Related Research Articles

Penectomy is penis removal through surgery, generally for medical or personal reasons.

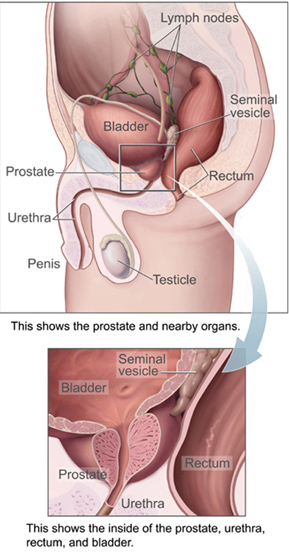

The prostate is both an accessory gland of the male reproductive system and a muscle-driven mechanical switch between urination and ejaculation. It is found in all male mammals. It differs between species anatomically, chemically, and physiologically. Anatomically, the prostate is found below the bladder, with the urethra passing through it. It is described in gross anatomy as consisting of lobes and in microanatomy by zone. It is surrounded by an elastic, fibromuscular capsule and contains glandular tissue, as well as connective tissue.

Genital modifications are forms of body modifications applied to the human sexual organs, such as piercings, circumcision, or labiaplasty.

Castration is any action, surgical, chemical, or otherwise, by which a male loses use of the testicles: the male gonad. Surgical castration is bilateral orchiectomy, while chemical castration uses pharmaceutical drugs to deactivate the testes. Castration causes sterilization ; it also greatly reduces the production of hormones, such as testosterone and estrogen. Surgical castration in animals is often called neutering.

Prostate cancer is the uncontrolled growth of cells in the prostate, a gland in the male reproductive system below the bladder. Early prostate cancer causes no symptoms. Abnormal growth of prostate tissue is usually detected through screening tests, typically blood tests that check for prostate-specific antigen (PSA) levels. Those with high levels of PSA in their blood are at increased risk for developing prostate cancer. Diagnosis requires a biopsy of the prostate. If cancer is present, the pathologist assigns a Gleason score, and a higher score represents a more dangerous tumor. Medical imaging is performed to look for cancer that has spread outside the prostate. Based on the Gleason score, PSA levels, and imaging results, a cancer case is assigned a stage 1 to 4. Higher stage signifies a more advanced, more dangerous disease.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), also called prostate enlargement, is a noncancerous increase in size of the prostate gland. Symptoms may include frequent urination, trouble starting to urinate, weak stream, inability to urinate, or loss of bladder control. Complications can include urinary tract infections, bladder stones, and chronic kidney problems.

Penile cancer, or penile carcinoma, is a cancer that develops in the skin or tissues of the penis. Symptoms may include abnormal growth, an ulcer or sore on the skin of the penis, and bleeding or foul smelling discharge.

Phalloplasty is the construction or reconstruction of a penis or the artificial modification of the penis by surgery. The term is also occasionally used to refer to penis enlargement.

Gender-affirming surgery for female-to-male transgender people includes a variety of surgical procedures that alter anatomical traits to provide physical traits more comfortable to the trans man's male identity and functioning.

Genital reconstructive surgery may refer to:

Emasculation is the removal of both the penis and the scrotum, the external male sex organs. It differs from castration, which is the removal of the testicles only, although the terms are sometimes used interchangeably. The potential medical consequences of emasculation are more extensive than those associated with castration, as the removal of the penis gives rise to a unique series of complications. There are a range of religious, cultural, punitive, and personal reasons why someone may choose to emasculate themselves or another person.

Scrotoplasty, also known as oscheoplasty, is a type of surgery to create or repair the scrotum. The history of male genital plastic surgery is rooted in many cultures and dates back to ancient times. However, scientific research for male genital plastic surgery such as scrotoplasty began to develop in the early 1900s. The development of testicular implants began in 1940 made from materials outside of what is used today. Today, testicular implants are created from saline or gel filled silicone rubber. There are a variety of reasons why scrotoplasty is done. Some transgender men and intersex or non-binary people who were assigned female at birth may choose to have this surgery to create a scrotum, as part of their transition. Other reasons for this procedure include addressing issues with the scrotum due to birth defects, aging, or medical conditions such as infection. For newborn males with penoscrotal defects such as webbed penis, a condition in which the penile shaft is attached to the scrotum, scrotoplasty can be performed to restore normal appearance and function. For older male adults, the scrotum may extend with age. Scrotoplasty or scrotal lift can be performed to remove the loose, excess skin. Scrotoplasty can also be performed for males who undergo infection, necrosis, traumatic injury of the scrotum.

Radical retropubic prostatectomy is a surgical procedure in which the prostate gland is removed through an incision in the abdomen. It is most often used to treat individuals who have early prostate cancer. Radical retropubic prostatectomy can be performed under general, spinal, or epidural anesthesia and requires blood transfusion less than one-fifth of the time. Radical retropubic prostatectomy is associated with complications such as urinary incontinence and impotence, but these outcomes are related to a combination of individual patient anatomy, surgical technique, and the experience and skill of the surgeon.

Vaginectomy is a surgery to remove all or part of the vagina. It is one form of treatment for individuals with vaginal cancer or rectal cancer that is used to remove tissue with cancerous cells. It can also be used in gender-affirming surgery. Some people born with a vagina who identify as trans men or as nonbinary may choose vaginectomy in conjunction with other surgeries to make the clitoris more penis-like (metoidioplasty), construct of a full-size penis (phalloplasty), or create a relatively smooth, featureless genital area.

Penis transplantation is a surgical transplant procedure in which a penis is transplanted to a patient. The penis may be an allograft from a human donor, or it may be grown artificially, though the latter has not yet been transplanted onto a human.

A penile implant is an implanted device intended for the treatment of erectile dysfunction, Peyronie's disease, ischemic priapism, deformity and any traumatic injury of the penis, and for phalloplasty or metoidioplasty, including in gender-affirming surgery. Men also opt for penile implants for aesthetic purposes. Men's satisfaction and sexual function is influenced by discomfort over genital size which leads to seek surgical and non-surgical solutions for penis alteration. Although there are many distinct types of implants, most fall into one of two categories: malleable and inflatable transplants.

In human anatomy, the penis is an external male sex organ that additionally serves as the urinary duct. The main parts are the root, body, the epithelium of the penis including the shaft skin, and the foreskin covering the glans. The body of the penis is made up of three columns of tissue: two corpora cavernosa on the dorsal side and corpus spongiosum between them on the ventral side. The human male urethra passes through the prostate gland, where it is joined by the ejaculatory duct, and then through the penis. The urethra traverses the corpus spongiosum, and its opening, the meatus, lies on the tip of the glans. It is a passage both for urination and ejaculation of semen.

Treatment for prostate cancer may involve active surveillance, surgery, radiation therapy – including brachytherapy and external-beam radiation therapy, proton therapy, high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), cryosurgery, hormonal therapy, chemotherapy, or some combination. Treatments also extend to survivorship based interventions. These interventions are focused on five domains including: physical symptoms, psychological symptoms, surveillance, health promotion and care coordination. However, a published review has found only high levels of evidence for interventions that target physical and psychological symptom management and health promotion, with no reviews of interventions for either care coordination or surveillance. The favored treatment option depends on the stage of the disease, the Gleason score, and the PSA level. Other important factors include the man's age, his general health, and his feelings about potential treatments and their possible side-effects. Because all treatments can have significant side-effects, such as erectile dysfunction and urinary incontinence, treatment discussions often focus on balancing the goals of therapy with the risks of lifestyle alterations.

Gary J. Alter is an American plastic surgeon. His specialties include sex reassignment surgery, genital reconstruction surgery and facial feminization surgery. He appeared in two episodes of the reality television series, Dr. 90210. PRNewswire reported on June 5, 2015 that Dr. Gary J. Alter performed the body work plastic surgery on Caitlyn Jenner. He has a practice in Beverly Hills, CA.

References

- ↑ Loblaw, DA; Mendelson DS; Talcott JA; et al. (July 15, 2004). "American Society of Clinical Oncology recommendations for the initial hormonal management of androgen-sensitive metastatic, recurrent, or progressive prostate cancer". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 22 (14): 2927–41. doi:10.1200/JCO.2004.04.579. PMID 15184404. S2CID 20462746.

- ↑ Terris, Martha K; Audrey Rhee; et al. (August 1, 2006). "Prostate Cancer: Metastatic and Advanced Disease". eMedicine. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- ↑ Myers, Charles E (August 24, 2006). "Androgen Resistance, Part 1". Prostate Cancer Research Institute. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved January 11, 2007.

- ↑ Colapinto, John (December 11, 1997). "The True Story of John/Joan". Rolling Stone. pp. 54–97. Archived from the original on January 20, 2009. Retrieved February 22, 2010.

- ↑ Lalor, John Joseph (1882). Cyclopaedia of political science, political economy, and of the political history of the United States, Volume 1. Rand, McNally. p. 406. ISBN 9780598866110.

- ↑ Sommer, Matthew Harvey (2002). A Sex, Law, and Society in Late Imperial China. Stanford University Press. p. 33. ISBN 0804745595.

- ↑ Ibsch, Elrud & Fokkema, Douwe Wessel (2000). The conscience of humankind: literature and traumatic experiences. Rodopi. p. 176. ISBN 9042004207.

- ↑ Hodgson, Dorothy Louise (2001). Gendered modernities: ethnographic perspectives. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 250. ISBN 0312240139.

- ↑ Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. China Branch (1895). Journal of the China Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society for the year ..., Volumes 27–28. The Branch. p. 160.

- ↑ Gill, Robin D. (2007). The Woman Without a Hole – & Other Risky Themes from Old Japanese Poems (illustrated ed.). Paraverse Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0974261881.

- ↑ Gill, Robin D. (2007). Octopussy, Dry Kidney & Blue Spots – Dirty Themes from 18-19c Japanese Poems (illustrated ed.). Paraverse Press. p. 202. ISBN 978-0974261850.

- ↑ Constantine, P. (1994). Japanese Slang Uncensored. Tuttle Publishing. pp. 83, 164. ISBN 4900737038.

- ↑ Wood, Michael S. (2009). Literary Subjects Adrift: A Cultural History of Early Modern Japanese Castaway Narratives, Ca. 1780—1880. University of Oregon. p. 330. ISBN 978-1109119787.[ permanent dead link ]

- ↑ Moerman, D. Max (2009). "Demonology and Eroticism Islands of Women in the Japanese Buddhist Imagination" (PDF). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies. 36 (2). Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture: 351–380 (375). JSTOR 40660972. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 11, 2011. Retrieved November 11, 2012.

- ↑ Faure, Bernard (1998). The Red Thread: Buddhist Approaches to Sexuality (reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0691059977.

- ↑ Faure, Bernard (1998). The Red Thread: Buddhist Approaches to Sexuality (PDF) (reprint ed.). Princeton University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0691059977.

- ↑ Gill, Robin D. (2009). A Dolphin in the Woods: Composite Translation, Paraversing and Distilling Prose (illustrated ed.). Paraverse Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0984092314.

- ↑ Meaning of 宮刑 in Japanese. RomajiDesu Japanese dictionary

- ↑ 宮刑 – English translation. bab.la Japanese-English dictionary

- ↑ 宮刑 in English translated from Japanese Archived April 6, 2016, at the Wayback Machine . Vocing

- ↑ Japanese Vocabulary » 宮刑 on January 1, 2010 (January 1, 2010). "Japanese Vocabulary: 宮刑 » SayJack". Ja-jp.sayjack.com. Retrieved March 17, 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Definition for: 宮刑 [ permanent dead link ]. 2000 Kanji: A Japanese Dictionary

- ↑ 宮刑. Tangorin Japanese Dictionary

- ↑ Murray Gordon (1989). Slavery in the Arab World . Companions to Asian Studies. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 96. ISBN 9780941533300.

- ↑ HEALTH CARE IN CHINA-TRANSPLANTS AND DRUGS – China | Facts and Details

- 1 2 Conley, Mikaela (July 12, 2011). "Wife Chops Off Husband's Penis, Throws in Garbage Disposal". ABC news. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ "6 Things I Learned Having My Penis Surgically Removed". cracked.com. May 31, 2015.

- 1 2 Rettner, Rachael (July 13, 2011). "Man's Penis Cut Off By Wife: How Could Doctors Make a New One?". MyHealthNewsDaily. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Rettner, Rachael (July 13, 2011). "Man's Penis Cut Off By Wife: How Could Doctors Make a New One?". Live Science. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Maugh, Thomas H. II (July 15, 2011). "There are options for penis repair after mutilation". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved April 5, 2013.

- ↑ Pigot, Garry L.S.; Sigurjónsson, Hannes; Ronkes, Brechje; Al-Tamimi, Muhammed; van der Sluis, Wouter B. (January 2020). "Surgical Experience and Outcomes of Implantation of the ZSI 100 FtM Malleable Penile Implant in Transgender Men After Phalloplasty". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 17 (1): 152–158. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.09.019. PMID 31680006. S2CID 207890601.

- ↑ "SCIENCE WATCH; Sexual Organ Surgery". The New York Times. March 14, 1989. Retrieved April 5, 2013.