A wetland is a distinct ecosystem that is flooded or saturated by water, either permanently for years or decades or seasonally for a shorter periods. Flooding results in oxygen-poor (anoxic) processes taking place, especially in the soils. Wetlands are different from other land forms or water bodies due to their aquatic plants adapted to oxygen-poor waterlogged soils. Wetlands are considered among the most biologically diverse of all ecosystems, serving as home to a wide range of plant and animal species. Methods exist for assessing wetland functions and wetland ecological health. These methods have contributed to wetland conservation by raising public awareness of the functions that wetlands can provide. Constructed wetlands are a type of wetland that can treat wastewater and stormwater runoff. They may also play a role in water-sensitive urban design. Environmental degradation threatens wetlands more than any other ecosystem on Earth, according to the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment from 2005.

A fen is a type of peat-accumulating wetland fed by mineral-rich ground or surface water. It is one of the main types of wetlands along with marshes, swamps, and bogs. Bogs and fens, both peat-forming ecosystems, are also known as mires. The unique water chemistry of fens is a result of the ground or surface water input. Typically, this input results in higher mineral concentrations and a more basic pH than found in bogs. As peat accumulates in a fen, groundwater input can be reduced or cut off, making the fen ombrotrophic rather than minerotrophic. In this way, fens can become more acidic and transition to bogs over time.

A bog or bogland is a wetland that accumulates peat as a deposit of dead plant materials – often mosses, typically sphagnum moss. It is one of the four main types of wetlands. Other names for bogs include mire, mosses, quagmire, and muskeg; alkaline mires are called fens. A bayhead is another type of bog found in the forest of the Gulf Coast states in the United States. They are often covered in heath or heather shrubs rooted in the sphagnum moss and peat. The gradual accumulation of decayed plant material in a bog functions as a carbon sink.

In ecology, a marsh is a wetland that is dominated by herbaceous plants rather than by woody plants. More in general, the word can be used for any low-lying and seasonally waterlogged terrain. In Europe and in agricultural literature low-lying meadows that require draining and embanked polderlands are also referred to as marshes or marshland.

Sphagnum is a genus of approximately 380 accepted species of mosses, commonly known as sphagnum moss, also bog moss and quacker moss. Accumulations of Sphagnum can store water, since both living and dead plants can hold large quantities of water inside their cells; plants may hold 16 to 26 times as much water as their dry weight, depending on the species. The empty cells help retain water in drier conditions.

Peat swamp forests are tropical moist forests where waterlogged soil prevents dead leaves and wood from fully decomposing. Over time, this creates a thick layer of acidic peat. Large areas of these forests are being logged at high rates.

Carbon sequestration is the process of storing carbon in a carbon pool. It plays a crucial role in limiting climate change by reducing the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. There are two main types of carbon sequestration: biologic and geologic. Biologic carbon sequestration is a naturally occurring process as part of the carbon cycle. Humans can enhance it through deliberate actions and use of technology. Carbon dioxide is naturally captured from the atmosphere through biological, chemical, and physical processes. These processes can be accelerated for example through changes in land use and agricultural practices, called carbon farming. Artificial processes have also been devised to produce similar effects. This approach is called carbon capture and storage. It involves using technology to capture and sequester (store) CO

2 that is produced from human activities underground or under the sea bed.

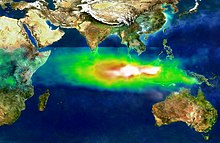

The Borneo peat swamp forests ecoregion, within the tropical and subtropical moist broadleaf forests biome, are on the island of Borneo, which is divided between Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia.

Blanket bog or blanket mire, also known as featherbed bog, is an area of peatland, forming where there is a climate of high rainfall and a low level of evapotranspiration, allowing peat to develop not only in wet hollows but over large expanses of undulating ground. The blanketing of the ground with a variable depth of peat gives the habitat type its name. Blanket bogs are found extensively throughout the northern hemisphere - well-studied examples are found in Ireland and Scotland, but vast areas of North American tundra also qualify as blanket bogs. In Europe, the southernmost edge of range of this habitat has been recently mapped in the Cantabrian Mountains, northern Spain, but the current distribution of blanket bogs globally remains unknown.

Ombrotrophic ("cloud-fed"), from Ancient Greek ὄμβρος (ómvros) meaning "rain" and τροφή (trofí) meaning "food"), refers to soils or vegetation which receive all of their water and nutrients from precipitation, rather than from streams or springs. Such environments are hydrologically isolated from the surrounding landscape, and since rain is acidic and very low in nutrients, they are home to organisms tolerant of acidic, low-nutrient environments. The vegetation of ombrotrophic peatlands is often bog, dominated by Sphagnum mosses. The hydrology of these environments are directly related to their climate, as precipitation is the water and nutrient source, and temperatures dictate how quickly water evaporates from these systems.

Palsas are peat mounds with a permanently frozen peat and mineral soil core. They are a typical phenomenon in the polar and subpolar zone of discontinuous permafrost. One of their characteristics is having steep slopes that rise above the mire surface. This leads to the accumulation of large amounts of snow around them. The summits of the palsas are free of snow even in winter, because the wind carries the snow and deposits on the slopes and elsewhere on the flat mire surface. Palsas can be up to 150 m in diameter and can reach a height of 12 m.

Tropical peat is a type of histosol that is found in tropical latitudes, including South East Asia, Africa, and Central and South America. Tropical peat mostly consists of dead organic matter from trees instead of spaghnum which are commonly found in temperate peat. This soils usually contain high organic matter content, exceeding 75% with dry low bulk density around 0.2 mg/m3 (0.0 gr/cu ft).

Aulacomnium palustre, the bog groove-moss or ribbed bog moss, is a moss that is nearly cosmopolitan in distribution. It occurs in North America, Hispaniola, Venezuela, Eurasia, and New Zealand. In North America, it occurs across southern arctic, subboreal, and boreal regions from Alaska and British Columbia to Greenland and Quebec. Documentation of ribbed bog moss's distribution in the contiguous United States is probably incomplete. It is reported sporadically south to Washington, Wyoming, Georgia, and Virginia.

Arctic methane release is the release of methane from Arctic ocean waters as well as from soils in permafrost regions of the Arctic. While it is a long-term natural process, methane release is exacerbated by global warming. This results in a positive climate change feedback, as methane is a powerful greenhouse gas. The Arctic region is one of many natural sources of methane. Climate change could accelerate methane release in the Arctic, due to the release of methane from existing stores, and from methanogenesis in rotting biomass. When permafrost thaws as a consequence of warming, large amounts of organic material can become available for methanogenesis and may ultimately be released as methane.

The permafrost carbon cycle or Arctic carbon cycle is a sub-cycle of the larger global carbon cycle. Permafrost is defined as subsurface material that remains below 0o C for at least two consecutive years. Because permafrost soils remain frozen for long periods of time, they store large amounts of carbon and other nutrients within their frozen framework during that time. Permafrost represents a large carbon reservoir, one which was often neglected in the initial research determining global terrestrial carbon reservoirs. Since the start of the 2000s, however, far more attention has been paid to the subject, with an enormous growth both in general attention and in the scientific research output.

Greenhouse gas emissions from wetlands of concern consist primarily of methane and nitrous oxide emissions. Wetlands are the largest natural source of atmospheric methane in the world, and are therefore a major area of concern with respect to climate change. Wetlands account for approximately 20–30% of atmospheric methane through emissions from soils and plants, and contribute an approximate average of 161 Tg of methane to the atmosphere per year.

A peatland is a type of wetland whose soils consist of organic matter from decaying plants, forming layers of peat. Peatlands arise because of incomplete decomposition of organic matter, usually litter from vegetation, due to water-logging and subsequent anoxia. Like coral reefs, peatlands are unusual landforms that derive mostly from biological rather than physical processes, and can take on characteristic shapes and surface patterning.

Paludiculture is wet agriculture and forestry on peatlands. Paludiculture combines the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions from drained peatlands through rewetting with continued land use and biomass production under wet conditions. “Paludi” comes from the Latin “palus” meaning “swamp, morass” and "paludiculture" as a concept was developed at Greifswald University. Paludiculture is a sustainable alternative to drainage-based agriculture, intended to maintain carbon storage in peatlands. This differentiates paludiculture from agriculture like rice paddies, which involve draining, and therefore degrading wetlands.

Jill L. Bubier is a professor emerita of environmental science at Mount Holyoke College (MHC). Her research examines how Northern ecosystems respond to climate change.

Peatland restoration is a term describing measures to restore the original form and function of peatlands, or wet peat-rich areas. This landscape globally occupies 400 million hectares or 3% of land surface on Earth. Historically, peatlands have been drained for several main reasons; peat extraction, creation of agricultural land, and forestry usage. However, this activity has caused degradation affecting this landscape's structure through damage to habitats, hydrology, nutrients cycle, carbon balance and more.