An octopus is a soft-bodied, eight-limbed mollusc of the order Octopoda. The order consists of some 300 species and is grouped within the class Cephalopoda with squids, cuttlefish, and nautiloids. Like other cephalopods, an octopus is bilaterally symmetric with two eyes and a beaked mouth at the center point of the eight limbs. The soft body can radically alter its shape, enabling octopuses to squeeze through small gaps. They trail their eight appendages behind them as they swim. The siphon is used both for respiration and for locomotion, by expelling a jet of water. Octopuses have a complex nervous system and excellent sight, and are among the most intelligent and behaviourally diverse of all invertebrates.

A cephalopod is any member of the molluscan class Cephalopoda such as a squid, octopus, cuttlefish, or nautilus. These exclusively marine animals are characterized by bilateral body symmetry, a prominent head, and a set of arms or tentacles modified from the primitive molluscan foot. Fishers sometimes call cephalopods "inkfish", referring to their common ability to squirt ink. The study of cephalopods is a branch of malacology known as teuthology.

Sentience is the simplest or most primitive form of cognition, consisting of a conscious awareness of stimuli without association or interpretation. The word was first coined by philosophers in the 1630s for the concept of an ability to feel, derived from Latin sentiens (feeling), to distinguish it from the ability to think (reason).

Chromatophores are cells that produce color, of which many types are pigment-containing cells, or groups of cells, found in a wide range of animals including amphibians, fish, reptiles, crustaceans and cephalopods. Mammals and birds, in contrast, have a class of cells called melanocytes for coloration.

Cephalization is an evolutionary trend in animals that, over many generations, the special sense organs and nerve ganglia become concentrated towards the rostral end of the body where the mouth is located, often producing an enlarged head. This is associated with the animal's movement direction and bilateral symmetry, and cephalization of the nervous system led to the formation of a functional centralized brain in three groups of bilaterian animals, namely the arthropods, cephalopod molluscs, and vertebrates (craniates).

Cephalopod intelligence is a measure of the cognitive ability of the cephalopod class of molluscs.

Animal consciousness, or animal awareness, is the quality or state of self-awareness within an animal, or of being aware of an external object or something within itself. In humans, consciousness has been defined as: sentience, awareness, subjectivity, qualia, the ability to experience or to feel, wakefulness, having a sense of selfhood, and the executive control system of the mind. Despite the difficulty in definition, many philosophers believe there is a broadly shared underlying intuition about what consciousness is.

All cephalopods possess flexible limbs extending from their heads and surrounding their beaks. These appendages, which function as muscular hydrostats, have been variously termed arms, legs or tentacles.

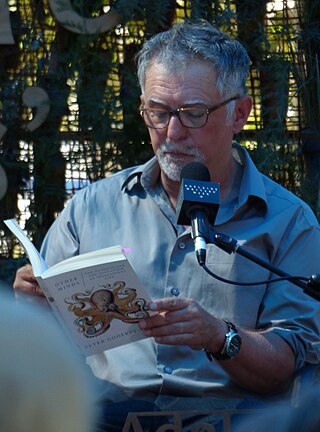

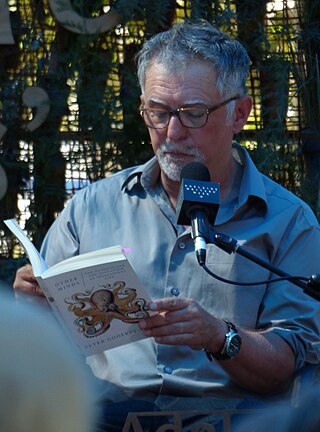

Peter Godfrey-Smith is an Australian philosopher of science and writer, who is currently Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Sydney. He works primarily in philosophy of biology and philosophy of mind, and also has interests in general philosophy of science, pragmatism, and some parts of metaphysics and epistemology. Godfrey-Smith was elected to the American Philosophical Society in 2022.

Cephalopod ink is a dark-coloured or luminous ink released into water by most species of cephalopod, usually as an escape mechanism. All cephalopods, with the exception of the Nautilidae and the Cirrina, are able to release ink to confuse predators.

Cuttlefish, or cuttles, are marine molluscs of the order Sepiida. They belong to the class Cephalopoda which also includes squid, octopuses, and nautiluses. Cuttlefish have a unique internal shell, the cuttlebone, which is used for control of buoyancy.

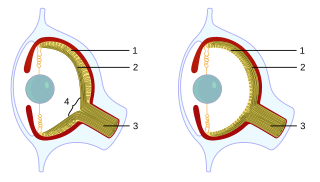

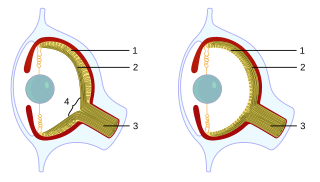

Cephalopods, as active marine predators, possess sensory organs specialized for use in aquatic conditions. They have a camera-type eye which consists of an iris, a circular lens, vitreous cavity, pigment cells, and photoreceptor cells that translate light from the light-sensitive retina into nerve signals which travel along the optic nerve to the brain. For the past 140 years, the camera-type cephalopod eye has been compared with the vertebrate eye as an example of convergent evolution, where both types of organisms have independently evolved the camera-eye trait and both share similar functionality. Contention exists on whether this is truly convergent evolution or parallel evolution. Unlike the vertebrate camera eye, the cephalopods' form as invaginations of the body surface, and consequently the cornea lies over the top of the eye as opposed to being a structural part of the eye. Unlike the vertebrate eye, a cephalopod eye is focused through movement, much like the lens of a camera or telescope, rather than changing shape as the lens in the human eye does. The eye is approximately spherical, as is the lens, which is fully internal.

Underwater camouflage is the set of methods of achieving crypsis—avoidance of observation—that allows otherwise visible aquatic organisms to remain unnoticed by other organisms such as predators or prey.

Deimatic behaviour or startle display means any pattern of bluffing behaviour in an animal that lacks strong defences, such as suddenly displaying conspicuous eyespots, to scare off or momentarily distract a predator, thus giving the prey animal an opportunity to escape. The term deimatic or dymantic originates from the Greek δειματόω (deimatóo), meaning "to frighten".

Cephalopods, usually specifically octopuses, squids, nautiluses and cuttlefishes, are most commonly represented in popular culture in the Western world as creatures that spray ink and use their tentacles to persistently grasp at and hold onto objects or living creatures.

Pain in cephalopods is a contentious issue. Pain is a complex mental state, with a distinct perceptual quality but also associated with suffering, which is an emotional state. Because of this complexity, the presence of pain in non-human animals, or another human for that matter, cannot be determined unambiguously using observational methods, but the conclusion that animals experience pain is often inferred on the basis of likely presence of phenomenal consciousness which is deduced from comparative brain physiology as well as physical and behavioural reactions.

The dwarf cuttlefish (Sepia bandensis), also known as the stumpy-spined cuttlefish, is a species of cuttlefish native to the shallow coastal waters of the Central Indo-Pacific. The holotype of the species was collected from Banda Neira, Indonesia. It is common in coral reef and sandy coast habitats, usually in association with sea cucumbers and sea stars. Sepia baxteri and Sepia bartletti are possible synonyms.

Octopolis and Octlantis are two non-human settlements occupied by gloomy octopuses in Jervis Bay, on the south coast of New South Wales. The first site, named "Octopolis" by biologists, was found in 2009. Octopolis consists of a bed of shells in an ellipse shape, 2–3 meters diameter on its longer axis, with a single piece of anthropogenic detritus, believed to be scrap metal, within the site. Octopuses build dens by burrowing into the shell bed. The shells appear to provide a much better building material for the octopuses than the fine sediment around the site. Up to 14 octopuses have been seen at Octopolis at a single time. In 2016, a second settlement was found nearby, named "Octlantis," which includes no human-made objects and can house similar numbers of octopuses. Both sites are within Booderee National Park. Some media accounts have described these sites as octopus "cities," but researchers who have worked on the sites view this as a misleading analogy.

Octopus bocki is a species of octopus, which has been located near south Pacific islands such as Fiji, the Philippines, and Moorea and can be found hiding in coral rubble. They can also be referred to as the Bock's pygmy octopus. They are nocturnal and use camouflage as their primary defense against predators as well as to ambush their prey. Their typical prey are crustaceans, crabs, shrimp, and small fish and they can grow to be up to 10cm in size.