturnal resident of moorland lochs, it is usually more amiable than its equine counterpart the water horse, but has similar amphibious and shapeshifting abilities.

Sea Mither, or Mither of the Sea, is a mythical being of Orcadian folklore that lives in the sea during summer, when she confines the demonic nuckelavee to the ocean depths. Each spring she battles with her arch-enemy Teran, another spirit of Orcadian legend capable of causing severe winter storms, to gain control of the seas and the weather. Eventually Sea Mither overcomes Teran and sends him to the depths of the ocean, but the effort of keeping him confined there along with her other benevolent labours during the summer exhaust her, until in the autumn Teran takes advantage of her weakness to wrest control from her once again.

The stoor worm, or Mester Stoor Worm, was a gigantic evil sea serpent of Orcadian folklore, capable of contaminating plants and destroying animals and humans with its putrid breath. It is probably an Orkney variant of the Norse Jörmungandr, also known as the Midgard Serpent, or world serpent, and has been described as a sea dragon.

Assipattle and the Stoor Worm is an Orcadian folktale relating the battle between the eponymous hero and a gigantic sea serpent known as the stoor worm. The tale was preserved by 19th-century antiquarian Walter Traill Dennison, and retold by another Orcadian folklorist, Ernest Marwick, in a 20th-century version that integrates Dennison's texts with tidbits from other oral storytellers.

Jessie Margaret Edmondston Saxby was a writer and folklorist from Unst, one of the Shetland Islands of Scotland. She also had political interests and was a suffragette.

Witchcraft in Orkney possibly has its roots in the settlement of Norsemen on the archipelago from the eighth century onwards. Until the early modern period magical powers were accepted as part of the general lifestyle, but witch-hunts began on the mainland of Scotland in about 1550, and the Scottish Witchcraft Act of 1563 made witchcraft or consultation with witches a crime punishable by death. One of the first Orcadians tried and executed for witchcraft was Allison Balfour, in 1594. Balfour, her elderly husband and two young children, were subjected to severe torture for two days to elicit a confession from her.

References

Notes

- ↑ Finns in Shetland lore were distinct from the Finfolk of Orkney described by Walter Traill Dennison; [22] Finns later coalesced with supernatural marine entities, as which they are better known. [3]

Citations

- ↑ Barnes (1984), p. 352

- ↑ Barnes (1984), p. 355

- 1 2 3 Dr. Andrew Jennings (2010), "The Finnfolk", University of the Highlands and Islands, archived from the original on 23 October 2014, retrieved 13 June 2016

- ↑ Briggs (2002), p. 108

- ↑ "neugle, n", Dictionary of the Scots Language (online ed.), retrieved 13 June 2016

- ↑ "shoupiltin, n", Dictionary of the Scots Language (online ed.), retrieved 13 June 2016

- ↑ Edmondston (1866), pp. 77, 101

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Marwick (2000), p. 23

- 1 2 Blind (1881), p. 191

- 1 2 3 Teit (1918), p. 183

- ↑ Abrams (2005), p. 35

- 1 2 3 4 Blind (1881), p. 189

- ↑ "The Nuggle", Orkneyjar, archived from the original on 3 March 2016, retrieved 22 June 2016

- ↑ "Fishing and watersports", Discover Rousay, archived from the original on 4 March 2016, retrieved 22 June 2016

- ↑ Bruford (1997), p. 131

- 1 2 Saxby (1932), p. 141

- ↑ Bruford (1997), p. 123

- ↑ Angus (1914), p. 96

- ↑ MacKillop, James (2004). "Each uisce" . each uisce, each uisge, aughisky (online ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-860967-4 . Retrieved 13 June 2016.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 Saxby (1932), p. 140

- 1 2 3 4 5 Teit (1918), p. 184

- ↑ Marwick (2000), p. 25

- ↑ Spence (1899), p. 23

- ↑ Peacock (1900), p. 316

- ↑ Spence (1899), pp. 7–8

- ↑ Teit (1918), p. 186

Bibliography

- Abrams, Lynn (2005), Myth and Materiality in a Woman's World: Shetland 1800-2000, Manchester University Press, ISBN 978-0-7190-6592-7

- Angus, James Stout (1914), A Glossary of the Shetland Dialect, Alexander Gardner

- Barnes, Michael P. (1984), "Orkney and Shetland Norn", in Trudgill, Peter (ed.), Language in the British Isles, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-28409-7

- Blind, Karl (1881), "Scottish, Shetlandic and Germanic Water Tales", The Contemporary Review , XL, Strahan

- Briggs, Katharine Mary (2002) [1967], The Fairies in Tradition and Literature, Psychology Press, ISBN 978-0-415-28601-5

- Bruford, Alan (1997), "Trolls, Hillfolks, Finns and Picts", in Narvez, Peter (ed.), The Good People: New Fairylore Essays, University Press of Kentucky, ISBN 0-8131-0939-6

- Edmondston, Thomas (1866), An Etymological Glossary of the Shetland and Orkney Dialect, Asher

- Marwick, Ernest W. (2000) [1975], The Folklore of Orkney and Shetland, Birlinn, ISBN 978-1-84158-048-7

- Peacock, Florence (September 1900), "Review", Folklore, 11 (3), Folklore Society, JSTOR 1253125

- Saxby, Jessie M. E. (1932), Shetland Traditional Lore, Grant & Murray

- Spence, John (1899), Shetland Folk-lore, Johnson and Greig

- Teit, J. A. (April–June 1918), "Water-Beings in Shetlandic Folk-Lore, as Remembered by Shetlanders in British Columbia", The Journal of American Folklore, 31 (120), American Folklore Society: 180–201, doi:10.2307/534874, JSTOR 534874